Liddell power station workers on Mike Cannon-Brookes’ plans for AGL transition

From where they sit inside Liddell power station, AGL Energy’s chief operating officer and veteran workers are both exasperated and excited by tech titan Mike Cannon-Brooke’s attention.

In a small portacabin packed with high-vis shirts and hard hats, the shadow of Mike Cannon-Brookes looms large.

The tech titan spent much of the past year waging a series of high-profile battles against AGL Energy, first as a takeover target and then to defeat its plans to split the company through a controversial demerger.

With the aircon rattling behind him at the site of AGL’s Liddell power station, Markus Brokhof lets out a small grimace when I mention the billionaire’s name.

He insists there’s no beef with the climate crusader – and now AGL’s largest shareholder – but says calls for the early closure of the nearby Bayswater coal-fired power plant are unrealistic.

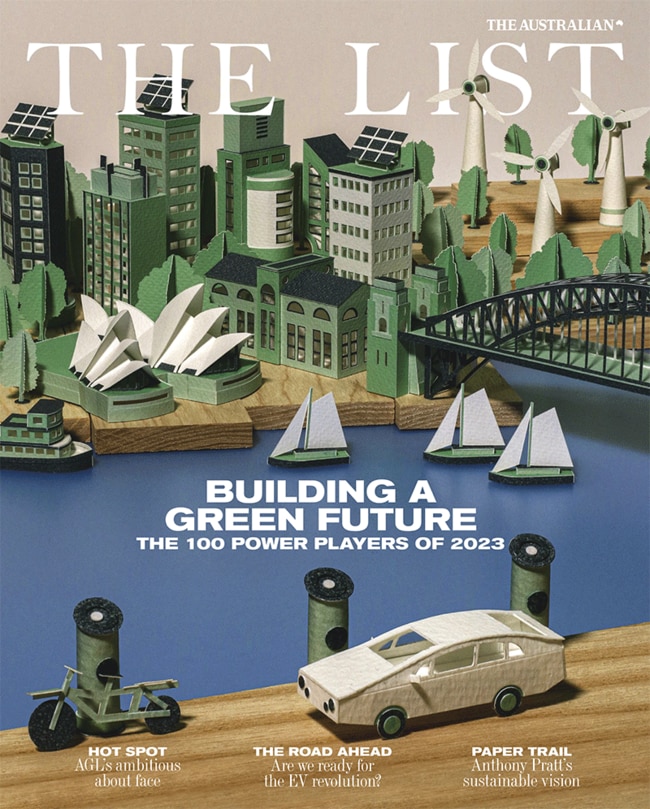

The List: Green Power Players will be published online and in print on Friday, February 24.

“I think you need to find the common target,” says Brokhof, AGL’s chief operating officer. “You can’t just bombard the company with things which are separated from reality.”

The high-profile investor is pushing the 185-year-old utility, Australia’s biggest polluter, to speed up its move to green energy by lining up its business with global warming of 1.5°C. It is considered the world’s most ambitious climate goal.

But on the ground here in New South Wales coal country, the feeling is Cannon-Brookes’s plan is unworkable given the pivotal role the fossil fuel still plays in propping up the electricity industry.

“It’s obvious that AGL as a company cannot fulfil 1.5°C. If we did agree to it, I would have to put a closure notice tomorrow on all three of our coal sites,” Brokhof says, gesturing to the Hunter Valley landscape beyond the window. “So we do it, but then our company will not survive.”

It’s clearly been a draining year for AGL executives who have had to go back to the drawing board and rethink their strategy twice: no straightforward feat for a company facing falling profits, high staff turnover and unpredictable policy from the federal government.

The fight over reinventing AGL also encapsulates the difficulty of making good on a pledge such as net-zero. A pledge that has been overwhelmingly backed by Australia’s top businesses, even if there is little to show so far that ambitious mid-century targets will be met.

Brokhof is clearly exasperated by the idea of transforming the company overnight. But he also wants to make it clear that doesn’t mean AGL is without a plan.

Under newly appointed chief executive Damien Nicks, AGL aims to develop New South Wales’s Bayswater and Victoria’s Loy Yang power plants, and South Australia’s Torrens Island gas site into major energy hubs spanning hydrogen through to batteries.

In the Hunter Valley, several hundred workers are bracing for change. The half-century-old Liddell power station will permanently close its doors in April.

Together with the more modern Bayswater coal-fired power station – just a stone’s throw from Liddell – the two facilities provide up to 30 per cent of New South Wales’s power needs.

No one quite knows what will happen once the Liddell facility is taken out of the equation, but AGL is belatedly rolling out a scheme to replace the lost generation with green megawatts.

Across the 10,000 hectare site, re-named the Hunter Energy Hub, will sit a sprawling array of energy generation developments aimed at tapping into a surging demand for green fuel.

The Liddell Core Precinct, located some 230 kilometres northwest of Sydney and 110km from the Port of Newcastle, will feature hydrogen production, green metals, data centres and battery storage with a mini-hub to the south targeting green cement, glass, advanced manufacturing along with paper and pulp.

The Antiene Precinct to the north will include solar but also plans to tap into agriculture, while the nearby planned Muswellbrook pumped hydro facility and Bowmans Creek wind farm would collectively supply nearly half of the lost capacity of the Liddell power station.

A big part of the plan is getting the site’s diverse team of engineers, technicians, maintenance and outage staff signed on to the new vision. About half Liddell’s 200 staff have agreed to make the short trek to Bayswater, which won’t close until 2035 under current plans.

One worker, Jimmy Ward, was an apprentice when Liddell first cranked into action in 1973. Fifty years on – and still an AGL employee on site – he was given the role of switching off the first of the plant’s four coal-fired steam turbines last year.

But before AGL can push into the future and industries such as green hydrogen, it also has to weigh up how it can bring along an ageing workforce and attract younger talent to the business, lured by working on a new type of industry for the region.

Len McLachlan, in charge of Liddell and Bayswater operations for AGL, concedes not everyone is quick to jump on board with the shift.

“It is a bit disconcerting because I went around to every crew and every team and said to them, ‘How are you feeling about the fact you joined the power station and had a whole career ahead of you?’,” McLachlan says while grabbing lunch in the mess room.

“And now you’re looking at it going, ‘Oh actually, I’m gonna have to find another job in 10 years, or 12 years’. And so that’s definitely what people have been facing.”

Still, as the energy hub has moved from a concept into concrete projects, some workers’ ambivalence is starting to change.

“What I’ve noticed is as we’ve started to articulate the vision around the energy hubs, the employee interest in what that means and the opportunities is growing. I hope we are really now painting a bit of a better picture. We’re not just about closing power stations, we’re actually about replacing the business.”

Now the challenge is to keep the Bayswater plant pumping coal-supplied power into the grid while rebuilding new energy projects on site to take advantage of its access to rail lines, water and existing electricity infrastructure that sends supplies direct to the main demand centre of Sydney.

“With Liddell, we had to make sure that we maintained and kept our critical people to run the plant. Because there were a whole bunch of operators that could retire at any point. And we actually had to say, ‘Look, we need you to actually stay and help us run the plant safely till we close the plant’,” McLachlan says.

“And so we did a retention plan. And the same thing will happen with Bayswater. It’s still 11 years away. But time goes on. And I think, as we build out, the next five years will really start to tell because we start to see the fruition of some of these new projects coming online, and even new partnerships with different types of businesses.”

AGL recognises it cannot pull off an expansion like this alone. It teamed up most notably with Andrew Forrest’s Fortescue Future Industries for the construction of a hydrogen plant that would produce 30,000 tonnes of the fuel each year.

The pair is studying an ambitious plan to produce green hydrogen – using water from Lake Liddell and power from AGL’s planned renewable energy hub – for export or for use in the New South Wales power grid.

For its part Fortescue says the initial feasibility study would give an indication of whether production could be scaled further at Liddell, potentially giving the Hunter coal region a new export industry as thermal coal-fired generators are phased out across the globe.

Travis Hughes pops his head in the room to check on a meeting with Brokhof. As the AGL executive responsible for its energy hubs, Hughes has a unique perspective on whether the company is ready to re-think its core role as a coal supplier.

He points out the company has already reinvented itself several times over from a gas producer and pipeline operator through to electricity retailing and then coal-fired generation just on a decade ago.

“I think it’s interesting to think about the role AGL is trying to play now, in what is probably the biggest shift in the industry,” Hughes says.

“We are sitting here today thinking about whether hydrogen retailing might be an industry in the future. Whereas the person in my chair in 10 years’ time will be like ‘Yes, of course it was’. And they’ll be talking about what the next technology is to jump into.”

The NSW government has thrown its support behind AGL’s closure plans, as part of its target to halve carbon emissions in the state by 2030 and to phase out the contribution of coal-fired power plants by 2040. Premier Dominic Perrottet unveiled a plan to establish the state as a major hydrogen exporter, with up to $3 billion in incentives on offer as part of the package, including tax breaks for hydrogen producers.

NSW Energy Minister Matt Kean says the strategy is aimed at attracting more than $80bn in new private investment into hydrogen projects, with the industry tipped to eventually support 10,000 jobs.

For AGL managers such as McLachlan, separating the hype of the energy transition from reality is also another big talking point within the industry.

Origin Energy has pointed out, for instance, that while the national electricity market currently has three gigawatts of renewable capacity scheduled to come online, it needs an estimated 28 gigawatts by 2030 as coal-fired power stations wind down.

“From my own personal view I’m looking at other countries and saying, ‘Who has pulled it off successfully yet?’.

That transition is still occurring, so you still need gas and you can’t get away from one or the other because some of the technology we’re going to need to actually pull it off effectively still needs to be invented,” McLachlan says. “When we first announced Liddell was closing, people couldn’t picture what could replace it. But that’s starting to change. So you can see that growth in thinking. So when it comes to anti-coal, our employees are actually more than willing to see a transition occur. They want to be a part of it.”

Certainly, the sums involved to pull off this green vision are eye-watering.

AGL thinks it would need to find up to $20bn to accelerate its exit from coal-generated power. That sum comes on top of Anthony Albanese’s $20bn election commitment to upgrade transmission infrastructure, a $62bn clean energy plan outlined by the Queensland government, the $32bn Energy Infrastructure Roadmap in New South Wales, and $20bn in spending in Victoria.

AGL hopes to realise its decarbonisation plans in the next 12 years, as the company looks to supply a total 12 gigawatts of renewable energy assets by the time it exits coal in 2035. The clean energy plants would include 6.5 gigawatts of primary generation, such as wind and solar farms, plus 5.5 gigawatts of firming capacity, including batteries and pumped hydro.

To achieve that target AGL says it would need to build 12 new wind farms the size of its 453-megawatt Coopers Gap operation in Queensland, and another eight new solar plants the size of its 102-megawatt Nyngan solar farm in far-west New South Wales. It would also need 14 new 250-megawatt grid-scale battery stations, supported by at least eight other long-duration energy storage plants, such as pumped hydro operations, hydrogen or bio-fuelled backup energy projects.

For now, AGL has 3.2 gigawatts of firming capacity in its development pipeline, including a 250-megawatt battery at Torrens Island in South Australia, slated for completion in mid-2023. It has planned a 50-megawatt battery in Broken Hill, the 500-megawatt Liddell battery, the 200-megawatt Loy Yang battery and the 250-megawatt Muswellbrook pumped hydro project in partnership with Idemitsu Australia.

Brokhof is fond of pointing to his own experience growing up in Germany’s Ruhr Valley, where billions of tonnes of coal was dug up over several centuries across an industrial landscape. Since the final mine closed in 2018, the region has now been transformed into a service-led economy, proving for Brokhof at least there is life after fossil fuel.

“An energy hub is not just generating power, it is also about creating a vision of a circular economy,” he says. “When you look at all the supply chain problems and look at all the ambition now to transition into a renewable future, we will not have sufficient suppliers around Australia which will deliver all the kits and all the devices which we need here. We need to start thinking about how we develop this here and we think we can be a part of that.”

Cannon-Brookes will of course be watching on and pushing the company to do even more. Despite the upheaval, Brokhof insists AGL is better off with the Atlassian co-founder on its side.

“We have this narrative about a traditional company with 185 years of history and then the new tech player, which has been a bit sensationalised. But look, it is good that he has an interest in the company,” says Brokhof. “And all we say is, ‘Come and talk to us and we’ll do the same. And let’s go together on this journey’.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout