Navigating the 2020s: From the baby bust to the skills drought

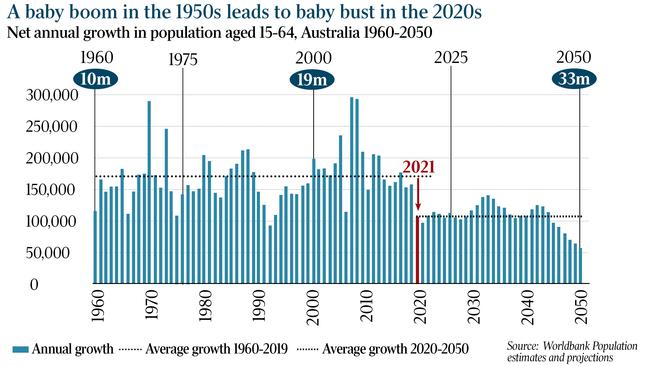

If there was a baby boom in the 1950s then there must be a baby bust in the 2020s as Boomers exit the workforce.

If there was a baby boom in the 1950s then there must be a baby bust in the 2020s as Boomers exit the workforce.

And that was the outlook before the pandemic and our recent troubles with China.

Underlying baby bust

It’s not so much that Baby Boomers (born 1946-1964) are expected to die in droves in the coming decade it’s more that they’re right now exiting the workforce at a faster rate than Millennials (born 1982-2000), and their successors, are entering the workforce. The net effect of different-sized cohorts entering and exiting the workforce is a shallower pool of available labour leading to a skills drought.

Indeed over the 60 years to 2020 the number of Australians added to the 15-64 cohort averaged 175,000 per year helped along by high levels of immigration.

However over the 30 years to 2050 net growth for the age group from which the workforce is drawn (15-64) is projected to drop to 110,000 per year. This assessment is based on ABS projections published November 2018 and so predate the pandemic from March 2020.

So, toss in a few years of diminished immigration because of Covid-19 and average annual growth in the ‘working’ 15-64 cohort (over the projection period) could slump to, say, 90,000. That’s a 49 per cent drop from pre-Covid growth rates for this cohort.

All this very much matters because 15-64-year-olds form households, reproduce, take out loans, buy consumer goods, raise families… and they pay tax. A lot of tax.

However from 2020 onwards this ‘demographic piston’ driving the Australian economy begins to slow down.

Along comes Covid

And so in addition to managing the baby bust during the 2020s the Australian economy must also contend with closed borders that limit access to foreign workers.

Australia’s long-term annual net gain of 250,000 immigrants (includes students, backpackers and seasonal workers) suddenly swings into reverse.

Indeed data from the federal budget papers show that in FY2021 there was a net outflow of 93,000 residents from the Australian continent, the first such loss since 1946 when American troops went home.

We have been operating in unfamiliar net-migration territory for 12 months.

It is possible, I suppose, to ‘make do’ with access to the existing labour pool, to soak up labour displaced by the pandemic, for a year or so. But it’s not what business (and government) is accustomed to.

Rightly or wrongly we have been cherrypicking overseas labour with precisely the required skills for years if not for decades.

However more than a year into the pandemic and with an unemployment rate back to pre-Covid levels we’re stumped as to where additional skilled labour might be accessed.

The second year of closed-borders crystalises a skills drought (which hopefully might lead to wage rises) and must lead to innovative ways of securing labour, including enticing workers from one industry to another.

Over FY2022 some older workers might be encouraged to postpone retirement. Some younger workers might be enticed out of family leave back into the workforce, to work part-time, to work from home – anything – to get the right talent back into the labour pool.

The Australian Bureaus of Statistics provides quarterly estimates of the number of workers employed in 430 occupations comprising the Australian economy.

Just prior to the pandemic in February 2020, the ABS estimated the number of chefs in the Australian workforce at 107,000.

However by May 2021 the chef workforce had recovered to 92,000 which is still 15,000 fewer than had been employed prior to the pandemic.

This means over 15 months some 15,000 chefs have either left Australia because they were a seasonal, backpacker or some other kind of non-permanent-resident worker, or they left the labour force altogether, or they found work in another industry.

The number of cooks has jumped from 41,000 in February 2020 to 44,000 in May 2021 so maybe some of the displaced chefs have found work as cooks.

The same goes for waiters. This workforce comprised 147,000 workers in February last year which compares with 136,000 by May this year. This means that 11,000 waiters employed in February 2020 are now either unemployed, back in Germany, France or Ireland, have left the workforce altogether or have found work in another industry.

The job of ‘office manager’ was down 40,000 positions on pre-pandemic levels while the number of workers working in the job of ‘general clerk’ is down 21,000 over the same time frame.

Maybe there’s less requirement for general office jobs in a post-Covid world because of the greater acceptance of automation (less need for clerks) and because there are fewer workers actually working in an office (that need managing).

On the other hand, in a direct comparison between February 2020 and May 2021, there has been a net increase in the number of electricians (up 13,000), carpenters & joiners (up 12,000) and plumbers (up 4,000).

All those newfangled work-from-home arrangements seem to have created quite an appetite for home improvement. Indeed the family home is a bit like an airport terminal: the greater the dwell time the more money is spent within and on the building.

Outlook for property

And so while the pandemic did indeed cause job losses on a large scale, over time it has also created job growth and some business opportunity.

Not all the expanding jobs can be filled by the skillset of those holding jobs that contracted. And that is of course the great challenge for workers in the future. Change brought about by pandemic, or indeed by other forces, demands agility by workers, business and the government.

The fact that the unemployment rate has recovered to its pre-pandemic level is evidence of the ability of Australian workers to adapt.

However there are other lessons from the pandemic.

For years, if not decades, we Australians have convinced ourselves that we should focus on what we do best – mining, housing, lifestyle – as part of an overall strategy that delivered unbroken prosperity.

However the pandemic has demonstrated that we cannot always rely upon the free flow of goods, services and people (eg tourists, students, workers, migrants) between countries. That was always a flawed assumption in a world of rising geopolitical tensions.

We need to be more self-sufficient throughout the 2020s and beyond.

We need to be adding value to agribusiness product in big cities and in regional centres. We need to retain key capabilities like the ability to refine oil, to manufacture face masks and PPE, to develop and manufacture pharmaceuticals, and the ability to manufacture defence equipment and ordnance.

But the pandemic and the border closures have exposed another fault-line. We need to be better equipped at and more focused on developing key skillsets like those delivered by the TAFE system. We need more essential workers, more tradies, more graduates in engineering, technology, mathematics and science.

The great realisation that is now upon Australian business if not the Australian people is that even so-called clever countries need plumbers, electricians, carpenters as well as shelf-fillers and other essential workers to ensure our ongoing independence and quality of life.

The property industry has a role to play. That involves adapting to new consumer trends and responding innovatively to the demand for skilled labour. Governments are undertaking large-scale infrastructure projects that will be delivered by property-type skills.

The next decade was always going to involve a trajectory shift because of the baby bust. But shallow labour pools cannot and should not be simply filled by cherrypicking foreign labour. That strategy leaves us dependent upon others or at least upon free access to foreign labour markets.

We need better local capabilities to deliver the skills required and to offer more Australians skilled work opportunities. We have a history of responding well to global calamities like war and depression; we’re regarded as a safe haven; migrants and others will want to come to Australia in the 2020s.

We are a fortunate nation with resources, room to move, good relations with like-minded nations.

We offer a good quality of life to a great many.

But we do need to evolve and adapt to our changed circumstances. Perhaps the property industry can lead the way by helping envision an even better version of the Australia we left behind in the pre-pandemic world.

Bernard Salt is executive director of The Demographics Group; research by Hari Hara Priya Kannan

It is an issue that was always going to be of concern for government and business this decade.