Secret house business

The tightly held mansions of Australia’s wealthiest families rarely come to market.

Far grander now than it was even after its 1884 boom-time completion, the heritage Italianate mansion Raheen in Kew ranks as Melbourne’s best-known privately owned trophy home. While its philanthropic chatelaine Jeanne Pratt, widow of billionaire packaging businessman Richard Pratt, welcomes appreciative guests into its grounds, the red brick Raheen is one of the city’s most tightly held homes.

MORE: The List: Australia’s Top 50 Mansions

It last sold 38 years ago for $2.567 million. The Pratts bought it in 1981 from the Catholic Church, which had owned it for 64 years. It has only had four owners.

Raheen sits among the select few admired homes that are seemingly off limits to buyers in the capital cities around Australia. These are family homes, occasionally intentionally hidden from the public by hedges, that are very much family heirlooms. Their alluringly exclusive status enhances their eventual selling price, should another family ever get the opportunity to purchase.

Swifts, in Sydney’s Darling Point, was keenly desired when its two-decade ownership by the Catholic Church ended in the mid-1980s. But horse trainer Carl Spies had an in with the church and nabbed it for $9 million, then a national non-waterfront record.

Swifts had been one of Sydney’s most admired trophy homes since it was built in the 1880s for the Tooth brewery family, with its soirees regularly gracing the newspapers’ social pages. The Gothic Revival home was the talk of the town when the Tooths sold it to their brewery rivals the Resch family in 1900, when Robert Lucas-Tooth went to the UK to sit in the House of Lords.

The Moran healthcare family have seen themselves as Swifts’ “custodians” since 1997 when they paid $12 million to the mortgagee after Spies had become overextended. The mansion had fallen into disrepair. “Two days after we exchanged contracts the ceiling collapsed,” Shane Moran recalls. The property is expected to remain in family ownership for a very long time to come, he says, noting there is still work in progress. “It is all good fun, but you have to be a little mad .... my wife calls it a big black hole,” he says.

The Moran parents, the late Doug and his widow Greta, spent $14 million over the first two years restoring the home, which has a ballroom purposely built bigger than the ballroom in the NSW Governor’s residence. A rare Fincham & Hobday has been installed in the ballroom’s organ loft.

Christie’s International agent Ken Jacobs, who last sold the home, says Swifts would rank as a special property anywhere in the world. “A sandstone castellated gothic revival mansion on more than three acres of level land within 4km of an international CBD is rare by world standards,” he says. “The fact that it has survived and been revived, and has an ownership history ranging from beer barons to the Catholic Church, introduces another interesting dimension.”

Carved into the façade is the Tooth family motto Perseverantia Palmam Obtinebit – “Perseverance gains the prize”.

Just down the Darling Point pensinsula, the Bushells Tea family has owned Carthona since paying £10,500 in 1941, and the third generation of the family is in residence. The 1840s home was built by the NSW surveyor general, Sir Thomas Mitchell.

Nerida Conisbee, chief economist with realestate.com.au, says owning an old, stately home is a symbol of wealth and status. “Those who are wealthy enough to afford them in the first place usually don’t have any financial imperatives to sell them, instead passing them on through generations to other family members who appreciate the sentimental value,” she says.

“The number of luxury homes in Australia is limited, especially those in amazing, sought-after locations, so it’s appealing to be able to hold onto them to showcase your wealth. Housing in most parts of Australia gains value over time, so purchasing expensive luxury homes is a way to park money with good investment incentives.”

No amount of money can wrest the most prized homes from their fortunate owners.

Nearing a century of ownership is Cranlana in Melbourne’s Toorak. Formerly known as Fyans Lodge, the home of Charles Mills from the Uardry pastoral run, it was bought by department store founder Sir Sidney Myer and his wife Dame Merlyn (nee Baillieu) in 1920. The Clendon Road home was remodelled, providing much needed work during the 1930s Depression.

Cranlana’s ballroom wasn’t exclusively used for entertaining Melbourne’s elite either. Son Kenneth Myer’s wedding to Prudence Marjorie, née Boyd, saw 800 Myer emporium staff attend a party in 1947. Dame Merlyn resided at Cranlana until her death in 1982, some five decades after Sir Sidney’s death and it is still owned by the Myer family and used with philanthropic intent.

Atlassian billionaire Mike Cannon-Brookes continued a charitable tradition when Double Bay’s Fairwater last month hosted the Australian Ireland Fund garden party overlooking Seven Shillings Beach. The tech startup billionaire, a co-founder of the software giant, bought the harbourfront home, settling the record-setting $100 million acquisition without any initial mortgage. It was the home of the late media family matriarch, Lady Mary Fairfax, and last traded in 1901 for £5,350.

The neighbouring Elaine had been sold by the family in 2017, also signalling a baton change. That was bought by Atlassian’s co-founder Scott Farquhar for a then record $71 million.

The previous Australian record had been set at Vaucluse, where Chinese wealth secured the newly built hillside home of James and Erica Packer. The Chinese born buyer, Dr Chau Chak Wing, the chairman of the Guangzhou-based property development company Kingold Group, had long held Australian residency.

Contemporary homes have particular appeal for Chinese buyers. Mortgage broker John Symond had two leading agents head off to China in 2016 to seek buyers for his Point Piper home Wingadal, built in 2007 after the earlier demolition of the Guilford Bell-designed Hordern family home. It didn’t sell, notwithstanding a $100 million-plus offer.

Billionaire trucking magnate Lindsay Fox owns two of the best homes, in Sydney and in Melbourne, plus a clifftop weekender at Portsea on the Mornington Peninsula.

On Sydney Harbour, the Fox family has Boomerang, the Elizabeth Bay waterfront bought for $20 million from cleaning entrepreneur John Schaeffer in 2005. It was three years earlier when the home broke through the $20 million barrier. When the Fox family moved to enclose the exquisite wrought iron front gates, Sydney City Council sought occasional public access.

Boomerang, now in 4200sq m of Myles Baldwin gardens, dates from the 1920s, when the wealthy music book publisher Frank Albert paid $25,000 for land within the Elizabeth Bay House subdivision. Albert commissioned architect Neville Hampson to design the home in the popular Hollywood architectural style, Spanish Mission, at a cost of £60,000.

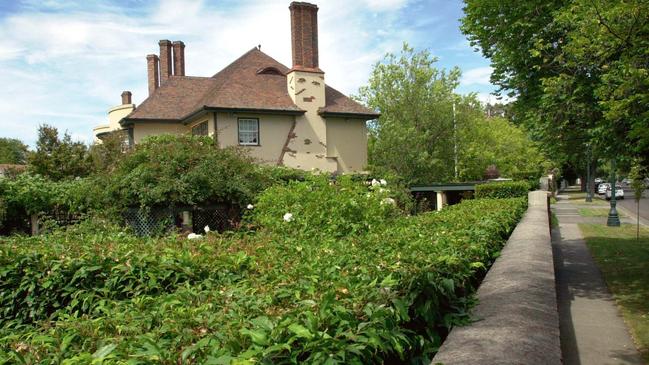

Lindsay and Paula Fox retain Eulinya, a heritage-protected arts and crafts home in Toorak they bought in 1978 for $570,000 from the lady mayoress, Lady Lilian Coles, wife of Sir Arthur Coles of the supermarket family. The home had been designed by English architect Walter Butler in the 1920s for Sir William McBeath, chairman of the State Savings Bank. A 1927 edition of Australian Home Beautiful described the 22-room mansion as “a 20th century interpretation of old English architecture”.

Most of the grander houses of Melbourne aimed to emulate the greater houses of Britain, although many were also influenced by trends in NSW, Tasmania and even India, the architecture professor Miles Lewis has noted. There were some 1200 houses with 20 or more rooms across Australia, most in Melbourne, at the end of the 19th century. Lewis has followed the decline of the boom-time Victorian mansion, noting it began in the 1893 financial crash. “Not only did mansion building largely stop, but demolition and con-version began,” he wrote, calculating the decline to 515 grand homes by the 1930s. “Some had been demolished to free up their sites for subdivision, but it was more common to subdivide around them.”

The demolition peak occurred around 1955. “It was in the following year that the National Trust acquired Como, and so, tentatively, the tide began to turn. Today most of the true mansions that survive are in some sort of public or institutional ownership.

“Only odd examples like Raheen, Coonac and Sebrof are privately occupied. And most have lost their grounds,” he noted of the remaining 19th century homes in his essay “Housing and Status in Victoria Victoria”.

There are a number of reasons these trophy homes do finally trade, and occasionally it is because there’s no choice. The last time The Hermitage at Vaucluse sold was in 1975 when the Hemmes family paid $500,000. It was a credit squeeze fire sale by Dick Baker and his wife, a former Miss California, following the 1974 collapse of his property development company Mainline. Pub baron Justin Hemmes has recently renovated the heritage-listed Gothic residence with the aid of architect Brian Hess of Hess Hoen and landscapers Michael Bates and Daniel Baffsky.

Toorak’s Coonac has twice been sold under bank instructions, first in 1893, when owner John Robb saw the Federal Bank foreclose after his rural losses. Then, after the early ’90s recession, property developer Livio Cellante and his wife Josie lost the home.

One of Toorak’s largest landholdings, Coonac last sold in 2002, to the transport and logistics magnate Paul Little and his wife Jane Hansen. Its $14.5 million sale made it Melbourne’s then most expensive home.

Sebrof, on Orrong Road, Armadale, was in the hands of the Education Department for decades, between 1959 and 1986. It was built for the Forbes family (Sebrof backwards) to a design by Dalton & Gibbons in 1886. The family had sold by 1892.

The home last sold in 2008 through Kay & Burton agent Ross Savas, who says Melbourne has long had a “mentality of keeping and handing it down – far more so than Sydney.

“We have also seen the influx of the overseas buyer coming and buying their initial home, then not selling, but often buying another. These combined factors are creating a bottleneck.”

The acquisitions can also create a compound, not that it is a new pursuit. In Sydney’s Bellevue Hill it was Sir Frank Packer who set about amalgamating his fiefdom. He bought Cairnton for £7500 in 1935, spending a further £28,000 on five separate purchases to expand the holding in the 1960s. Sir Frank’s son Kerry expanded it further in the late 1980s and 1990s by buying four more houses at a cost of more than $8.4 million. Historians point to the compounds in medieval Venice, which offered a sense of family solidarity, defensive in intent against personal vendettas.

The Pratts spent $3.5 million to buy an adjoining 4700sq m in 2006 as they went about sympathetically updating and extending the estate, bringing it into the 21st century.

There are now three buildings on the 1.6ha estate, with Raheen 2 built in 1993 to a design by Glenn Murcutt. Australia’s richest man, Richard Pratt’s son Anthony, who now runs the family empire Visy, founded in 1948, undertook a $9.5 million renovation and Bates Smart extension in 2015, creating Raheen 3.

The original mansion dates from the 1870s, when the Carlton Brewery founder Edward Latham built what was then known as Knowsley. Barrister and politician Sir Henry Wrixon and his wife Lady Charlotte, daughter of financier Henry “Money” Miller, completed the home that became known as Raheen, meaning “little fort” in Gaelic. The Wrixons opened the home to raise funds for the Victorian Ladies’ Work Association, which assisted women in distressed circumstances. It stayed with the Wrixons until 1917 before it was bought by the Catholic Church to accommodate Melbournes most notable archbishops, including Daniel Mannix. There was a 1960s subdivision

After the Pratts purchased it, Jeanne Pratt embarked on her vision to transform it into “a cultural, business and social hub”.

For the homes of mums and dads, who mostly move to accommodate more children, recent resale data from CoreLogic shows that houses sold for a profit have been typically held for a decade or longer. Those that sold for a loss had been typically held for less than six years.

The most common reason for listing a trophy home is the death of the family patriarch or matriarch. The prized homes that last sold in pounds almost always carry a wow factor, attracting headlines when they are listed.

Held for nearly six decades, Armadale trophy home Moorak has been listed by the Salter family matriarch, now in her nineties, for November 29 private auction. It traded for £20,000 in 1961. The home was built in 1888 for warehouseman William Walker.

“The house represents the affluent and turbulent settlement of these boom-era estates,” the Victorian Heritage Register reads.

“Every city has them – those handful of homes in those handful of streets that evoke a sense of yearning from just about everyone who passes by,” Abercrombie agent Jock Langley says. “Moorak oozes heritage, provenance, nostalgia, and an understanding they simply don’t, and can’t, make them like this anymore.

“This is the choicest of locations, where every square metre is prized real estate ... a 2000-plus square metre private escape with a magnificent 1880s Italianate homestead, soaring trees, flower and fruit gardens, a gorgeous old glasshouse, a lovely shady pool, and a coachhouse at the bottom of the garden.

“For the past 59 years, Moorak has been one family’s treasured home. Spend a little time here and it’s easy to see why.”