Labour force of the future: skilled, agile and upbeat

More storemen, more mail sorters, more delivery drivers – the pandemic has been a globally significant agent of change. Our jobs, and who gets them, have been altered forever.

There are several lenses through which the future of work might be viewed.

There are issues around automation (including digitisation) and access to skills and labour as well as straightforward demography: are there more young workers coming through than old workers retiring?

And then there’s the vexed issue of work from home and how it might be incorporated into the way Australians work in the future.

-

Skills and jobs

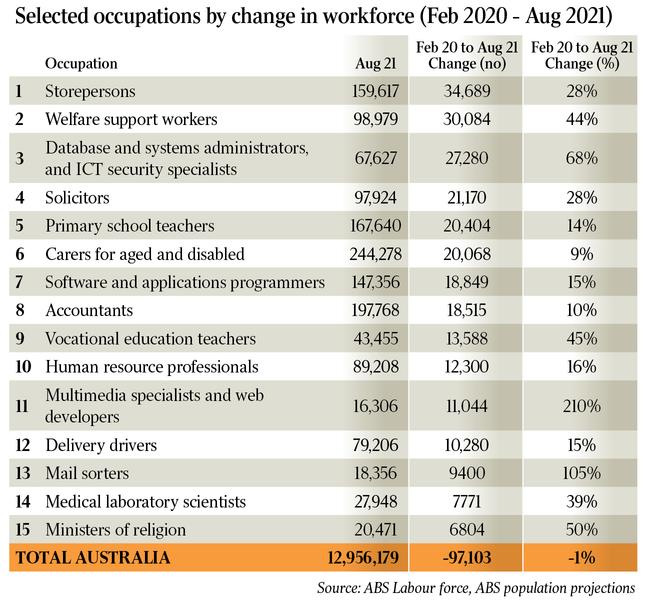

The Australian Bureau of Statistics tracks the workforce via a quarterly survey which estimates the number of workers in each of 450 occupations.

By comparing estimates between February 2020 (pre-pandemic) and August 2021 (Melbourne and Sydney lockdown) it is possible to see, over 18 months, how employment changed.

I have selected 15 “growing jobs” to showcase where I think the future of work is headed. It is important to remember these figures are assessed by survey so they should be read in context and across a time series.

However even with these limitations this dataset provides a glimpse into the future of work.

Some of the fastest-growing jobs during the pandemic have been in unskilled and low skilled work. Here is an employment shift that reflects a fundamental change in consumer behaviour.

The rise in storemen (up 35,000), delivery drivers (up 10,000) and mail sorters (up 9000) confirms retail spending has shifted online, requiring more workers in logistics and parcel delivery.

This trend was in place before the pandemic; it has been mightily boosted by the WFH movement and post-pandemic is likely to revert to an above-trend share of the entire retail market (ie shops plus online).

The digitisation of the workforce continues with job growth in many aspects of technology prompting requirement for database and system administrators (up 27,000), software and applications programmers (up 19,000) and multimedia managers and web page designers (up 11,000).

To some extent growth in these tech jobs reflects the impact of the pandemic which shifted businesses online.

However, I suspect many of these adaptations will be carried forward as businesses pursue a greater online presence.

There are now many more jobs in care and support including aged and disabled carers (up 20,000) and welfare support workers (up 30,000).

And continuing the care theme, there has been a surge in the number of people claiming to be a minister of religion (up 7000).

There is sure to be some sampling error in these figures (which may be corrected next quarter) but the strength of the surge suggests the pandemic has triggered some to think about life’s bigger issues.

And then there’s increased demand for knowledge worker jobs such as accountants (up 19,000), solicitors (up 21,000) and human resource professionals (up 12,000).

All this churn and adaptation caused by the pandemic creates demand for skills in law, finance and people management.

Pleasingly there has been growth in demand for primary school teachers (up 20,000), the demand for which is tied to population growth, as well as for vocational teachers (up 14,000). Indeed, even clever countries need plumbers, electricians, carpenters and other technical doers.

On the negative side this dataset tracks shrinking demand for truck drivers (down 36,000) and forklift drivers (down 12,000). The post-pandemic world hinted at by these figures suggests supply chain disruption: fewer warehouses trucking goods direct to shops; more (robot-enabled) fulfilment centres using delivery vans (and eventually drones) to deliver product to homes via routes determined by algorithm. And where, in time, even the delivery vans could be autonomous.

Other jobs contracting during the pandemic include bank workers (down 16,000) and secretaries (down 6000). To be fair these jobs have been in decline for more than a decade and largely because of the effects of new technology (eg online banking) and changed work practises.

Secretaries are now more likely to be called something such as executive assistant or office manager although even these titles are losing currency. What is required is a non-deferential title for valued workers with general skills and who interact daily with in-situ and at-home co-workers.

The lesson from all this isn’t so much the need for skills and training – that need has been evident for decades – it is more that post-pandemic workers must adapt to emerging work opportunities.

No job is immune to change; the pandemic has been a globally significant agent of change.

-

Demographic outlook

The Australian workforce currently comprises 13 million workers plus a further 700,000 unemployed (5 per cent) in the labour force. About 64 per cent of the population aged 15 and above participate in the workforce.

The ABS developed (median) projections of the Australian population in 2018 which showed net growth of four million between 2021 and 2031.

We have taken the (rising) labour force participation rates by cohort over the period 2011-2021 extended to 2031, applied these to a rebased projected population, so as to derive an estimate of the net change in the labour force in the post-pandemic era (see bar chart).

In a direct comparison between the labour force of today with an estimate of that in 2031, it is evident there will be more workers in every cohort.

This will be effected by cohort growth (ie local population ageing), by increased participation (eg women remaining-in/returning-to the workforce), by net overseas immigration (and which may be moderated from the levels assumed by the ABS in 2018).

-

My take-outs are:

● Even with contracting participation rates for the 15-24 cohort (eg studying, training) there’s still more young workers available in 2031 than in 2021;

● The combined effects of late Baby Boomers (born late 50s/early 60s) pushing across the 65-line, plus an increased propensity for this lot to remain in work (as evidenced by increased participation) delivers a deepening pool of Over-65s to draw from across the 2020s.

● And, courtesy of Whitlam’s fee-free tertiary education in the 1970s, many in this cohort are university-trained knowledge workers;

● The growth cohorts are the late 30s and 40s caused by a reverberation of the baby boom, the so-called Millennial generation (1983-2001) pushing deep into that stage of the life cycle where there is both scope for and need for career advancement;

● The soft bits of this projection, in my view, relate to workers in the 25-34 cohort (ie first home buyers) which may be diminished by post-pandemic cutbacks in immigration and by the switched preferences (eg from Australia to Canada) of foreign students who might otherwise tumble into the Australian labour force.

Issues around the future labour force aren’t so much tied to demography — growth appears to be assured even at moderated immigration rates — they’re more to do with producing the right skillsets in the right locations across Australia.

A big part of this issue relates to pipeline planning by universities and vocational colleges that are hopefully looking to boost their student throughput in the 2020s. If there’s one thing the pandemic has taught the workforce it’s the need for skills.

Another part relates to offering the right incentives (to attract seasonal/backpacker workers), to delivering competitive wages and conditions, and to facilitating a workforce that is mobile (acknowledging that not all workers with the right skills can relocate).

There is also an issue, I think, in changing parental attitudes towards career development. Not every secondary school student is suited to, or wants to attend, university.

Just as during the pandemic we revalued the role of the supermarket shelf filler — they’re valued, essential workers — we need to rethink our attitudes towards technical/vocational work versus knowledge work.

The pandemic taught Australia a valuable lesson. We were very pleased with our pre-pandemic, global, just-in-time supply chain that enabled us to focus (cleverly, we thought) on what we do best: delivering housing, lifestyle and quality of life.

This thinking made us dependent upon overseas manufacturers.

But it also made us dependent upon being able to cherrypick skilled workers such as welders from Manilla, data scientists from Bangalore, and chefs from Ireland.

We will still need overseas skilled workers in the 2020s and beyond.

Just as we will still need overseas- traded goods.

However, in order to assure our future prosperity should use this control-alt-delete moment to strengthen our skills training capabilities, and to broaden our collective view of the preferred career pathway.

Bernard Salt is executive director of The Demographics Group; research by Hari Hara Priya Kannan

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout