The International Monetary Fund gives us powerful economic data to understand wealth distribution across the world.

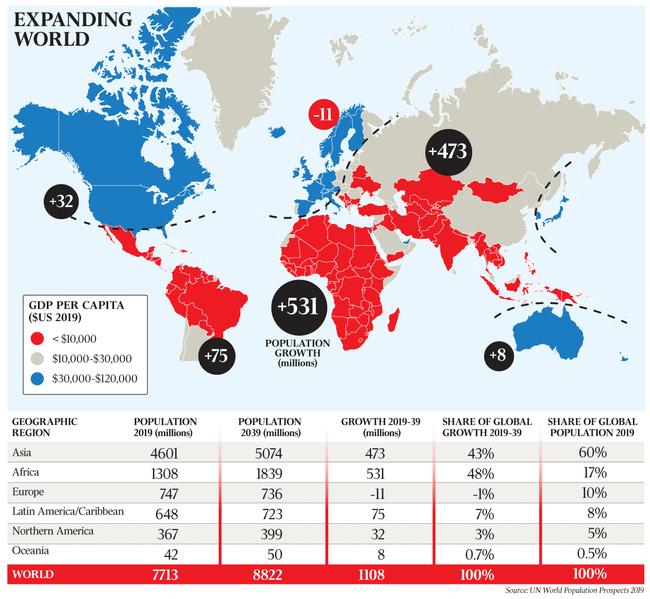

We will stick to the basics and roughly divide the world into rich countries (where gross domestic product per capita was over $US30,000 in 2019) and poor countries (under $US10,000).

The world map shows four major global economic fault lines where rich and poor collide.

The first lies between rich North America, where GDP per capita is at $US49,200, and Latin America (Central America $US5600 and South America $US8600).

The second fault line separates rich Asia (Japan $US41,000, South Korea $US31,900 and Taiwan $US25,500) from poorer but up-and-coming Asia (China, for example, comes in at $US10,200 with much room to grow).

The third separates Western Europe ($US42,900) from Africa ($US1700 for Sub-Saharan Africa and $US3500 for North Africa), the Middle East ($US12,100) and even Central Asia and the Caucasus ($US5200).

The fourth major rich-poor fault line separates Australia and New Zealand ($US53,200) from our neighbours in the north (Papua New Guinea $US2500 and The Philippines $US3300).

Let’s think about these four economic fault lines in terms of global migration patterns.

People migrate because they are either pushed or pulled to do so.

If the situation in a country is so bad that people fear for their lives and can’t see how things could ever look up again, they become desperate and risk dangerous journeys (often through illegal channels) — they quite literally have nothing left to lose.

In Australia, only a tiny proportion of migrants — refugees — were pushed to Australia. We run a skill-based migration program, meaning our government decides on a number of migrants that we allow into the country every year, and then give these spots to migrants who have the exact skills that our economy demands.

Your British co-worker, your Kiwi mechanic or your Malaysian accountant weren’t desperate to leave their homeland, but were pulled towards Australia by career opportunities or preferable weather.

Countries don’t experience big outflows of population if it’s seen as physically safe, growing economically and a place where the effort you put in improves your lot.

The UN Population Division in New York just updated the world’s most exciting and comprehensive population dataset — the World Population Prospects 2019. The WPP provides us with population projections by country until 2100.

Focusing on the big-picture narrative, we will look out 20 years into the future until 2039 and focus on population figures by geographic regions. By 2039, the global population is forecast to reach 8.8 billion.

Let’s explore the surprising forms the addition of 1.1 billion people over the next 20 years will create in the fortunes of the Australian property and infrastructure market.

The general population pattern is very clear. We see strong population growth on the poorer sides of the fault lines, and slow growth or even shrinking populations on the rich sides.

Africa currently houses 17 per cent of the global population but is forecast to take up 60 per cent of all global population growth over the next 20 years. That’s another 531 million people (or about the entire EU). If the African nations stay peaceful, continue to educate their young and growth their GDPs as the IMF forecasts, all will be well.

If that’s not the case, we might not see a weakening of the migration pressure towards Europe over coming decades.

Similar issues will play out along the other fault lines. What if millions and millions of people see their economies stagnate or go backwards? They are all hooked up to the net via smartphones and know where opportunities might be better.

Of all the fault lines, the Australian one is by far the easiest to manage from a policing point of view. Also, our northerly neighbours are generally growing their economies, which means that financial desperation is relatively small and they are reasonably stable politically.

But how does all this affect the Australian property sector?

Big players — think of a Canadian pension fund or, say, the Norwegian sovereign wealth fund — have billions of dollars under management. Their analysts look at the same data we examined and might conclude that Europe will struggle financially with border issues related to migration from Africa, that Brexit will slow economic growth in the European Union, that trade wars hurt the US economy and unstable regimes across the world might tumble.

The more these big global investors view the world as unstable, the more they will look to the remote, stable corners of the globe as financial safe havens. Sometimes the tyranny of distance can be beneficial.

Any kind of assets that can be purchased will be seriously reviewed by the big global investors: “We’ll take 38 Australian marinas, 92 private childcare centres along the growth areas of the eastern seaboard. While we are at it, do you have any big toll roads we can grab, please?”

Our capital cities (and Auckland, for that matter) have been adding population at massive rates over the past two decades while our infrastructure investments weren’t even close to keeping pace.

Come what may, we need about two decades of highly elevated infrastructure spending in our largest cities to keep people and the economy moving.

We know how expensive and difficult to finance such big infrastructure projects are. In a surprising twist, unstable conditions in Africa, slowing growth rates in Asia and border control issues in the US might very well lead to a lot of international capital flowing into Australia.

To capture and make use of this money, we must have large-scale infrastructure projects in the pipeline backed by both sides of politics. Over the next years, we really wouldn’t want to miss out on global capital flows simply because we can’t decide which pieces of infrastructure should be built and which ones shouldn’t.

Simon Kuestenmacher is director of research at The Demographics Group.

By combining two exciting big-picture datasets, we learn why powerful international property investors might be doubling down on their investments in Australia very soon.