‘Sins of omission’ sting Westpac

An investigation into catastrophic failures in Westpac’s anti-money laundering framework has blamed deficient processes and poor judgments.

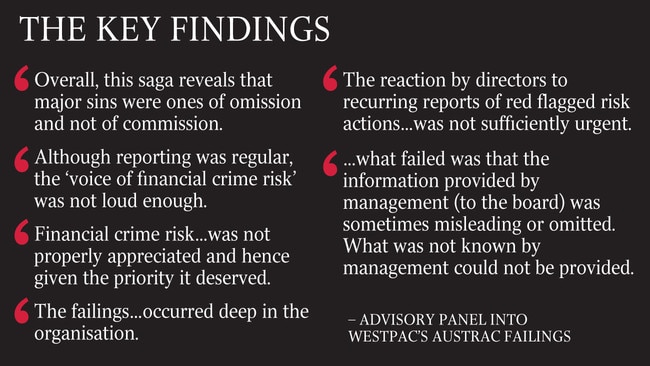

A top-level investigation into catastrophic failures in Westpac’s anti-money laundering framework has blamed “sins of omission and not of commission”, citing lack of accountability, deficient processes, poor individual judgments and a crowded board risk agenda.

The three-person advisory panel on board oversight found that directors arrived late at the scene, and could have recognised earlier the “systemic” nature of some of the financial crime issues.

However, reporting to the board on financial crime matters was at times “unintentionally incomplete and inaccurate”.

Westpac, as a result, would re-examine the lengthy 2018 self-assessment of its culture, governance and accountability to ensure the right lessons were learnt.

Chairman John McFarlane said this extra review was “pretty far advanced” and would be released in the September quarter.

“It’s been a very dark period for Westpac; sufficiently dark that we lost the chief executive (Brian Hartzer), the chairman (Lindsay Maxsted) and a senior director (Ewen Crouch),” Mr McFarlane told The Australian.

“We need to emerge back into the light, which can only be done when the Austrac matter is settled.”

Austrac up-ended Westpac’s management and board ranks last November when it lodged a Federal Court statement of claim alleging more than 23 million breaches of anti-money laundering and counterterrorist financing laws.

While Westpac made a series of key admissions in its May defence, the parties are still haggling over a penalty.

The bank has made a $900m provision, but the financial intelligence agency is believed to be seeking about $1.5bn — more than double the $700m penalty imposed on Commonwealth Bank for a range of similar breaches in 2017.

In the meantime, ASIC and the prudential regulator APRA have launched their own investigations into Westpac’s conduct.

The two reports released by the bank on Thursday included a management accountability review overseen by Promontory Financial Group, and a report on board governance by a three-person independent panel.

As foreshadowed by The Australian, there were no further management or board casualties.

However, an unspecified number of staff have left the bank, and others have suffered significant remuneration consequences and disciplinary action.

A range of 38 individuals have been penalised $13.2m in prior-year awards, including withheld short-term bonuses from 2019.

There has also been $6.9m worth of 2020 bonuses cancelled for the chief executive and group executives.

The management review, overseen by Promontory Financial Group, found three main causes of the debacle, with internal practices having notably improved since 2017.

It concluded that some areas of AML risk were “not sufficiently understood” by Westpac; accountabilities were unclear for managing compliance, and there was insufficient expertise and resourcing in the AML area.

Chief executive Peter King noted that the review looked back over 10 years, and appropriate action had been taken when fault was identified.

“Remuneration and disciplinary action took into consideration decisions already taken and announced, the level of direct managerial responsibility or accountability for the compliance failures, and the level of culpability for failings,” Mr King said.

“While the compliance failures were serious, the problems were faults of omission.

“There was no evidence of intentional wrongdoing.”

Mr McFarlane said Westpac’s remediation program focused on strengthening all aspects of non-financial risk management.

“We accept the recommendations of the advisory panel report and we are implementing them as part of the remediation plan, which is already well-advanced,” he said.

“We will have no tolerance for controllable negative events.

“Our transformation program was begun and will bring deep cultural change.”

The advisory panel, comprising Ziggy Switkowski, Kerry Schott and Colin Carter, blamed a “mix of technology and human error dating back to 2009” for Westpac’s failure to report 19.4 million international funds transfer instructions (IFTIs) to Austrac, including some transfers for 12 customers linked to possible child exploitation.

This was compounded by poor individual judgments and a lack of sufficient resourcing at the bank.

The report noted that, given the escalating focus on financial crime, directors could have identified some of the key issues earlier, but there was no deliberate action that led to the compliance problems.

“Austrac’s allegations against the bank include matters that were unknown at the time to the bank’s leadership,” it said.

“The failings — such as non-reported IFTIs or inadequate due diligence on correspondent banks and particular customers — occurred deep in the organisation and it is not reasonable to expect that a board should find these out.

“The board relies on information flows from management and it was the content of those flows that was poor.

“Information was (unintentionally) misleading and sometimes omitted.”

Directors, even so, were “not satisfactorily focused before 2017 and were slow off the mark” on financial crime matters, although this started to pick up after 2017.

“In the earlier years under review, it appears that the board and the board risk and compliance committee were slow to recognise global trends in financial crime and increased enforcement activity in AML/CTF,” the report said.

“The bank’s executive leadership and financial crime teams were light on relevant international experience — an undervalued competence — and specialist resources devoted to financial crime were insufficient.”

The reaction by Westpac’s directors to recurring reports of red-flagged risk actions in AML/CTF was also not sufficiently urgent.

A gap developed between board engagement with AML/CTF obligations and that which was expected by Austrac.

The panel limited its investigation to people inside the bank and former executives.

It interviewed both the former CEO Brian Hartzer and Mr King, as well as ex-chairman Lindsay Maxsted and other directors.

The business of banks, according to the panel, was no longer limited to the collection of deposits and lending. It also involved the accumulation, storage and monitoring of information on every transaction.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout