Worthwhile exercise in discipline for big bank bosses

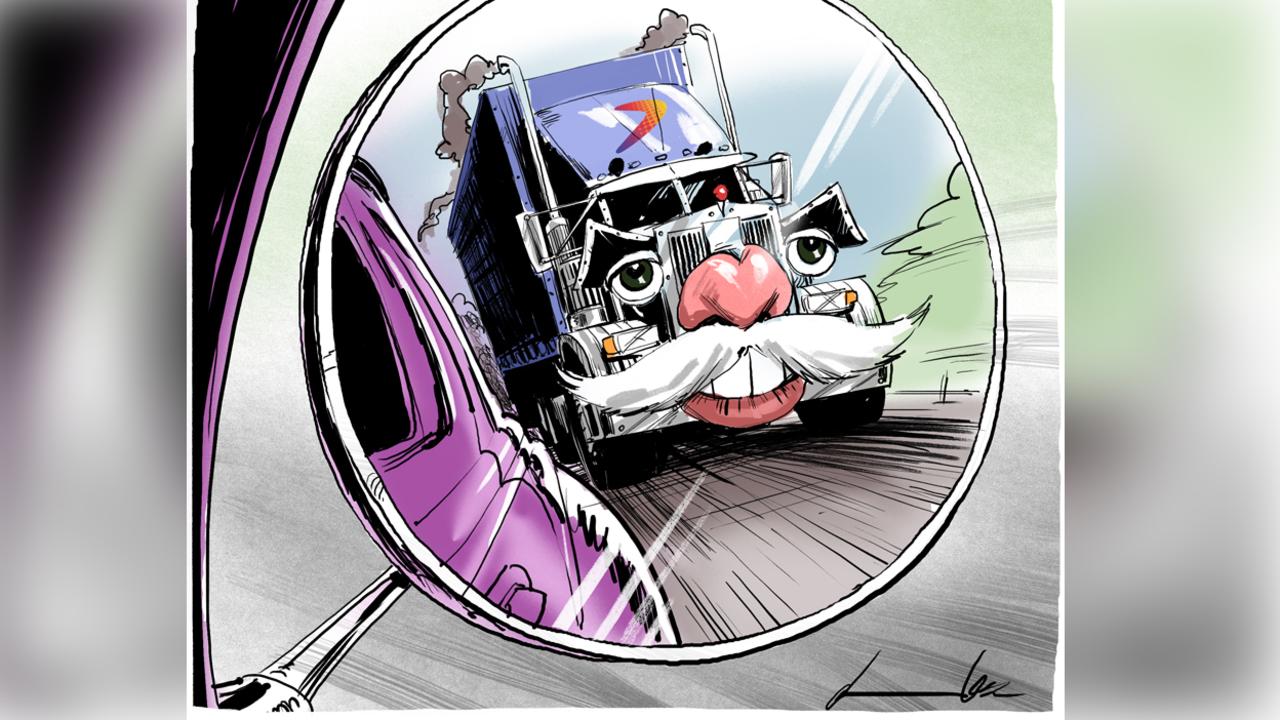

Based on yesterday’s performance, the case for a royal commission into the banks is effectively dead.

Based on yesterday’s performance, the case for a royal commission into the banks is effectively dead: the questions were predictable and none went close to laying a glove on the $12.3 million man, Commonwealth Bank’s Ian Narev.

That said, the mere concept of having the big bank bosses appear before the committee to explain their decisions imposes a discipline that is worthwhile, even if Narev and his sidekick, David Cohen, handled the questions with aplomb.

Committee chair David Coleman put his finger on two of the key competition issues that need to be addressed: bank account portability, and ensuring customers retain power over all bank data relating to them — including taking this with them when changing banks.

The second issue being addressed by the Productivity Commission report into big data is perhaps better expressed as the right to positive credit reports, which means if you have paid your bank debt, then that should be known and to your advantage.

Cohen was quick to welcome another of Coleman’s suggestions: an easing of rules on bank minimum capital levels and the 15 per cent shareholder limit — both seen as impediments to new financial houses starting.

The big banks don’t worry so much about fintech because at the end of the day it will end up making them more efficient rather than vulnerable to competition.

The litany of questions about CBA snafus in wealth management and insurance was largely historic and appropriately handled by Narev and Cohen, with the only further explanation needed being a Dorothy Dixer around risk management reporting.

Narev declined to comment on returns on his home loan book, for competition reasons, but most analysts will tell you the bank earns about 30 per cent on its new loans and 40 per cent on its back book, as home loans are leveraged by some 40 times.

It is a very profitable part of the business, as shown by CBA’s overall return on equity of 16.5 per cent.

The government has handled bank policy badly by dribbling out changes that simply fuel opposition claims of a system in crisis, when in reality it isn’t even close.

The latest are the criminal provisions for index rigging, which at least put Australia on a level playing field with Britain and other regimes, which helps with mutual recognition.

A new banking oversight tribunal to handle complaints is a certainty, and the changes to data rules and bank account details are also a step in the right direction.

But actual decisions are needed rather than further inquiries, when there are already enough, from Murray to Ramsay to Carnell to the Productivity Commission — which will look at bank competition as well as superannuation next year — and yet more parliamentary scrutiny. Banking needs more competition, the government needs to make decisions in a co-ordinated fashion and consumers need more banking services, not more banks.

Harker bows out

Investment banking veteran Richard Wagner will be the new country head for Morgan Stanley on the retirement of long-time leader Steven Harker.

Harker has run Morgan Stanley Australia for a record 18 years, during which he has built the firm from the ground up, starting with 24 staff and increasing that to 600 at present. The firm is now a top three player in the Australian equities market (see table) with comparable positions in equity capital markets and corporate advisory.

In an interview, Harker said the key to the investment bank’s success was “client service through hiring quality people to a firm which is a global leader with extraordinary brand strength”.

Harker, a former official with the Federated Ironworkers Union, joined the firm in 1998 after running the BZW operations in Britain. Before that he was with Meares & Phillips, which became BZW in Australia.

He has built an investment banking powerhouse essentially without the mergers that vaulted other firms, excluding Macquarie, into top positions but with the help of a pre-eminent global franchise.

Citigroup combined with County, UBS with DBSM and Goldman with the House of Were.

Harker will remain as a vice-chair with the firm.

Optus backs Telstra

Potential ACCC regulation of the mobile phone industry has achieved rare agreement between Optus and Telstra, with the former strongly backing the latter’s opposition to any policy shift.

Only Vodafone is backing the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission.

In a speech at yesterday’s CommsDay conference in Melbourne, Telstra regulatory boss Tony Warren launched a broadside at Vodafone accusing it of being at best duplicitous. The reason being that all around the world, except in regulated markets, Vodafone is opposed to mobile regulation but, incongruously, in Australia it is backing moves by the ACCC to possibly declare a wholesale domestic mobile roaming service.

The issue is domestic roaming, that is, if you have a Vodafone phone and travel to a part of the country where its network is poor, you can switch into, say, a Telstra network.

Vodafone would have to pay for the service, and the ACCC is looking at monitoring the price charged.

In all the big towns there is competition, but farmers complain once you drive 150km from Dubbo, reception is down to Telstra, so there is no competition.

Telstra argues it built the network and this was its competitive advantage, which the others could follow but the last thing you need is more regulation.

The regulator has been careful not to say just where it is heading, which is another issue as it has just launched a major market study into the sector.

ACCC boss Rod Sims told the CommsDay summit he would have an issues paper out on the roaming review by the end of the month, noting the idea of having a separate review was to get the answer out early.

A draft decision will be out early in the new year, with a final decision a couple of months later.

The market study draft will not be released until the middle of next year.

Warren made the point that competition was strong in an unregulated market and investment by the major operators underlined this point. Telstra was spending $1.7 billion a year on its mobile network, Optus about $950 million and Vodafone about $600m.

Mobile phone services operate on a national market, so more competition in the city leads to better service in the bush, and if you pay $1 a minute in Melbourne you would pay the same in the middle of the country.

But if the ACCC declared the service, then it would have to work out the price to be charged in the middle of the country, which would almost certainly be higher than in the bush.