What opening up after the Covid pandemic may look like down the road

After an initial burst of activity, the return to normal won’t necessarily mean a return to the way of doing things before the pandemic.

New figures released by the Australian Bureau of Statistics last month reveal the impact of the coronavirus on the workforce. Not so much in terms of job losses – although that is part of the story – but in the way the job market is being contorted with falling demand for low-skilled jobs and rising demand for high-skilled jobs.

Impact on housing

Indeed the demography of work combined with changes in consumer behaviour are affecting the outlook for the property industry. On the one hand the shutdown in immigration could have been expected to reduce demand for housing.

However, this has been offset in the short term at least by a greater appetite for home ownership, perhaps among millennials who have been frustrated by the cost of housing.

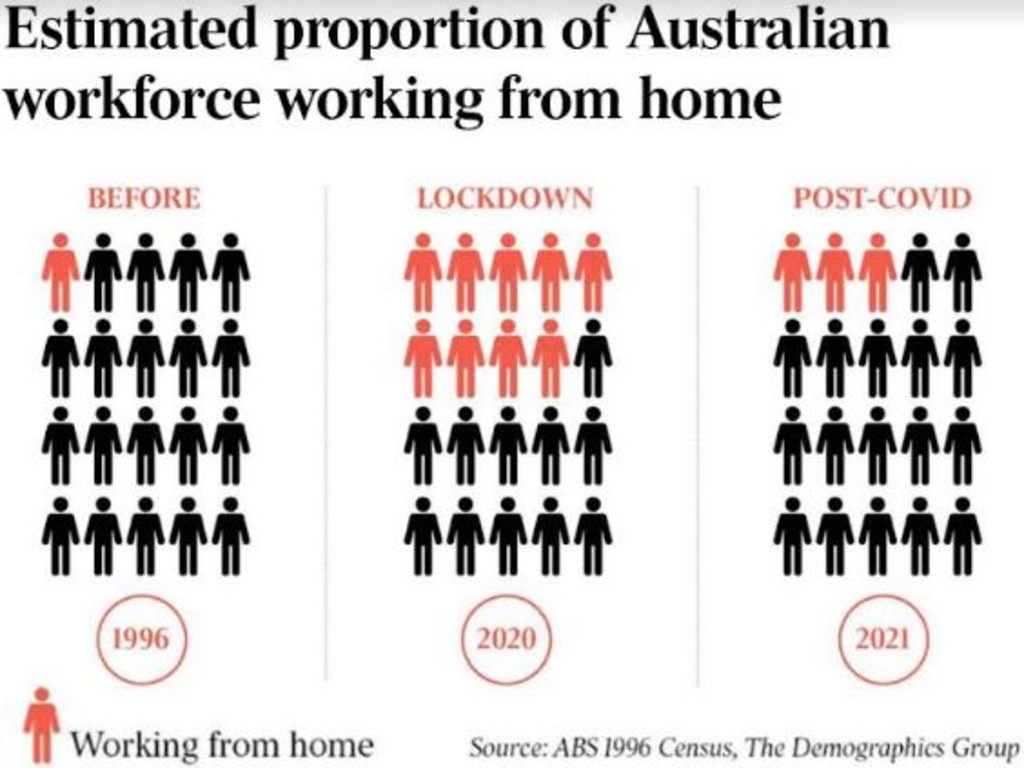

But with falling interest rates plus the pragmatic need for a house with a garden in the late-30s stage of the life cycle (when family needs trump preference to be close to the city centre) there’s a rejigging of priorities. And especially in a world in which working from home suddenly becomes an option.

This recent trend towards greater levels of home ownership is driving demand for three and four-bedroom houses (including a Zoom room) in middle and outer suburbia, and in lifestyle towns within striking distance of the city centre.

Impact on jobs

But the demographic effects of the coronavirus don’t stop with the housing market. The job market is being reshaped by the pandemic.

The ABS classifies the workforce into 427 occupational categories for which job numbers are published every three months. Figures for the three months to August were released last month.

These occupations are slotted into one of five skill level categories. Generally Skill Level 1 jobs require a university degree or high levels of technical proficiency.

This category includes, for example, general practitioners, accountants and registered nurses. Skill Level 5 jobs require only on-the-job training and include, for example, shelf fillers, kitchen hands and sales assistant.

Across the year before the arrival of the coronavirus (February 2019 to February last year) the number of Skill Level 1 jobs increased by 4 per cent to 4.547 million.

There also was growth in Skill Levels 2, 4 and 5 across this year, ranging from 1 per cent to 3 per cent.

Only Skill Level 3 jobs contracted (by 3 per cent) across this year.

Bunching, not hollowing

A fair pre-Covid overview is that the job market was “hollowing out”, with job growth at the top and at the bottom of the skills spectrum and job loss in the middle.

However, the coming of the coronavirus changed this narrative.

Across 19 (Covid-affected) months between February last year and August this year, the number of workers employed in Skill Level 1 jobs increased by 6 per cent.

But there has been a progressively reducing demand for less skilled jobs. Indeed, net change in the workforce during this period has resulted in fewer jobs across Skill Levels 2-5 inclusive.

In fact the pattern of job loss is instructive: a loss of 1 per cent for Skill Level 2 followed by losses of 2 per cent for Skill Level 3, 4 per cent for Skill Level 4 and 9 per cent for Skill Level 5.

Covid is reprioritising the workforce based on skills.

So, in the pre-pandemic world the workforce was hollowing out by diminishing work opportunities for middle Australia.

But in the post Covid-19 world, or at least for the past 19 months or so, the job market has “bunched up”, preferencing the highly skilled over the non-skilled.

The importance of skills

The impact of this bunching effect is evident in another dataset called Small Area Labour Market estimates produced by the National Skills Commission under the auspices of the Department of Education, Skills and Employment. Modelled from the ABS’s quarterly labour force surveys, this dataset estimates labour force (employed plus unemployed) by suburb (or SA2).

When labour-force skills between March last year and June this year are mapped across Melbourne suburbs, it is evident the coronavirus has diminished job opportunity across middle Australia and increased job opportunity in the central and inner eastern suburbs. This map effectively shows the ratio of Skill Level 1 workers (by residence) relative to all other skill levels.

Clearly the best thing you can do for your kids, based on this evidence, is ensure that they enter the workforce (in the 2020s) with some level of technical or university training. Skills deliver options and work opportunity across a lifetime including through a pandemic.

Impact of opening up

The question for business and government is whether this revaluing of demand for workforce skills will be carried forward into the post-Covid era and, if so, what are the property implications. Many low-skilled jobs involve interacting with customers and/or co-workers in shops, cafes and factories. Lockdowns and no doubt some business closures caused by the pandemic affect this segment because they cannot carry on working from home.

However, as workplaces reopen there is every reason to expect that many of these lost jobs will be reinstated. The question is, of course, what proportion of diminished jobs will be reinstated (or, indeed, how easy is it for displaced workers to find other jobs).

There is the distinct possibility that consumer behaviour has been changed by the pandemic: more online shopping, more automation and mechanisation in factories, and perhaps lingering reticence among some with regard to mixing and mingling in crowded cafes and restaurants.

I’m not entirely convinced of this reticence argument; in the post-war 1920s Australians wanted to celebrate life.

Indeed, it could be argued that from next year onwards the national mood will be lifted by the prospect (and the reality) of recovered freedoms, in which case there would be heightened demand for events and arts and cultural activities, for opportunities to do what we have been prevented from doing for two years.

And in which case workforce growth might return to the pre-Covid model of strong job growth at the upper and lower ends of the skills spectrum.

This so-called return to normal would drive social activity around the central business district and the inner city as well as in suburban hubs and lifestyle precincts.

Initial burst of activity

The immediate effect of opening up will enliven precincts and places driving business and job growth. There will be a surge in demand for interstate and international travel as long-promised catch-ups are realised. There surely will be a surge in skilled migration as businesses target specific skills that simply aren’t accessible in sufficiently deep labour pools within Australia.

There must be a surge in demand for international students and maybe also incoming seasonal workers, depending on the season in which the borders are opened.

I am not convinced there will be an outflow of Australians looking to resume their expat lifestyle: Australia still represents a relatively safe haven in a still Covid-affected world.

In other words the process of opening up the economy, when viewed from the perspective of the job market in August this year, suggests that it is the least skilled workers (including the young, the immigrant) who have most to gain.

And that’s because it is the least skilled workers who bore the brunt of the lockdowns and diminished work opportunity.

Long-term opportunities

I suspect that the long-term effects of the pandemic on the Australian way of life won’t be evident next year but will be revealed progressively from 2023 onwards after the initial excitement of opening up subsides. And in this world I think we will see:

● Stronger demand for suburban hubs including commercial office buildings.

● More demand for warehousing and logistics centres and especially in middle suburbia (near motorway access).

● Tightened and maybe even heightened demand for ultra-premium office space in the CBD (for ASX 200 business administration).

● Niche opportunities for retail and commercial space in regional cities and selected lifestyle towns.

The post-Covid world will carry forth a great legacy of demand for deeper local pools of skills and training and for a range of lifestyle and commuting options.

The car will still be important, but the next generation of office workers will be more agile in their pursuit of mobility. This could include, for example, the regular use of car, bike, scooter, walking, rideshare apps and work from home.

The bottom line for property businesses in particular is that opening up doesn’t mean returning to the pre-Covid way of doing things.

If anything, opening up means an opportunity to think more boldly, more creatively about the property requirements that will help Australians live the lifestyle they want to live in the 2020s and beyond.

Bernard Salt is executive director of The Demographics Group. Research by data scientist Hari Hara Priya Kannan.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout