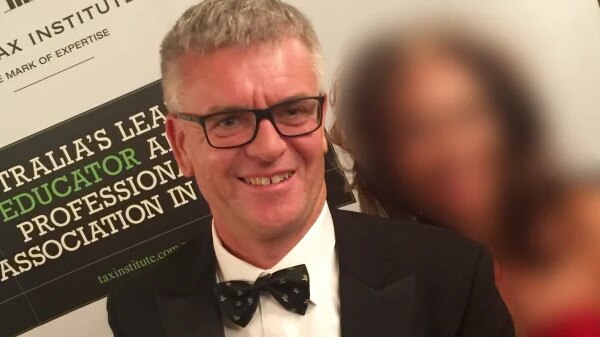

Stop outsourcing, says former EY partner Jim Birch

As PwC faces a significant dent in its government contracts, former EY partner Jim Birch says the government should curtail its outsourcing.

It’s a loud and clear wakeup call when in light of the PwC Australia tax leak scandal a former “big four” partner thinks the government needs to stop outsourcing so many big decisions to the big accounting firms.

That’s the view of non-executive director Jim Birch, a former EY partner and before that a senior public servant, who blames the skyrocketing use of consultants on a number of factors.

“The most significant is the progressive erosion of capability in the public sector over many years,” says Birch.

“Efficiency dividends, a reduction in executive overheads, the paucity of senior executive training and career paths, poor succession planning, has resulted in a loss of great capability.”

Until now perhaps, that loss has been a boon for highly paid consultants, some of whom charge $1300 per hour.

PwC alone earned $530m from the federal government in the past two years.

Now it turns out the firm was taking confidential information the government provided so it could advise on new international tax avoidance laws, and used that very same information to pitch its wares to high-fee paying companies on how to avoid paying tax.

As a result, the tide has turned so dramatically against the once-favoured firm that some politicians have called for it to be banned from bidding on government work again.

Accountancy author and former academic Adrian Raftery believes there will be staff losses at PwC as a result. Not from the firm cleaning out people with knowledge of the scandal – which it has failed to do – but from the good players who realise the brand damage will strip them of work.

“If I was the head of those other three big firms, I’d definitely be making a few extra phone calls,” says Dr Raftery.

“There is some great staff in there and it will be easy to say ‘you don’t want to be tarred with the same brush’ so I think it will be easy to entice not just partners but their whole staff.”

The rumour mill has certainly been running hot that EY has approached PwC’s Canberra consultants about a mass move across to the rival firm.

A spokeswoman from from EY denied these talks had occurred.

When Arthur Anderson lost its licence after shredding documents related to Enron, a new firm KordaMentha, was born of former staff who went out on their own.

To be sure, it’s unlikely PwC will fail as a result of this scandal, although a number of people at the top echelon of corporate Australia are staggered by how badly the firm has handled the unfurling disaster.

“It’s like a cancer spreading through the firm without therapy” is how one corporate adviser to multiple prime ministers has described the tax leak scandal

“They should be saying, what’s the worst that could come out? What is the most embarrassing and shameful material information that can be revealed? Let’s bring it out now. Let’s take the pain now and be proactive,” says the unnamed adviser.

“I’m just bewildered that PwC is still trying to hide it.”

The Australian Federal Police is now investigating former PwC partner Peter Collins and the actions of the firm.

Internal PwC emails, revealed in parliament as a result of the Tax Practitioners Board investigation, have shown 53 partners and staff from PwC were on messages where the scam was discussed.

Those emails are heavily redacted and only Collins’ name has been revealed despite calls, even from prime minister Anthony Albanese, for PwC to come clean about the names and the extent of the scandal.

The temperature will go up several notches this coming week when PwC fronts senate estimates.

Another senior business leader and former minister is shocked at how badly PwC is handling the crisis.

“I’d have sacked a lot of people, because that’s what is required,” says the former minister and business person, who has been involved in a significant corporate crisis.

“This is about survival. So in order to reset the firm, they’ve got to cut out anyone even who got an email because even if they got it and didn’t do anything about it, they still knew about it – so they can’t be part of the firm going forward.”

What comes next is trying to salvage the relationship with the government, by putting in place several probity advisers external to the firm who can manage these contracts and the confidentiality, giving government and the public some confidence that they understand the gravity of the problem, the former minister says.

In what health PwC survives will depend on what steps they take next, but Mr Birch believes whatever they do, the pool of fees for the “big four” firms will need to be less, going forward.

PwC led the pack in a tax avoidance scheme that the ATO this week said would have cost $180m per year if it had succeeded, and all the while the firm was earning hundreds of millions of dollars in taxpayer-funded fees for advice to the government.

Now the Canberra cash machine may be closing its doors – or at least trying to make them smaller – for the foreseeable future as the firm’s bad news continues to leak out.

“I cannot comment on PwC’s culture except to say that when trust is eroded then it is very difficult to maintain a positive and constructive business relationship,” Mr Birch says.

“This issue impacts far beyond PwC as the perception will be that all consultancy companies have this risk and, to be frank, that may not be the case.”

Regardless of risk and trust, Mr Birch believes governments need to get back to backing their own people and making their own decisions.

“It is very important that consultants are used only for very highly skilled requirements and also where it is clear that a major program of work is so large and complex that it requires some additional specialised skills,” he says. “Too often consultancies are providing employees as backfill for public sector staff gaps.”

The irony is the decision to cut back on consultants, might be one the government would have preferred to outsource as well.