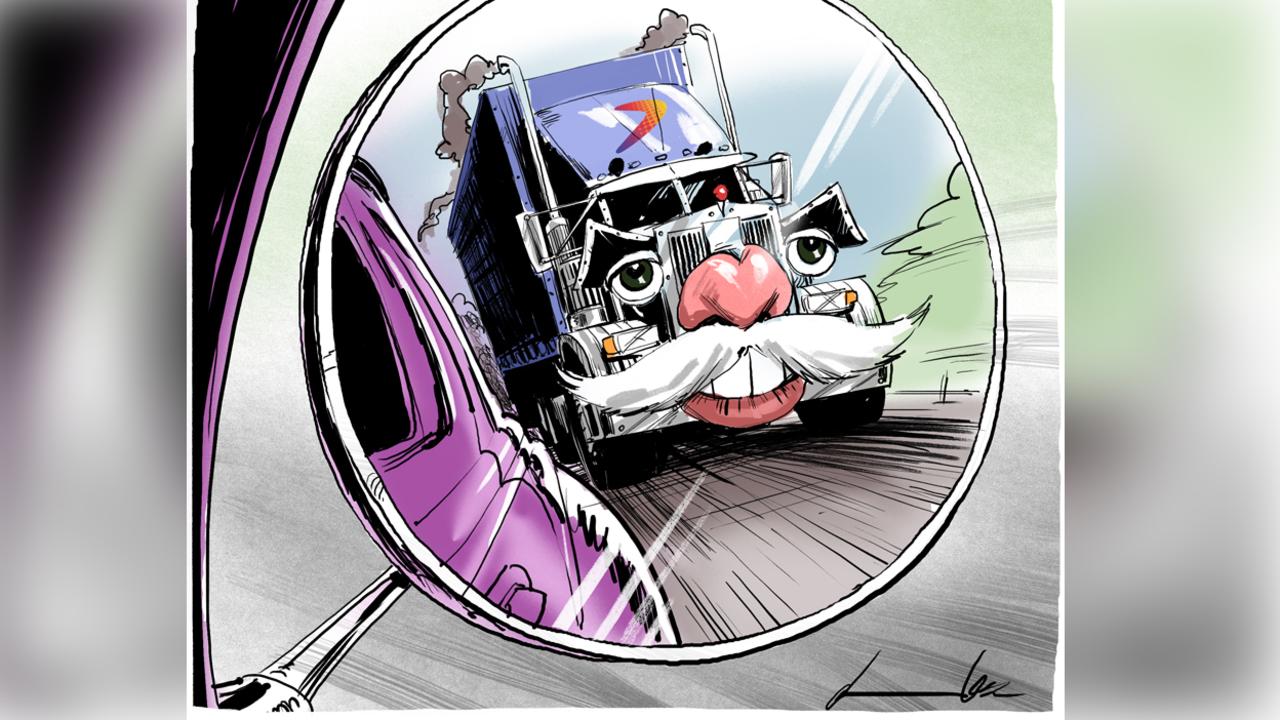

Interest rate cuts help banks put profits ahead of customers

Yesterday’s rate cut was a nonsense when it comes to providing any meaningful boost to the Australian economy.

The fear is the RBA has joined its international peers in misguided attempts to manage currencies, but if the aim was to boost demand, investment or prices then it was a complete waste of time.

Hopefully, Friday’s statement of monetary policy will provide more reasonable explanation of just what was in Glenn Stevens and his board’s collective misguided mind yesterday.

If the RBA was wasting its time, the big banks were in a state of active profit management, with the big bank oligopoly once again thumbing its nose at the political pressure it is supposed to be under.

The RBA move was designed to push the Aussie dollar lower, but in doing so, as economist Saul Eslake has noted, it effectively gave up some firepower should such a move become really necessary — by way of example, the likely collapse in the US dollar if Donald Trump wins the presidential election.

Inflation growth or employment are no better or worse than last time the RBA cut in May, so you have to wonder just what really forced the bank’s hand yesterday.

If, as suspected, it was currency management then that is an exercise in futility, despite the short-term fall yesterday.

The RBA has already cut inflation estimates from 2.5 to 1.5 per cent for this year and from 2.5 to 2 per cent for next year, and yesterday’s move will have little impact.

At a time when a hostile Senate makes some sort of bank inquiry a certainty, the big banks are batting on, seemingly oblivious to the political noise and managing their businesses for shareholders above all.

While the banks cut home loan rates by less than half the RBA cut and raised term deposit rates by more than double, rates on credit debt — which stands as high as 18 per cent — remain unchanged.

This is one area of focus by the opposition, which is demanding a royal commission into the banking industry.

The government is already committed to a Productivity Commission inquiry late next year into financial services competition, as recommended by the Murray Committee, but while supporting the move, it is yet to formally initiate the study.

The PC review is one more reason there is no need for a banking inquiry, but Treasurer Scott Morrison is strangely mute on the subject.

CBA chief Ian Narev will spin the numbers next week, giving a bit to each of his stakeholders as he unveils a profit of about $9.6 billion, against $9.1bn in the 2015 financial year.

Bank return on equity is falling, with UBS analyst John Mott forecasting returns on equity to fall to 17.1 per cent last year, down from 18.3 per cent in 2013, and en route to 14.1 per cent in 2020.

The average return on equity for a top 200 company is closer to 13 per cent, underlining the profitability of the big bank oligopoly.

The increase in deposit rates yesterday is designed to lock in funding, but will be sold by the banks as evidence they are looking after pensioners and others who rely on bank deposit rates for their income.

Cuts in home loan rates have to be passed on to the entire historic loan book, while deposit rates only apply to new money.

CBA was out in an instant yesterday, cutting home loan rates by just 13 basis points and NAB followed soon after, cutting its rate by just 10 basis points, less than half the 25-basis-point move by the RBA.

In the past banks have waited a few days before making their rate moves.

Both banks increased deposit rates by more, with CBA raising term deposit rates by 55 basis points in an attempt to maintain funding sources.

At 3 per cent, CBA 12-month term deposit rates are now double official cash rates of 1.5 per cent.

Both moves put pressure on bank profit margins, but the home loan cuts hit hardest because they apply to their entire loan books.

CBA term-deposit rates are now back to the same levels as a year ago while the 5.22 per cent standard home loan rate is the lowest on record for the bank.

By deciding not to pass on the full amount of the RBA cut the banks are obviously protecting profits and shareholders at the expense of customers.

The CBA has net interest margin of 2.1 per cent, which rates in the top tier of its global peers.

Mystery writedown

UGL recovered from earlier falls but still finished down over 4 per cent yesterday at $2.37 on confirmation it will take a $200 million writedown at its coming results announcement.

This followed a writedown from LNG joint venture partner CH2M Hill in the US of $US95m, which while for just one of the company’s two projects is in line with June warnings from UGL about a large writedown.

Just why it can’t detail the news now is not clear, but it has previously disclosed the potential damage, which hit its stock price hard, falling from a near-term peak in early June of $3.67 a share.

Outside the Qube

Aurizon’s formal split from Qube at their Moorebank intermodal facility in Sydney yesterday is the logical conclusion of its deal back in May to lease a rival terminal at Enfield from NSW Ports.

The split also suits Qube’s Maurice James, because it means he will now own 100 per cent of the Moorebank freight hub after paying book value of $98.9m for the 33 per cent owned by counterpart Lance Hockridge at Aurizon.

All is now set for Qube to put its foot on the accelerator to develop the long-term Moorebank project site, with Patrick to return to the company on August 18 when Qube and Brookfield’s $2.9bn acquisition of Asciano’s Patrick container terminals is formally completed.

The joint-venture partners will pay $957.5m each for the deal and borrow an extra $1bn for the business, which will be run by Qube’s Michael Jovicic.

Aurizon’s Enfield deal with NSW Ports satisfied its objective of trying to establish a bigger intermodal operation in NSW.

Yesterday’s sale of its freight hub stake also means Aurizon won’t have to pay $230m due to help fund the Moorebank build.

Rail accounts for about 15 per cent of the output from Sydney’s port and the NSW government is keen to at least double its share to 30 per cent, which suits Aurizon and Qube, and the latter will be effectively competing for business.

Qube wants to get as much traffic as possible through its Moorebank facility and will run an open access train platform so Aurizon can still gain access should it see the need.

Walking away from the Moorebank expansion is another sign of Aurizon returning to its core business after quitting a proposed $1bn-plus West Pilbara port expansion project. Aurizon’s stock price fell 1.2 per cent at $5.14 and Qube was up 0.8 per cent at $2.60.

Yesterday’s rate cut was a nonsense when it comes to providing any meaningful boost to the Australian economy, and this was evident by the noticeable lack of any substantive reasons for the move in the RBA’s statement.