Octopus has created a revolutionary new service platform that has the scope to dramatically change the way energy is managed at the retail level.

Calabria will take a 20 per cent stake in Octopus for $507m, becoming the first outside investor since Greg Jackson started the company four years ago.

The big end of town may be jumping into bed with a disrupter, but it’s one that has established its credentials as a fast-growing UK retailer, and Origin is buying a stake as it potentially expands globally.

Platform economics is the prevailing path to corporate value today, as shown by seven of the world’s 10 most valuable companies, and McKinsey argues 30 per cent of global activity takes place on digital platforms.

Octopus is not in the same game as Apple, Amazon, Google, Facebook et al but is akin to the Ocado joint venture Coles has signed that will revamp its online operations when launched in 2023.

Many will relish the fact that Origin is focusing its efforts on its retail division, as exposed to its costly APLNG joint venture in Gladstone. Of course, there is still Gladstone and the Beetaloo prospect in the Northern Territory that is on hold pending the reopening of the project after the COVID-19 lockdown.

It’s a big call and it must be said former AGL boss Andy Vesey promised much the same when he spent $200m revamping his systems a couple of years ago. Alinta’s Jeff Dimery looked, but has also gone his own way with his Core network upgrade.

Origin retail boss Jon Briskin and strategy and commercial chief John Bowie have been working on the project with Jackson for the past 12 months.

In theory the end result should be a better and cheaper energy retail market in Australia, which is something everyone from prime ministers to ACCC bosses down have been screaming for.

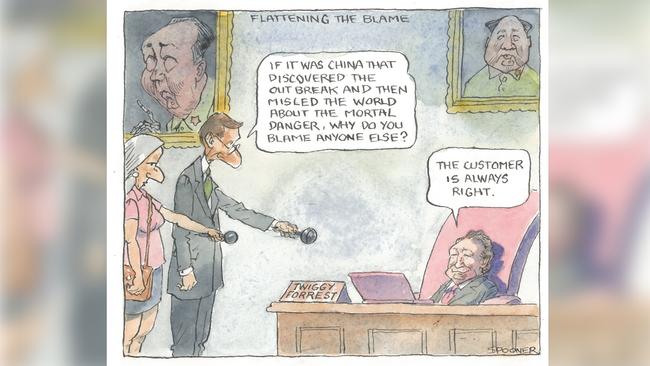

Calabria talks more about better customer service and in the process a lower churn rate for him, which also cuts costs.

The energy utilities talk about costs to serve and Origin already claims market leadership for its 3.8 million retail customers at $169 per customer a year, compared to AGL at about $180 a customer.

Cost savings already in train will take that down to $145 a year and, when it transfers across to Octopus’s Kraken software, it will fall to $120 a customer.

Part of that fall is explained by the saving of about $80m a year in licensing fees paid to SAP.

Octopus has about 5 per cent of the UK market but is growing fast, with a recent deal with German-based utility EON.

The Octopus model changes the way you deal with your local utility, which is now based around your meter, but in future will be based around the customer, which means if you buy gas and electricity from Origin rather than talking to Fred at Origin about electricity and Jane about gas you will talk with just one person about all your energy needs.

Come the revolution, when the distributed grid takes hold due to your solar rooftop panels, that will all be accounted for in the same system, and when you move home it will be two clicks to the new address rather than the complicated system of meter reads today.

The back-end systems obviously enough are also grand harvesters of data about what energy you use and how, which is used in part to deliver better service.

The integrated platform also delivers energy through a flatter corporate structure, which also brings down costs

It has also won favour in the UK because it uses green power.

The cloud-based platform benefits the more energy users are on it, which means volumes also make it more competitive, but whether it delivers cheaper electricity remains to be seen.

In part, that is due to other factors and it is encouraging to note the forward futures contract is now selling at $42 a megawatt hour, which is down from $110 an hour three years ago.

This is a consequence of demand falling, plenty of supply and, other things being equal, should translate into cheaper electricity in the next year or so.

Separately, the ACCC has granted interim authorisation for the retail industry to talk to each other and the Australian Energy Council about financial relief packages. The ACCC is open to attend the meetings and the aim is to try to use peer pressure to get better offers sooner.

Staying informed

Regulators should be encouraging companies to give more guidance than less, but as ABL partner Jonathan Wenig notes, ASIC and ASX are virtually discouraging forward-looking statements.

Wenig argues the US SEC by contrast supports forward-looking disclosure offering a safe harbour for good faith statements made with the appropriate language. Far better for investors to hear more about the range of scenarios before the board than less.

ANZ copped the ire of analysts by being less than fulsome in its disclosure of the impact on risk-weighted assets based on different economic outcomes.

The trouble facing all boards is that, come the end of September when an array of government subsidies are halted, just how the economy reacts is anyone’s guess, other than concluding not well.

As Wenig argues, it is better to have more information issued cautiously than a caution-induced vacuum.

Hopes on reform

The federal government’s COVID-19 assistance package runs out at the end of September, at which stage we will know just how bad the economy is.

This is when the much-vaunted reform package is meant to take centre stage and business is hoping the revamped National Cabinet will deliver the promised structural reform.

This is a big test for Scott Morrison to see how much is talk and how much action.

On tax, business argues we have had all the reviews necessary to deliver comprehensive reform, but if the aim is to simply restart the economy an investment allowance-type stimulus is seen as the most targeted stimulus.

None of which is to stop actual reform by way of a comprehensive structural overhaul, which could in theory be agreed to and outlined in the budget, but not take effect for a year or two.

Origin’s Frank Calabria is from the big end of town, one of the big three energy giants, but he has joined forces with a UK-based disrupter, Octopus Energy, in a bold attempt to shake up the retail market in Australia.