Nervous banks need to release the handbrake

As rates are held at record lows, nervous banks in the US and Australia are crimping growth by restricting credit.

Rarely in the history of the US, or indeed any developed nation that is growing, have we seen banks so nervous. And those jitters are infectious and have stopped the US recovery from gathering greater momentum.

The bank nervousness extends years before the 2016 election campaign fiasco, although the Clinton-Trump battle has made it worse.

Our version of a similar banking disease has been concealed, firstly by the mining investment boom and secondly by the apartment investment boom and the rise in house prices in Sydney and Melbourne.

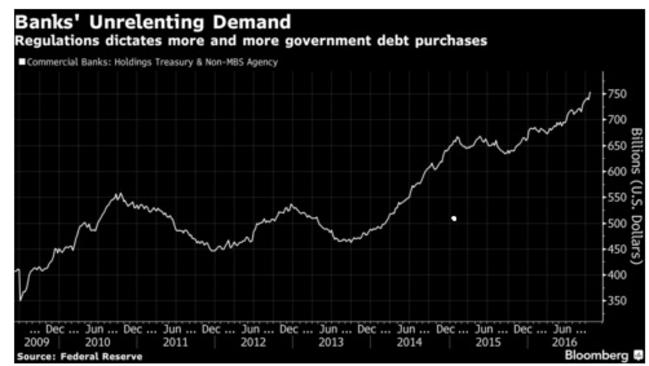

Let’s look at what is happening in the US and I am grateful to Bloomberg for the data.

America’s five biggest bank lenders — Wells Fargo & Co., JPMorgan Chase & Co., Bank of America Corp., Citigroup Inc. and U.S. Bancorp — held a combined $US206 billion of government debt at the end of the second quarter — a 74 per cent increase over the past three years.

The US banks claim that the reason for the big swing to American government securities is that despite token interest rates, bank deposits are rising much faster than loans — i.e. it’s the public that is nervous.

In the third quarter of 2016, the big banks experienced a 6.7 per cent rise in deposits to $US5.2 trillion, exceeding loan growth by a full percentage point.

US government bonds are providing banks with an increasingly attractive spread over what they pay depositors. Two-year Treasury notes yield 0.85 per cent, while the average deposit rate for interest-bearing cheque accounts is 0.31 per cent.

And to take the market risk out of the bond investment, banks hold a big portion of their bonds to maturity so they can keep those investments on their books at the price they paid. Three years ago that was rare.

So, now we have the ultimate mini-risk money making formula — borrow a trillion dollars or so from your customers and lend it to the government shorter term and make half a per cent. That’s better than taking a risk on business loans and households and the bank executives can be sure of a bonus.

Not surprisingly, Bloomberg reports that over the past year, the rate of Bank of America’s commercial-loan growth has fallen from more than 10 per cent to less than 5 per cent. At the same time, consumer lending remains stagnant, contracting for a 23rd consecutive quarter. Citigroup’s retail loan business has also shrunk, while JPMorgan and Wells Fargo, two of the strongest banking franchises in the US, have seen gains in their overall lending slow in recent quarters as well.

Part of the reason for the slow growth is that the regulators require more capital and want safe loans. And that bank caution makes businesses more cautious. It’s actually a form of credit squeeze — a device usually used when lending growth is getting out of hand not when there is restraint and the Federal Reserve is trying to stimulate the economy with low rates.

The whole bizarre situation has not stopped American growth but it explains why such ultra-low interest rates have not stimulated growth in the way they would have in past decades.

Here in Australia, our banks went on an overseas borrowing binge and hosed money at people wanting to buy or develop dwellings — particularly in Melbourne and Sydney. That money has been withdrawn from apartments and developers so there is a rush for independent dwellings and top of the range apartments sending prices higher.

And, in Sydney, the bank apartment nervousness has been offset by finance from the biggest player in the market — Harry Triguboff’s Meriton.

Small- and medium-sized businesses that can’t offer a residence as a security find it tough to get a loan because the banks often don’t have the talent base to assess the value of the business. And, increasingly, entrepreneurs are becoming reluctant to risk the residential house.

We are proceeding down a credit restriction path that is similar to America.

It’s staggering what has happened to the once aggressive and confident US banking system: American banks now own $US2.4 trillion worth of government bonds, including federally guaranteed mortgage-backed securities. And at home we have planted bad seeds that could germinate the same way.