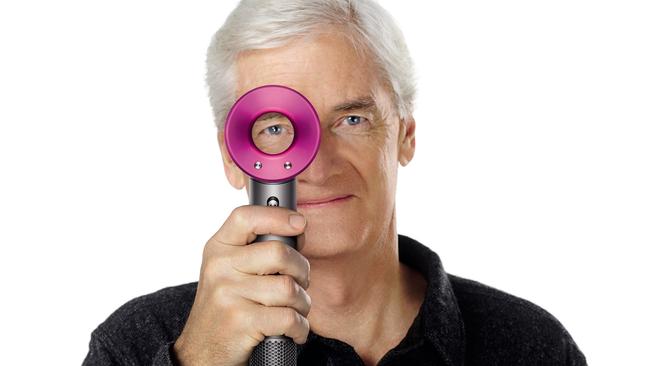

Sir James Dyson: the great reinventor

Sir James Dyson, notoriously secretive about his inventions, is poised to move into robotics, energy storage and artificial intelligence.

Sir James Dyson, inventor, iconoclast, billionaire, is in his light-filled Wiltshire office, the lean, spare limbs of the long-distance runner folded beneath him, feet encased in a pair of brightly coloured trainers. It is mid afternoon and outside, an army of bright young things from 54 different nations, most of them tech whizzes, engineers, scientists, and industrial designers, mill about and chatter in the sunshine.

The scene is reminiscent of a Silicon Valley start-up, rather buzzier and more youthful than the £5.4bn ($10.1bn) global engineering behemoth it is.

The graceful, long building we are in, designed by British architect Chris Wilkins, was originally Dyson’s first vacuum factory. Now, its distinctive wave-shaped roof houses the company’s research and development base, a £250m hatchery for new ideas and nerve centre for the construction and testing of prototypes – all of it conducted in military-style secrecy.

Dyson and his wife of 53 years, Deirdre, have only recently returned to live in England after spending two years in Singapore overseeing the stylish (if eye-wateringly expensive) refurb of the city-state’s historic St James power station, scheduled to be unveiled as the company’s new global headquarters next month. Southeast Asia is pivotal for Dyson: Australia was his first export market and Aussies his biggest fans, with one in three households equipped with a Dyson machine.

The company is unusual for Britain in that it remains entirely in family ownership. Since 1998, it has grown to employ more than 14,000 people around the globe, 6000 of them engineers and scientists. Dyson sold the 100 millionth appliance bearing his name in 2017, making him a very rich man, said to be worth more than £6bn, and seemingly, a very content one too.

At 74, he is blessed with the rude good health that allows continued creativity and long distance running, not to mention enjoyment of his three children and a brood of grandchildren.

Still, as we sit masked-up across the table to chat about his soon-to-be-released autobiography, Dyson bristles at times. A bubble of impatience sits politely beneath the cut glass English accent but is palpable, nevertheless.

His book, ‘‘Invention: A Life’’, was published on September 2 and is a great read, pacy, personal, and full of anecdotes about the great peaks and troughs that have defined his career. He reveals that he built more than 5,000 prototypes of the first bagless vacuum cleaner after being inspired by an industrial centrifugal dust extractor, experimenting with cardboard and sticky tape at home to see if the technology could be applied to a domestic appliance.

Endless invention

In his earliest years he designed the ‘‘Sea Truck’’, a high-speed boat used widely by the military for beach landings and later, a light and agile wheelbarrow with a ball in place of the traditional single wheel. A washing machine emerged from his psyche too, and while it worked brilliantly it turned out to be too complex to be profitable. Today, an army of designers and engineers continue to work on making every generation of his bagless vacuum cleaners lighter, more efficient and – let’s face it – prettier. His bladeless fans are now evolving into sophisticated air purification technology, batteries, deft and elegant lighting (the work of his son, Jake) and a line of hi-tech hair products.

More recently, he has also moved into farming, revealing an aesthetes’ passion for the restoration of traditional drystone walls and ancient hedgerows while experimenting with sustainable agricultural methods and cutting-edge technology. Not many Brits know it, but he is the country’s biggest producer of peas.

Still, I was surprised to read that despite his enormous success (he now owns more farming land than the Queen), Dyson has continued to encounter a continuing snobbishness in England about his engineering and manufacturing pathway: “It has become so powerful that there is some pride in not knowing anything about engineering. It’s the C.P. Snow analogy,” he adds, referring to the famous 1959 essay, ‘‘The Two Cultures’’ in which the great British scientist lamented the great cultural divide between science and the arts. “In my view it has got worse since. People don’t go into engineering partly because they think it’s difficult but more so because it’s frowned upon … there was a recent survey which showed engineers are regarded as being even below being a vicar in status,” he says and laughs when I add that journalists come even lower. What is even worse, he adds, is the notion that manufacturing is “dirty, a bit beneath the curve”.

“When I say at a cocktail party that I’m a manufacturer and not an engineer, people would turn away because they’re not interested and knew nothing about it. I used to do it deliberately and my wife would get very cross with me: ‘You’re doing that to provoke them’,” she’d say. Football is in their brains but not manufacturing.”

When I ask him if he thinks it’s societal, a peculiarly British class thing, he nods: “I think it’s [an attitude] true historically and probably still true today.”

Dyson’s book is, in some ways, more of an ode to failure than success, an exhortation to young people about taking risks, being resilient and picking yourself up off the floor when things go wrong and having the courage to commit, risk and jump in when things go right.

But it is also a love letter to his much loved, if much-maligned, discipline of engineering – even though Dyson himself is a graduate of the Royal Academy of Art and was trained in design, not in engineering.

“I’m an ordinary person. I didn’t even do science at school and yet here I am developing new technology. I don’t want young people to be put off by what their education has been, or what people have told them they are, because actually, they can do whatever they want to do, provided they are motivated,” he says.

“I have spent my life wishing more young people did engineering rather than going to media studies,” adding a ‘sorry’ with a laugh when he catches the look on my face. “Instead of talking about problems, I want young people to solve them. And they can. And they will. I wrote the book partly because of that and partly because the first students at our university will graduate this summer, in September … it’s a milestone for us and seeing how brilliantly they’ve done I thought it would be nice if people heard about the wonderful things they’ve done and are capable of.”

Dyson launched his Institute of Engineering and Technology when the Conservative MP and Universities’ Minister, Jo Johnson, brother of the British Prime Minister Boris, challenged the entrepreneur to do something himself about Britain’s shortage of engineers. The Institute is a gutsy experiment combining a traditional university’s academic rigour with hands-on and real-world experience working at Dyson. Students are paid a salary from day one, there are no tuition fees and in their first year, they all live in the spectacular Wilkins-designed accommodation pods that punctuate the Wiltshire site. At the end of their four-year degree, all students are offered a job with Dyson and the whole first crop of graduates have elected to stay on. Learning through doing, he says, defined his own life: “Unafraid to get your hands dirty to test something empirically to understand it properly,” he says.

Still, it hasn’t been an easy couple of years: in 2019, he was forced to shelve his dream of building a Dyson electric car after an elite team working in old World War II hangars up the road spent three years in secrecy and intensive research only to conclude they couldn’t compete with the big boys of the automotive industry. While major manufacturers like Toyota and VW can plough billions into the electric vehicle sphere, banking that economies of scale will ultimately pave the way for cheaper technology and decent returns, Dyson couldn’t find a way to make his beloved car price-competitive. He is sanguine about this ‘failure’ too, even though the exercise is reputed to have costed him £430m.

And early last year, as Covid-19 began to unleash its horrors in Europe, he marshalled his engineering resources to respond to an urgent British government request to build ventilators, only to be told a few weeks (and £20m) later they would not be needed after all.

Dyson’s car may not have materialised, but his tenacity is legendary and while he won’t say too much, the engineering team are said to have developed a car battery that offers greater range than its competitors, including Elon Musk’s Tesla. In November, he announced investment of more than £2.75bn in new technologies, including robotics and machine learning. This means that for the first time, consumers are likely to see new Dyson products outside the home.

Family values

Sir James grew up in Norfolk in the 1950s and was educated at the Gresham’s School where his father was Classics Master. Founded under the reign of Queen Mary I, the school has turned out many other highly individual and unorthodox young men, among them, the poet W.H Auden, composer Benjamin Britten, the notorious spy Donald McClean and Sir Martin Wood, inventor of the super magnets that led to MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) technology. Dyson says he took his foot off the academic pedal as a teenager, not because he was lazy but because he preferred any activity he could throw himself into bodily, from sports and long distance running to music and drama, playing the bassoon, acting, and set designing.

He remembers his cheerful polymath father with great longing, a man who loved hiking and sailing, ran the school hockey and rugby teams, wrote a children’s book illustrated with his own water colours and was blessed with a great sense of humour, including a penchant for inventing suggestive limericks.

His mother, the daughter of a vicar, was very young when she met her husband and missed out on university thanks to the war, but the couple were happy and quickly had three children, with James the youngest.

Dyson remembers ration books and being without adequate heating, growing their own vegetables and collecting precious eggs from the hens. It might have been a period of great austerity, but the three children grew up on the vast and empty beaches of Norfolk, free to explore nature, climb trees, build cubby houses, and dig exciting if dangerous sand tunnels.

Dyson was just eight years old when the family were returning from a holiday in Cornwall and his father stopped the car to be violently ill. He implored his young son not to tell his mother. Less than a year later, aged just 40, he died of throat and lung cancer, possibly related to his military service in Myanmar. This terrible loss, the move into boarding school aged nine and his mother’s extraordinary energy and determination to train as a teacher to keep the family afloat, he says, contributed to his own self-reliance and faith in pursuing his own ideas.

“My wife now claims that I have inherited my mother’s determination and warrior spirit. My mother did have high expectations. She was also very broad-minded and had a catholic choice of friends of all ages. Enjoying conversation on any subject, hers was a modern outlook. Ahead of her time, she was tolerant of others of all walks of life, happy to discuss anything,” he writes. “She coaxed me into seeing and understanding a broad culture. She encouraged my acting in plays, my playing the bassoon and painting, all things I had chosen to do myself.”

Dyson cites a long list of inventors, engineers and designers who inspired him in his earliest years, among them Sir Alec Issigonis, designer of the Mini Minor and Buckminster Fuller, the American futurist who designed the geodesic dome. He has long been a passionate art collector with a careful and refined eye and has always chosen headquarters and offices for their architectural bones, often restoring and repurposing with great taste and style.

He is, however, far less enthused by Britain’s political class, citing several disappointing and bruising encounters with politicians of both colours and persuasions (from Tony Blair to Theresa May) who all showed a surprising lack of interest in one of Britain’s greatest business success stories. And yet throughout the book, he is candid about describing failure after failure, from near bankruptcy and loss of the family house when the children were young to his decision to sue the US juggernaut Amway, for patent infringement. He has also spent millions on several legal battles to defend his business including against European Commission anti-competition practices – a case he ultimately won.

It is probably here that his well-known antipathy toward the EU was born and which fuelled his high-profile support for Brexit, sparking fury from the Remain-dominated British intellectual elite and earning him some remarkably hostile press coverage over the years. The decision to move the company’s headquarters from England to Singapore only solidified the enmity, unfairly, because he had made the decision some years before when he failed to gain planning permission to expand his factories in Wiltshire.

“We were producing 900,000 vacuum cleaners and we had run out of space so we applied for permission to build a factory behind those trees,” he says pointing out the window. “It was a beautiful building, and we were going to set it deeply into the ground so you couldn’t see it. Some locals got up in arms, particularly the hunting set led by a Conservative MP.” The project was referred to the Secretary of State – “the kiss of death” – and he ended up spending £1m and two years to push it through only to fail.

“They don’t like manufacturing,” he says of consecutive governments, his voice calm but belying a subterranean fury. “They don’t like us and don’t want it. They think it’s grubby and dirty, and demeaning for people working in factories. The only thing they like is that it creates jobs; they don’t think of it as wealth building, creating exports and foreign currency and promoting British prestige around the world. They don’t get that because they’ve never done it.”

Singapore beckoned instead, with incentives to take on unused factories, an environment that valued what he was doing, and an economic and political system that moved heaven and earth to help provide the labour, parts, space and flexibility he couldn’t find in Britain. The media, he says, chose to portray his move as an abandonment but the reality is that while 500 people were made redundant early on, thousands more have been employed in what is now his research and development hub. I spent a morning visiting his laboratories (no pictures allowed), which is unusual because he is notoriously careful about new products and doesn’t allow visitors, let alone media. Today, the company is making 30 million products each year.

Inpiration

Dyson says that his venture into education and his foundation, which funds an annual competition to encourage fledgling designers and inventors, are driven by the desire to show young people the excitement in pursuing a life of invention and discovery. The newest generation are full of brilliant ideas, he says, and their youth ensures they’re unafraid to pursue them, intent on finding cures for disease, harnessing what he calls ‘‘naive’’ thinking, untrammelled by tradition and expectation, to resolve even intractable problems. His own life, he says, has been defined by learning through doing, using a combination of the cerebral and practical.

“I really do enjoy making things and, whenever possible, doing things myself, constantly learning in the process. This is as true at work as it is at home and is evident from the various ‘projects’ we have bought as houses. At various points I have had to be a plumber, a plasterer, an electrician and, best of all, a JCB driver. I’ve designed new furniture and fittings.”

He has also spent more than £120m on philanthropic causes, from education to a new cancer wing at Bath Hospital where his children were born.

As a staffer enters his office, politely pointing out the time, I ask him about his passion for running and he tells me his inspiration began with the great Australian coach, Percy Cerruty, who trained Olympic champion Herb Elliott by running him up sandhills. As a youngster, Dyson promptly followed suit, running the great dunes around Norfolk. And he adds, almost as an aside, he designed his own running shoes: “I had to when I was at school because if you did cross-country, you wore what looked and felt like football boots. I got the cheapest pair of plimsolls you could buy – canvas with a thin rubber sole. I used a Stanley knife to cut ribs, channels across the soles to provide grip. They didn’t last very long but they were very light and very effective.”

I ask him to sketch just how he cut the soles and he draws me the simple design. Would that be the very first Dyson invention?

“Probably,” he laughs as he says goodbye.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout