Sold by its South African owner to private equity, a new chapter in the venerable retailer has begun

David Jones has been sold to a private equity firm and is gearing up for Boxing Day sales that could reset its fortunes. We take a look back at the national retail treasure’s rise, fall and rise again.

David Jones was the type of department store the Queen would shop at.

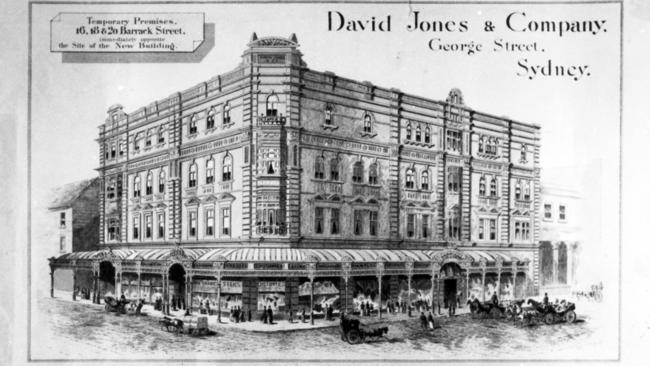

That was certainly what the owners of Australia’s only luxury department store must have hoped the public would believe in 1954 when the Queen became the first reigning British monarch to set foot on Australian soil and chose to step inside the flagship David Jones store at Sydney’s Elizabeth St.

Followed by the Duke of Edinburgh and adorned with a triple necklace of diamonds, matching chandelier earrings and a shimmering tiara, the Queen proceeded through the David Jones ground floor lavishly decorated with English Tudor roses, gladioli, dahlias and her iconic Royal Standard Lion Rampant flag.

The royal couple made their way to the famed David Jones Great Restaurant on the 7th floor – known as Seventh Heaven – where a state banquet was held in the Queen’s honour to mark the first social event of the royal tour. One newspaper breathlessly reported the David Jones royal spectacle as “superb loveliness”.

In a time before mass advertising, social media or events “going viral”, the message from that royal banquet 70 years ago was clear – this was the store of pomp and pageantry, of style and sophistication. It was the nation’s only luxury department store fit for royalty.

Its customers followed suit. Women would don their finest clothes – hats and gloves of course – to walk through David Jones. The opulence of the surroundings, the chandeliers, the piano player, imposing brass doors all made it a special rite of passage for discerning young women.

The grandeur and magnificence of David Jones was its hallmark as much as its marketing pitch to shoppers.

There was no pomp and pageantry, however, in 2019 when David Jones opened mini food stores inside BP petrol stations. There was instead model Rebecca Judd who gleefully posed for the cameras beside David Jones-branded rotisserie chickens, tinned tomatoes and smoked salmon. Within sight of the petrol pumps on a busy highway in a Melbourne bayside suburb, and next to a KFC outlet, David Jones executives tried to sell the idea that its well-heeled customers would walk past cans of Red Bull and meat pies to pick up a ready-made David Jones gourmet chicken spice rub after filling up with petrol. They didn’t. And within two years the disastrous idea spread across 35 service stations was killed off after losing millions.

String of disasters

It proved to be one of the last great gasps and failures for David Jones by its owners, South Africa’s Woolworths Holdings. Based in Johannesburg, Woolworths Holdings executives viewed the string of disasters at David Jones – many of their own making – with increasing alarm. Plans to dump the famous department store were already being hatched.

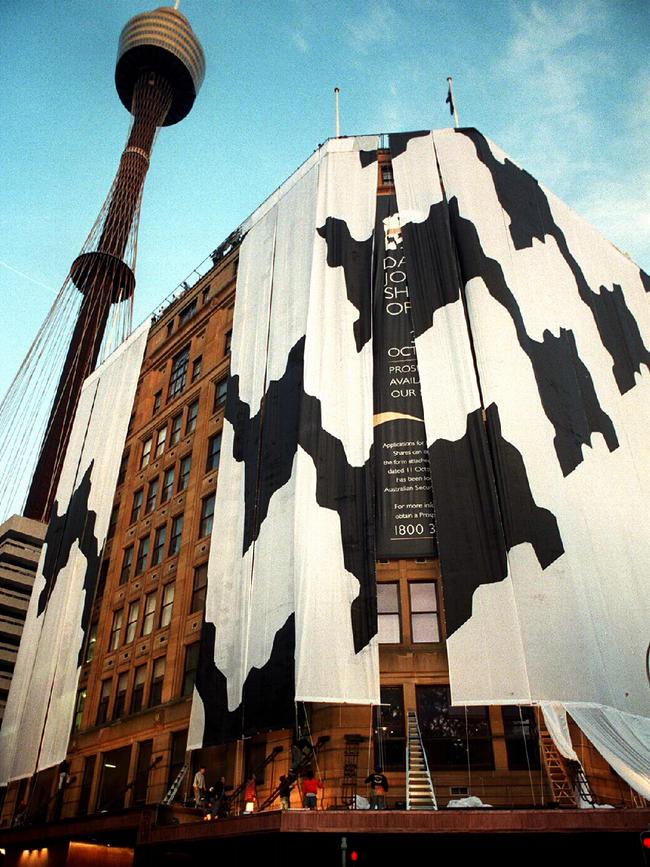

This week in a sign of sheer exasperation, exhaustion or just being utterly fed up, the 184-year old David Jones was sold for a paltry $100m to a private equity firm called Anchorage Capital Partners. Only eight years earlier the South Africans had fought a somewhat bitter takeover battle to buy David Jones for $2.1bn and were hopeful of creating, together with their existing retail chains, a truly leading southern hemisphere retailer stretching from Cape Town to Melbourne. Sure, in the past few years they sold the David Jones Sydney store in Castlereagh St for $510m and repatriated another $90m in dividends back to South Africa. They have also kept ownership of the David Jones store in Melbourne’s Bourke Street Mall, which could be worth as much as $250m.

‘Sad’ situation

But over eight years of ownership the South Africans looked to have burnt through at least $1.2bn and countless more hundreds of millions spent on refurbishments, IT, failed food ideas and other day-to-day running costs.

At least for the past year, but likely as far back as 2020 when the pandemic shut down its stores, Woolworths Holdings had been guided by investment bankers as they plumped up the old dame for sale, looking for somebody, anybody, to take David Jones off their hands and retrieve some money from their disastrous experiment in Australian department stores.

“I think the current situation is rather sad when you consider the price paid for it, it is a sad end to an era,” former 1980s entrepreneur and one-time David Jones owner John Spalvins said.

Before Spalvins’ sprawling conglomerate Adelaide Steamship collapsed in the wash-up from the 1987 stock market crash, he helped transform David Jones into the glamorous up-market department store of the 1980s as he invested heavily in the store and its expansion. Its famous advertising line of “there’s no other store like David Jones” became synonymous with the retailer under his watch and it underlined the uniqueness and sense of superiority the store both had and had a right to claim.

“The 1980s were the glory days when David Jones would make that sort of figure ($100m) profit in a year. It was a time when retailing went from strength to strength and people like then managing director Brian Walsh had a vision, and the place was expanding, it was optimistic and it was go, go, go,” Spalvins said. “It was the era when people came to have a social outing at David Jones, women came from the country and spent time looking around and browsing around the store.

“And we had a vision. We were expanding, David Jones went on the acquisition trail. David Jones had a vision back then and I think that has been lost. I think the South Africans did not have vision, they were too far removed.”

David Jones did expand under its South African owners, just in all the wrong places and for all the wrong reasons. A store expansion strategy in New Zealand was halted after only a few years of trial, food halls within prime David Jones stores that were to offer the best of local produce were opened with huge fanfare and later shut down after losing $15m a year.

Current David Jones boss Scott Fyfe, who will run the chain for its new private equity owners, agrees about that loss of vision.

“I think you are probably right on that,” he said. “But I think for us it goes a level above vision, to purpose. Why does David Jones exist? So we have very much developed our ‘vision 2025’ strategy and beyond based on a preface that is to inspire like no other because basically department stores need to inspire customers, inspire its people and its partners.

“We should be able to differentiate David Jones on what we offer customers, the experiences we put in place and the curation of world-class brands.”

That’s at least a good place to start for a return to the type of vision Spalvins helped foster, a premium shopping experience when so much about retail these days is formulaic. To make David Jones the drawcard in a shopping centre rather than just a thoroughfare for shoppers to get from the car park to the food court.

What went wrong

Fyfe’s “inspire like no other” line is eerily similar to the “there’s no other store like David Jones” jingle of the ’80s. And if given half a chance by the private equity owners, who have promised to invest in stores and improve the luxury feel around customer experience, it might just work.

But it didn’t have to end like this. Woolworths Holdings had a right to feel confident when it bought David Jones in 2014. A leading retailer in its home country with a history going back to 1931, it had in the late 1990s bought a controlling stake in another much-loved Australian fashion brand, Country Road.

When it later launched its takeover bid for David Jones, led by then CEO Ian Moir, it believed that along with its strong portfolio of brands that could be stretched across geographies, a combination of Woolworths Holdings and David Jones would fashion a southern hemisphere champion that could compete strongly with global apparel retailers such as Zara, H&M and Uniqlo.

But the deal’s ultimate failure began with the takeover. Woolworths Holdings paid way too much for David Jones, and the hole it dug just to buy the department store had it hamstrung from the start. Making matters worse, through a cunning corporate manoeuvre, billionaire retailer Solomon Lew forced Woolworths Holdings to buy him out of his minority stake in Country Road to complete its David Jones deal – Woolworths Holdings handed over another $210m to Lew on top of the $2.1bn for David Jones.

Almost immediately Woolworths Holdings’ new management team were beset with problems. Much-needed investments in stores and IT systems were top of the list but hard to justify given the inflated price it paid for the business. Then there was a revolving door of David Jones CEOs, churning through four bosses between 2014 and 2019 which unsettled staff and its ability to execute its strategy.

But that is not to say Woolworths Holdings let the David Jones stores go unloved. It unveiled a grand $400m renovation and re-imagining of its flagship Elizabeth St store in Sydney, greatly expanding floorspace to entice shoppers with its luxury women’s fashion, shoes and cosmetics floors. This grand renovation was to return David Jones and its Sydney flagship to its rightful place as the nation’s glamour store. Just wait until shoppers saw the grandness, Woolworths Holdings executives told each other, it will match it with the finest stores in London and Paris. It was set to bring David Jones’ unique heritage into a state-of-the-art new era, the retailer promised.

That renovation, which went for years, disrupted trading but was finally completed in 2020 – just in time for Covid-19 and lockdowns. While it could trade online, it was a crowded market with other much bigger players such as Amazon, eBay and rival Myer also spruiking its wares to a nation stuck at home.

“Department stores both in Australia and internationally have been facing unique challenges in the last several years – some of which have perhaps been expedited by Covid-19,” says Dr Eloise Zoppos, from Monash Business School’s Australian Consumer and Retail Studies unit.

“Online shopping, for example, has posed a real challenge to department store retailers.

“The other big question for David Jones and other department store retailers, is how can they differentiate themselves from the brands they sell? How can they create a great, premium experience to bring customers in their doors? This has been difficult over the past three years due to the pandemic.”

The future awaits

To be sure, it’s hard to convey that sense of unique David Jones identity, glitz and glamour, via a laptop screen or mobile phone. Those expensive chandeliers and piano music and $400m in renovations meant nothing to shoppers locked up in their homes.

For Professor Gary Mortimer, a retail expert at Queensland University of Technology, David Jones lost its identity under Woolworths Holdings ownership.

That sense of luxury the brand promoted enticed shoppers to gaze at the opulence on display. But it’s a very different picture in the suburbs where the bulk of its stores are located.

“They (David Jones) understand that a big two or three-level department store in the suburbs no longer works. When you look at a modern-day shopping centre, it has multiple brands all under one roof, which was essential to what big full-line department stores offered in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s,” Prof Mortimer said

Now, as Woolworths Holdings licks its wounds and the new private equity owners prepare to move in, David Jones is gearing up for the Boxing Day sales that could set the trajectory of its fortunes for 2023.

During this crowded hurly-burly of retail frenzy the grand old dame of Australian retail has to rise above the pack; to let the customers know they are somewhere special, and that indeed there is no other store like David Jones.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout