2022 outlook: three property trends to look out for

The pandemic will have a number of effects on where we live and help trigger massive change in our lifestyles.

The pandemic has effected (or accelerated) a shift towards owner-occupied residential property, home improvement, working from home, online retail, customer autonomy, local manufacturing, offsite storage, industrial space, warehousing & logistics centres and my personal favourite, hyped demand for regional and lifestyle property.

And so of these changes which, in my view, have the greatest social and cultural impact on the Australian people? And how will they play out in 2022? Let me take you through my thinking.

Manhattan Effect … essential labour displaced

Two years of closed borders have changed the behaviour of Middle Australia, which now views international travel as a risk as opposed to an aspiration to be savoured and paraded among friends and colleagues.

Maybe all those frustrated Australian travel budgets are being redirected to lifestyle property in the form of a Byron bolthole or similar. Move permanently to “the weekender” or simply buy something more permanent far from the madding (and infected) crowd. This certainly seems to have been the Melbourne narrative early in the pandemic.

If this has been a consequence of the pandemic, then labour-dependent businesses within the weekender orbit of capital cities would start to suffer from the so-called Manhattan Effect, where essential workers can longer afford to live in the locale in which they deliver their essential labour.

Cleaners, cooks, gardeners, sanitation workers, waiters, labourers and others doing what needs to be done to make a city work are flung out, as if propelled by a centrifugal force, to the outermost reaches not of New Jersey but of the Northern Rivers, to the Noosa and Gold Coast hinterland, to the edges of Geelong, Wollongong and Newcastle. And indeed from such places essential workers must now commute to deliver their services.

The social structure of the lifestyle coast is changed by knowledge-worker invaders Zooming-in from real estate that might have been previously let to backpackers, seasonal workers, transients and others who make up, or who made up, the lifestyle-coast’s essential worker workforce.

A pandemic-inspired jump in values is great news for (coastal) property owners but less so if it comes at the cost of displacing essential workers.

CBD revival … not quite there

Back in the big cities another narrative has been changed by the pandemic, much to the chagrin of the property industry.

The initial work-from-home edict delivered in April 2020 has spread, like a virus, across the nation and even to the hermetically sealed city of Perth where workers, I am sure, would argue that if the Melbourne office gets this option, then so should we.

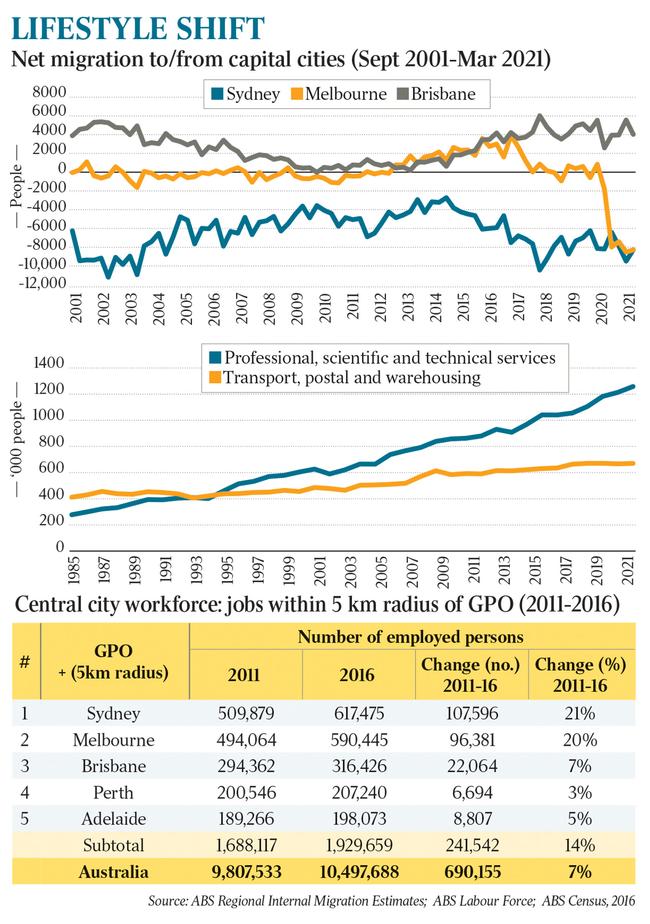

The question for 2022 is the extent to which workers will return CBD offices. Without the effects of pandemic perhaps 700,000 jobs would have huddled within 5km of both the Sydney and Melbourne CBDs by 2021 requiring a commute and supporting an entire ecosystem of local businesses from sandwich bars to drycleaners.

As the effects of the virus recede, and as work-from-home fatigue sets in, there is likely to be relief if not outright exhilaration that the CBDs are recovering, enlivening, awakening from their enforced and paralysing slumber.

The fact is some work, perhaps most work, is indeed far more effectively completed in a CBD office environment drawing upon the collaborative support of colleagues and management. Proof of this fact will be evident later in 2022 as the CBD’s returning workforce passes, say, the 85 per cent mark of pre-pandemic occupancy levels.

However the possibility is the aggregate returning workforce may not (for some time) exceed, say, 90 per cent of pre-pandemic levels.

This “holdout” proportion will vary by city, by business sector, by building. Think about this: is it likely that 100-per-cent of the pandemic’s work-from-home community will return to commuting as soon as possible?

This office-return hesitancy will apply, I think, to workers whose commute starts from places like Penrith, Cranbourne and Caboolture. (And not from places like Balmain, Fitzroy and West End let alone from places like Point Piper, Toorak and St Lucia.)

The 10-15 per cent gap in this return-to-the-office outlook is largely comprised of workers whose work isn’t connected into the functionality of the CBD: consultants, contractors, low-paid workers who would daily weigh the cost of the commute versus the benefit of working in the city.

Not every worker works to impress their boss, to build the case for a promotion, to socialise with their co-workers.

To some workers, a CBD job is a means to support a family and that enables other, far more important choices to be made, such as allocating time and resources to family, sport, friends, church.

Retail reimagined … apps and online boosted

We are an aspirational nation predisposed to spending much of what we earn, and more, on lifestyle, property, consumer goods and travel.

We regard housing not so much as an essential service but as a symbol of our social and economic progress.

The pandemic has increased the national dwell time in the family (and household) home. The more time spent in any building the greater the tendency to spend (eg airport duty-free). Early in the pandemic Australians spent big on home appliances, furnishings, technology and furniture. I understand demand for artworks also boomed. Much of this net additional spending has been done online as opposed to instore. Australia’s biggest retailers now offer click-&-collect as well as home-delivery services. Even the way retailers (and others) interact with customers has changed: there’s less emphasis on call centres; more emphasis on DIY apps.

Australians were conditioned by the pandemic to be far more self-sufficient with regard to navigating rules, regulations and permits using QR codes and facilitating proof-of-vaccine downloaded to an Apple Wallet.

The customer relationship is changing. The (offshore) call centre emerged as a new concept in the 1990s, however by the 2020s a new iteration has evolved, courtesy of the pandemic: indeed, it’s apps everywhere. Despite management’s feel-good rhetoric about “putting the customer first” many businesses seem to be doing whatever they can to dissuade customers from chewing up time speaking with someone in the business. Restaurants are increasingly on board with an app-versus-phone booking system.

The same logic applies with doctor’s surgeries, airlines, supermarkets and government departments. Don’t speak to us; look it up yourself on a website.

In relation to retail this means there’s less need for product to be shipped to shopping centres and greater need for product to be shipped direct to customers.

The impact on property is direct: less instore retail turnover, more warehouse space and workers. I think the way this will play out in retail is similar to the way work will change in a post-Covid world.

Online retail targets specific products with rifle-shot accuracy: books, technology; appliances; products with known qualities and clear specifications.

The work-from-home movement preferences workers and jobs where the deliverables are known, where this is no real requirement for direct supervision or collaboration, and where financial and/or contract relationships are set in place.

In both cases the post-pandemic world shifts some (targeted) transactions from the office and shop and to the home and warehouse.

The warehouse transforms into a bigger, sleeker more automated facility that is given a groovy new name: this isn’t a warehouse it’s a fulfilment centre. The office (and the CBD) morphs into a place of learning, collaboration, training, client schmoozing and celebration.

The boring bits of work — quietly drafting a report, developing a legal opinion, completing an audit — are outsourced to the family home.

The process-driven aspects of shopping — such as buying new printer cartridges — are extricated from the retail expedition. Bit by bit the nature of CBD office work, and shopping, changes.

Conclusion

The pandemic has been too big and too longstanding for it to not impact consumer and worker behaviour. It has forced the adoption of innovative technology; it has probably helped trigger a shift in key geopolitical settings.

Covid-19 may not have been a war but for decades to come it will serve as a breakpoint in the narrative of Australian life. There is no “getting back to normal”. We’ve come to far; we’ve learnt new skills; we have new priorities: arguably there’s a new generation in charge.

The property winners in 2022 and beyond will be those who don’t maudlinly yearn for the past but who boldly and with an outrageous sense of self-confidence embrace the future.

Bernard Salt is executive director of The Demographics Group; research & graphics by data scientist Hari Hara Priya Kannan.

This might seem like an odd perspective to take but I don’t think the really big issues in property are in question.