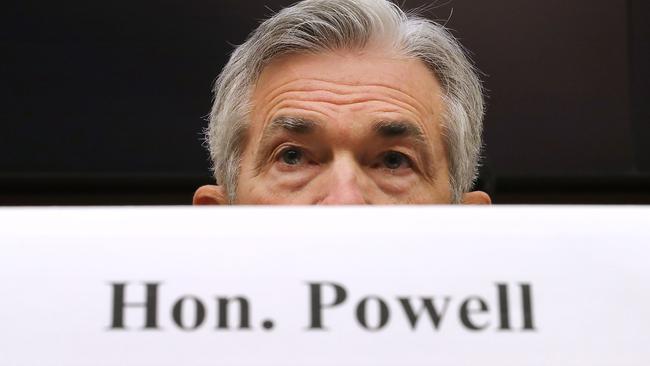

Is new Fed chair Jerome Powell a friend, or threat, to markets?

Disconcertingly for markets, new Fed chair Jerome Powell seems unconcerned about recent volatility.

After climbing nine per cent from the start of the year to January 26 — from record levels — the US market has since slumped nearly 8.5 per cent, with the one per cent fall overnight putting a full stop to the biggest monthly fall in two years.

Moreover, after a year which was one of the least volatile in US equity market history, volatility abruptly resurfaced in February, including a quite dramatic 4.1 per cent single-day fall on February 5 as the VIX index, which reflects investor expectations of volatility, more than doubled in an instant.

From late January to the second week of February the market was down more than eight per cent before bouncing back up by more than 7.5 per cent and then tailing away by nearly 2.5 per cent in the last couple of days of the month. Levels of intraday volatility have also spiked recently.

Those gyrations, unseen last year, are at odds with the performance of the US economy and the confidence of US businesses and consumers — and the US Federal Reserve Board — in its outlook.

In fact it is a view that the economy may be growing too strongly that has ignited the volatility in both equity and bond markets and it was the bullishness of new Fed Reserve chairman, Jerome Powell, that triggered this week’s flare-up and selldown in markets.

Testifying before Congress on Tuesday Powell said the US economy had been stronger so far this year than he had expected in December and that he and his fellow Open Market Committee members would take the better-than-expected data into account at their next meeting, scheduled for the 20th and 21st of this month.

It was that comment that led to a market convulsion on Tuesday, with equity and bond investors interpreting it as a signal that, rather than the three 25 basis point rate rises they were pricing in for 2018, there might well be a fourth.

With the Trump administration’s deficit-funded tax cuts flowing and synchronised growth in the developed world economies boosting US exports “some of the headwinds the US economy faced in previous years have turned into tailwinds,’’ Powell said.

He was, disconcertingly for financial markets that in the post-crisis period regarded the Fed and other key central bankers as underwriters of their risk, unconcerned about the recent quite violent swings in the markets. Despite the volatility, he said, financial conditions remained accommodative.

The Powell Fed, after four years of well-flagged and cautious policies under Janet Yellen, is an unknown quantity. The tone of his comments were more “hawkish’’ than the market has come to expect from the Fed chairperson.

With the Fed now normalising US monetary policy — gradually lifting rates and starting to shrink a balance sheet full of the $US3.6 trillion or so of bonds and mortgages acquired during its three quantitative easing programs — Powell might well see the markets’ volatility as a positive.

The challenge for the Fed as it began to normalise its policy wasn’t only to do it without choking off the healthy growth rate the US has been experiencing but to find a way to wean the markets off the notion that the Fed will always to intervene to, in effect, protect investors against significant loss — that the Fed’s fear of a financial market meltdown provided insurance for investors.

It was that confidence that the Fed would help out in a crash that removed volatility and the pricing of risk from markets and has seen the value of financial assets, and real property, inflate around the world on the back of the central bank-driven ultra-low borrowing costs in the developed world.

The Powell Fed has the conventional challenge of responding to the prospect that the Trump tax cuts, its aggressive deregulation program and, perhaps, the administration’s infrastructure plans, could pour oil into an economy that is already quite hot and already operating at levels that aren’t that far off capacity.

Its plan is for a continuation of the gradualism that has been its strategy since the cycle of rate increases began in late 2015 but its hand would be forced if US inflation were to pick up too quickly and strongly.

A secondary objective for Powell would be to manage the normalisation of rates while maintaining solid and sustainable economic growth rates without scaring the markets into a meltdown that would, given the impact on investors and companies, have real wealth and confidence effects.

Whether it is within equity, bond or property markets, an enormous amount of paper wealth has been created — and borrowed against — in the post-crisis era by the lengths to which the central banks went to avoid a financial system collapse.

Somehow they will need, if there isn’t to be another systemic crisis or implosion within particular markets and economies, to deflate markets gently or at least tread sideways until more conventional and sustainable settings have time to develop.

Under Yellen, the Fed as a whole didn’t appear particularly concerned about the build-up of risks within financial markets, even if some of its members expressed their unease.

Is Powell a friend or a threat to markets? It may not take that long to find out, with the language that emerges from the Open Market Committee meeting this month — a meeting expected to raise the federal funds rate by another 25 basis points — likely to provide the first insight into whether there are subtle differences between Yellen’s Fed and Powell’s.

Equity markets started this year with surging confidence. They finished last month on a far less certain note.