BHP sees limited ‘champagne’ role for hydrogen in energy mix

Hydrogen will fill a niche role in the global energy mix rather than be a staple fuel as it struggles to compete against other sources of renewable generation, a BHP executive has forecast.

Hydrogen will fill a niche role in the global energy mix rather than become a staple fuel, a BHP energy executive has forecast, as the energy source struggles to compete with the rise of other sources of renewable generation.

Lee Levkowitz, head of BHP’s energy, carbon and technology research, said there were two distinct visions for hydrogen, but the world’s biggest mining company presently sees it playing a small but lucrative role in the global economy.

“It could be champagne or it could be tap water,” Ms Levkowitz told The Australian. “There are certainly opportunities in the global energy transition where it will be needed, but there are a variety of decarbonisation technologies where it is not necessarily the foremost technology.”

To reach its goal of being a major global hydrogen exporter, Australia will need to spend $592bn by 2050, with about $369bn or 62 per cent flowing into new wind capacity and the remaining going to solar, according to green energy researchers at BloombergNEF.

Some 812 gigawatts of wind and solar power will be needed in less than three decades, more than 10 times the current capacity of the national electricity market, driven by greater demand from electrolysers. “Australia has big hydrogen dreams, but has its work cut out to turn them into reality,” BloombergNEF says in a report on Australia’s path to a net zero economy.

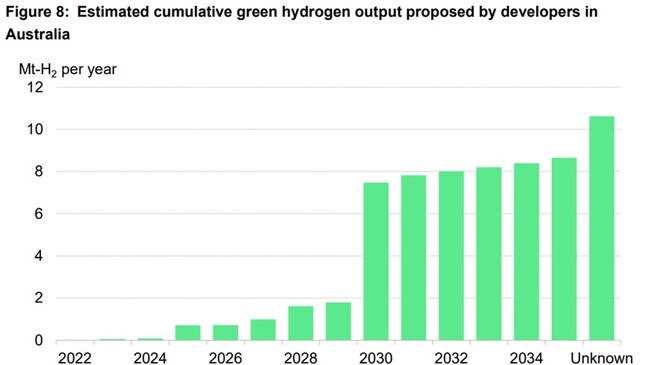

“Australia also already boasts a pipeline of green hydrogen projects representing up to 10.6 million tonnes of annual production. However, a lack of specific government targets, few concrete offtake agreements, stiff competition from other potential export markets, and massive infrastructure challenges mean Australia’s ambitions are not guaranteed.”

The federal government in its May budget promised $2bn to drive down the cost of producing green hydrogen, its first response the US Inflation Reduction Act which offers billions of dollars to boost clean energy production.

The policy has drawn a wave of investment into the US and Australian renewable energy advocates have warned Canberra risks missing out.

“The International Energy Agency says the world needs roughly $US4 trillion ($6 trillion) in clean energy investment by 2030 … The US is very much taking a carrots approach to that, rather than a stick analogy,” said Ms Levkowitz.

“It is a pretty big carrot.”

The policy contrasts with Labor’s “safeguard mechanism”, which will require Australia’s 215 largest emitters to reduce emissions every year, a move Ms Levkowitz said was more a “stick” approach.

Ms Levkowitz said Australia should focus on its strategic advantage in boosting the supply of critical minerals which will be needed in vast quantities to build new renewable energy technologies.

“The world needs an incredible amount of those future-facing commodities to the transition. From a carrot approach, it makes sense to put efforts into incentivising the enhanced production of upstream resources,” Ms Levkowitz said. The role of hydrogen in the world’s energy transition is contentious. While some proponents such as Andrew Forrest believe it will emerge as a substitute to LNG, others insist it will be too expensive and difficult to transport to replace other renewable energy sources.

Asia, most notably Japan, has put hydrogen at the heart of its energy transition plans. In April, Japan set a new ambitious target of boosting supplies of hydrogen to 12 million tonnes by 2040, replacing its previous goal of 2 million tonnes by 2030.

The biggest impediments to so-called green hydrogen – where renewable energy is used to split water into its core elements – are costs and scale.

Australia lacks sufficient renewable energy generation assets to power the electrolysis process, and creating a hydrogen industry would require a vast expansion in zero-emission sources. If Australia is to achieve that then Canberra would simply embrace electrification, critics of hydrogen say.

“Over 500 petajoules of electricity generated by solar and wind will be required to power electrolysers in Australia in 2050,” BloombergNEF says in its study. “This represents over 97 per cent of all electricity generated to produce hydrogen in Australia in 2050. Around 2.5 per cent of the electricity generated to produce hydrogen will come from coal and gas paired with carbon capture and storage.”

Moving steelmaking away from coking coal and natural gas to smelting using electricity and hydrogen has been touted as a breakthrough for the steelmaking industry. However, BHP has said electric arc furnaces, which are seen as one potential solution, are best suited to processing scrap steel and high-grade direct reduced iron.

Hydrogen will help decarbonise shipping, steel, and refining, but remains niche elsewhere, according to BloombergNEF.

“Hydrogen is less competitive where alternatives already exist or are emerging. This includes the power sector, buildings and industrial sectors outside of steel, such as petrochemicals (excluding use as feedstock) and cement. Hydrogen plays a limited role in heavy road transport,” the report states.

Green hydrogen can be transported as ammonia and is favoured by big buyers in both South Korea and Japan.

Australia had the potential to replicate its giant coal and LNG export industries with hydrogen given its vast resources of low-cost renewables and close trading links with Japan and South Korea, Goldman Sachs said in 2022.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout