Courting foreign students in a post-Covid Australia

The education ‘business’ is vital to the nation’s economic and social fabric.

One of the biggest issues arising from the pandemic is the impact that border closures is having on the international student market. Many people from overseas associate Australia with sunshine and beaches.

Indeed, Aussies are well known internationally for their friendly manner and easygoing attitude. So it makes perfect sense that Australia is an attractive destination for international students.

However, add in the fact that Australia is also an English-speaking country, and that it offers tuition at affordable fees, and it’s easy to see why this country ranks as one of the most preferred by international students.

What are the numbers?

According to UNESCO’s Institute of Statistics, Australia was the second leading country (after the US) in international education in 2018. Seven Australian universities are currently ranked in the world’s top 100 by UK-based publisher Quacquarelli Symonds (that is ANU, Melbourne, Sydney, UNSW, UQ, Monash, UWA).

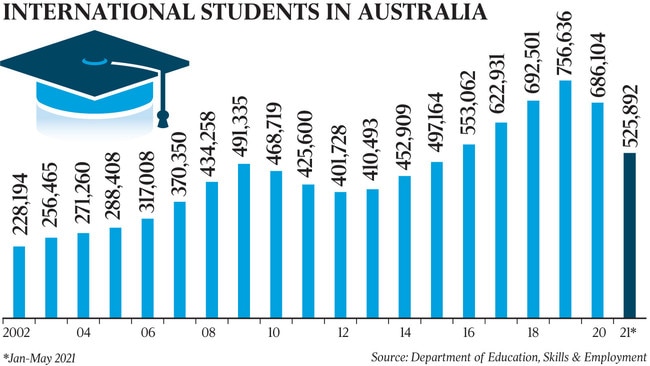

Australia recorded strong growth in international student numbers for two decades leading up to 2020 (see graphic 1).

The federal Department of Education, Skills & Employment releases data every month showing the number of international students, enrolments, and commencements in Australia.

There were 527,000 international students enrolled in 590,000 courses in May 2021. Some 54 per cent of these students were enrolled in universities while a further 37 per cent were signed up for vocational (trade) courses. The balance comprise students in secondary schools and short-term language courses.

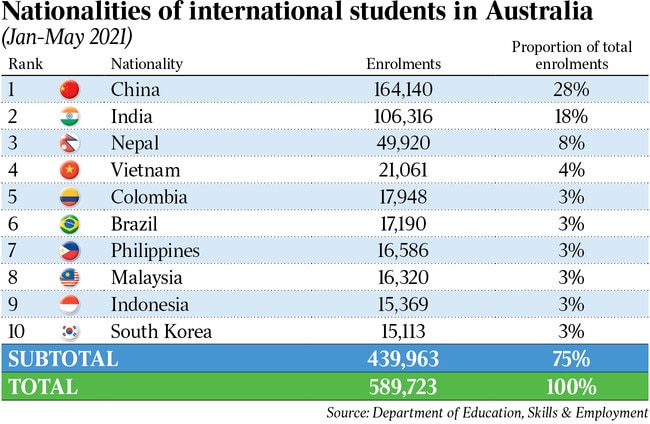

China and India accounted for almost half (46 per cent) total enrolments. China led with 164,000 followed by India (104,000), Nepal (50,000), Vietnam (21,000) and Colombia (17,948).

Just 10 countries accounted for 75 per cent of total enrolments (see graphic 2).

WHERE ARE STUDENTS LOCATED?

There is no publicly accessible data on the residential location of international students outside the census.

However, at the 2016 census Australia’s (full-time) international students lived close to (or on the grounds of) universities and often in purpose-built apartments or in share houses.

The majority (62 per cent) of foreign students lived in rented accommodation at that time.

The biggest clusters were concentrated in the Melbourne CBD (11,000), in Sydney’s Haymarket (6000), in the Adelaide CBD (3000) and in Brisbane’s St Lucia (3000).

In response to border closures the number of international students in Australia dropped from 686,000 in December 2020 to 527,000 in May 2021 which was a decrease of 159,000 or 23 per cent across the five months following last year’s graduation ceremonies.

It is likely that these numbers will fall further in the coming months with border closures still in place (restricting inflowing students) and considering the number of students likely to graduate in December.

According to Overseas Arrivals and Departures data released by the ABS, the number of persons who arrived in Australia for educational purposes between January and May this year, totalled a mere 1660. The number that arrived in the same period in 2019 was 299,750.

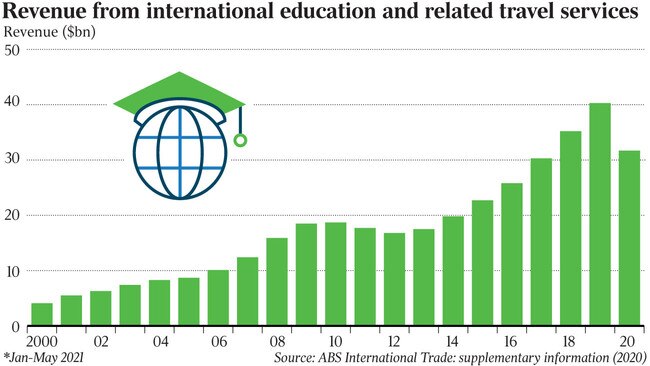

International students contributed $40bn to the Australian economy during calendar 2019, according to the ABS (see graphic 3).

In 2020 this contribution dropped to $31bn.

However, throughout the 2020 calendar year many students remained in Australia to complete their studies and left after graduation. With virtually no student inflow in the current year the contribution of the student economy to Australia is likely to fall even further in 2021.

And it’s not just universities that derive benefit from international students.

Apart from tuition, students pay for their own private health insurance and living costs – including property rental – which all contribute to the wider economy. Students go to cafes, watch movies, do shopping, and visit places boosting small business.

International students create demand for rental accommodation in major cities and especially in university precincts. Many purpose-built residential towers rely on international students.

Plus, visiting friends and family members help drive tourism and related activities within Australia. (My parents and extended family spent two months in Australia when I graduated in 2019.)

Impact on the workforce

In 2018, the spending of international students supported 240,000 full-time jobs in the Australian community, according to the federal Department of Education and Training.

These are jobs based out in the community rather than in academia or its administration. Student’s spin-off spending helps creates jobs for chefs, waiters, taxi drivers, shop assistants, real estate agents and workers in construction and tourism.

There are workforce benefits that flow from international students when they remain in Australia for work experience.

International graduates inject skills into the workforce at nil cost to the taxpayer because their education is self-funded. Graduates also pay the same taxes as an Australian resident, but they do not receive benefits such as Medicare.

Graduates who remain in Australia consume services, pay rent, buy food, take out private health insurance which all contribute to the Australian economy.

According to the Department of Home Affairs some 80 per cent of students leave Australia once their education is completed. Some 16 per cent generally transition to permanent residency. Based on these figures it is evident that international students and graduates do not take locals’ jobs.

On the contrary, the number of jobs filled by students is a fraction of the job opportunities they create.

In a policy designed to encourage students to enrol for additional courses, the Department of Home Affairs announced in mid-2020 that students who enrolled in online classes were eligible to apply for a post-study temporary graduate visa.

Prior to the closure of international borders this visa required full-time study and was especially prized by students because it allowed graduates to work for two years after graduation.

However, the transition to online learning is not popular with students.

According to research completed by the Department of Education, Skills and Employment, between January 2020 and March 2021 there were 127,000 deferred enrolments by 92,000 international students, over two-thirds of whom were based overseas during this period waiting for the borders to reopen.

By the end of March 2021, only 39 per cent of these students had recommenced their studies (mostly online) or finished their studies altogether. And as for the remainder, it was assumed that they would (or might) recommence their studies when travel restrictions were lifted.

However, the danger is that deferrals and postponements may prompt international students to look elsewhere.

Especially as study destinations like the US, the UK and Canada are now fully opened to international students.

This makes the Australian strategy of encouraging students to complete their studies online appear less than competitive in a global education market.

The way forward

One way to bring international students to Australia would be to accept only those who were fully vaccinated and who provided evidence of a negative test upon arrival.

Students could then be quarantined in the property industry’s purpose-built student accommodation, thus preventing hotels from being overloaded.

And while the number of students from China has been declining, Australia now has a greater level of access to the European market with Brexit changes requiring students to pay full tuition in the UK.

Canada is a natural competitor to Australia in this market. The Canadians offer a pathway to permanent residency based on a points system like Australia. Improving the opportunity for permanent residency, such as prioritising applications from onshore graduates – gainfully employed and making a social and economic contribution – would encourage even more students to apply to study in Australia once the borders reopen.

Offering residency to onshore graduates would also help redress the current skills shortage. After all, this is a workforce that has been trained and skilled to Australian standards making them an ideal choice to plug the skills gap.

It must also be remembered that graduates returning to their home countries once their two-year visa expired would exacerbate the existing shortage of skilled workers.

Why not capitalise on this valuable human resource by offering residency to those with the required skillsets?

Outlook

Although the outlook for the balance of 2021 seems bleak, if we can vaccinate most of the population by the end of the year, paving the way for a reopening of the international borders in 2022, it may be possible to avert even bigger losses in the education and related sectors. Australia has long stood apart from other nations in welcoming overseas students and skilled migrants.

By deftly recapturing the international education market, Australia could lessen the skills shortage, inject much-needed flow-on spending to the broader economy, revive the inner-city apartment market and, via the soft diplomacy of welcoming students to the Australian way of life, create friends, social ambassadors, allies and potential business partners scattered throughout Asia.

When you add everything together, rebuilding the international student market is critical to the recovery, the skilling, and the regional positioning of Australia in an uncertain post-Covid world.

Hari Hara Priya Kannan is a data scientist at The Demographics Group; she is a former international student.