For markets, good news from US Fed seems bad

A Fed rate rise would show some confidence in the US economy, even if it means an adjustment for the markets.

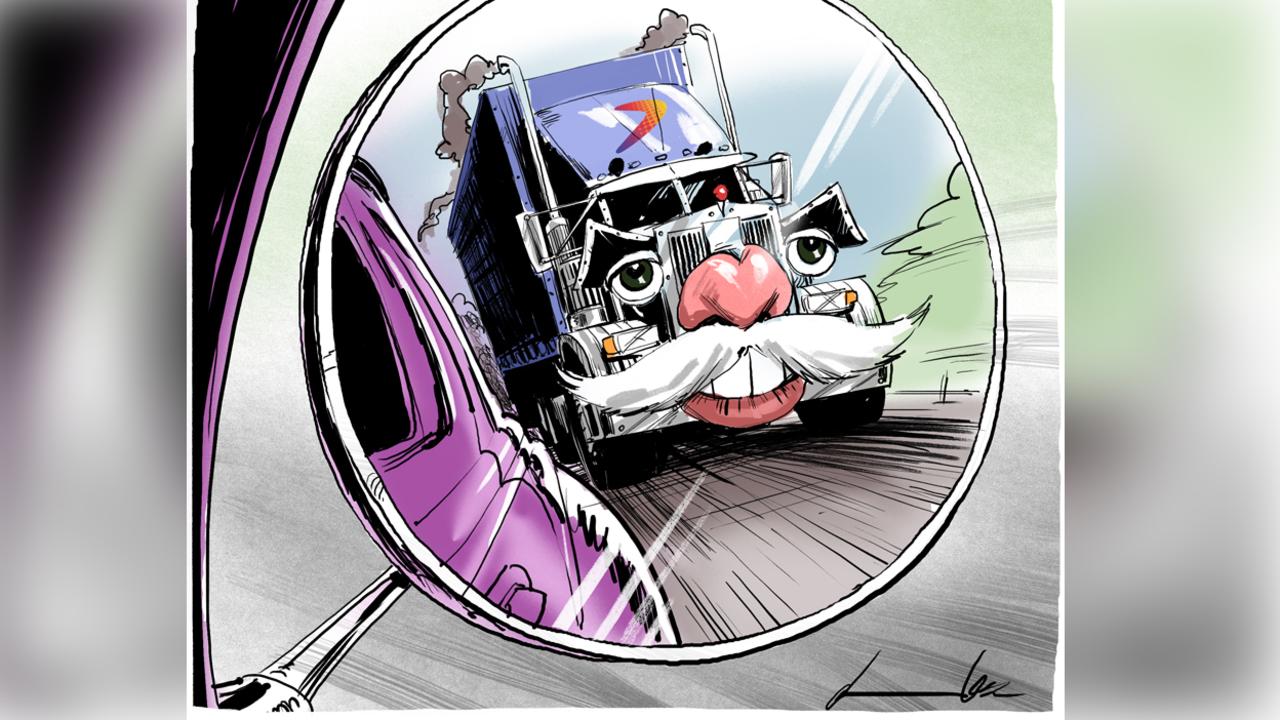

The stockmarket has traded on the line that bad news is good news for much of the past seven years, so much so that the yield trade was overcrowded and overdue for a correction.

Defensive stocks that pay big dividends, such as real estate companies, Telstra and infrastructure stocks, have led the market, but in recent weeks there were signs the story had had its day.

One month ago, industrial company stocks were trading at over 19 times forecast earnings, which was the highest level since just before the GFC and at levels only seen once before, being before the 2001 dotcom crash.

The stockmarket was showing signs of being overvalued and certainly a lacklustre corporate earnings season gave little room for hope of a big rebound in profits.

Just how severe the volatility is will be seen in the near term, starting with last night’s (Australian time) speech in Chicago by Federal Reserve governor Lael Brainard.

With the market at a crossroads, there were two theories advanced yesterday for the sell-off: that markets were spooked by the prospect of an interest rate hike, and the other that they finally realised that monetary policy globally had reached its limits.

The first reason is more bullish because after some short-term pain the only reason why the US Fed would be lifting rates is because it is satisfied the economy is back on a growth path. That is unequivocally good news.

For the market, it means a short-term adjustment. After all these years of bad news being good, because it has meant lower interest rates, now the good news, that the economy is good, is bad news because this means higher interest rates. On any view of the world, a short-term adjustment aside, all we are facing is that the markets must get used to a more normal world where stocks and bonds trade to some extent in opposite directions.

Bond yields rise when prices fall, so yesterday as Australian 10-year bond yields rose from 1.9 per cent to 2.1 per cent, prices fell and in Germany yields actually became positive again.

The second scenario is mostly bad news because, frankly, no Western government, including in the US and certainly Australia, has shown itself to be anything approaching functional and capable of guiding their respective economies back to growth.

So if monetary policy is shot, then what’s left?

Credit Suisse’s Hasan Tevfik offers a glimmer of hope on this front when he points out that China is planning a major fiscal boost, which can only be good news for Australia.

In the short term, of course, there is market dislocation as investors get used, hopefully, to a new world order that proves more normal trading.

The Fed’s Brainard is dovish by nature, like Boston Fed president Eric Rosengren, who sent the markets into turmoil last week by saying “a reasonable case can be made for continuing to pursue a gradual normalisation of monetary policy”.

That means an imminent rate rise, with speculation resuming for an increase at next week’s policy meeting.

Two sets of weak numbers last week had the market believing the next Fed move would come in December at the earliest, and this may still be the case.

If Brainard repeats the Rosengren message, then Wall Street will assume a rate hike is a near certainty and stock prices will resume their falls as the yield trade unwinds.

One of the few stocks to rise yesterday was QBE, a global insurer with $US25 billion ($33.3bn) in US bonds, so a 1 per cent increase in US bond yields means an extra $US250 million in pre-tax income.

The yield trade has meant so-called defensive stocks such as real estate trusts and infrastructure stocks have led the market and yesterday Goodman was down 3.9 per cent to $7 a share and Transurban down 2 per cent to $10.64.

The best news for stock prices would be a Fed rate rise, which at just 0.5 per cent is hardly crippling but at least it would show some much-needed confidence in the US economy. After a short period of turbulence, stock prices would resume “normal trading”, but the reverse is much more worrying.

Banking on services

NAB’s Andrew Hagger gets the message that people need banking services, not banks, hence his mantra that NAB will be more than money to you.

It’s a good line, but, as he acknowledges, it is not so easy to be as good with people as the bank is with money when frankly the bank hasn’t been that good with your money all the time.

But the starting point is acknowledging the issue, so a big tick on this point and now comes the tough bit, building trust and confidence, making it easier for customers and supporting customers.

NAB, like its rivals, is hoping technology will help it achieve at least some of its aims, which explains why it is investing in digital.

O’Brien’s payout

Woolworths has not declared the cost of any payout to former boss Grant O’Brien, with the company’s annual report released late last week silent on the issue.

The report noted O’Brien formally finished work at the company on August 1, which meant he had reached the age of 55, entitling him to participate in the company’s defined benefit scheme.

No executive was paid any short-term bonuses last year, although company secretary Richard Dammery received non-monetary benefits totalling $469,967 to bring his final pay to $1.6m.

Woolworths chief executive Brad Banducci was paid $2.3m, reflected in part by the fact he only served in the top job for part of the year and his fixed pay has since gone to $2.5m.

The old defined benefits scheme is rumoured to pay benefits based on five times final fixed salary, which for O’Brien was $2.2m, making the payout about $11m. The company is declining to comment, saying it is a private matter for O’Brien.

The level of his superannuation is, of course, in part determined by any personal contributions, which is a private matter, but company contributions are a matter of shareholders.

This year, by way of example, the company said superannuation benefits cost shareholders $446,000, up from $435,000 the prior year.

It also noted there was a further sum of $444,758 in long service and other benefits paid to O’Brien, effective August 1, which was outside the cut-off date for the annual report and was not included.

Nippon paper deal

The old Paperlinx empire is being recreated, with Nippon Paper-controlled Australian Paper wanting to buy the Edwards Dunlop division owned by Sydney-based BJ Ball.

Australian Paper, which sells under brands including Reflex, is the only Australian company making photocopying paper, and Edwards Dunlop is a rival distributor and importer.

The division was sold by then owner Paperlinx in 2001 to a private equity firm and eventually found its way in Ball’s hands.

The division was sold along with Commonwealth Paper because that was the only way the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission would approve the Spicers deal.

The old Paperlinx is now called Spicers.

The Australian market is wide open to imports, although Nippon maintains a strong hold by supplying the likes of Officeworks with its house brand photocopy paper.

The Nippon deal is subject to ACCC approval.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout