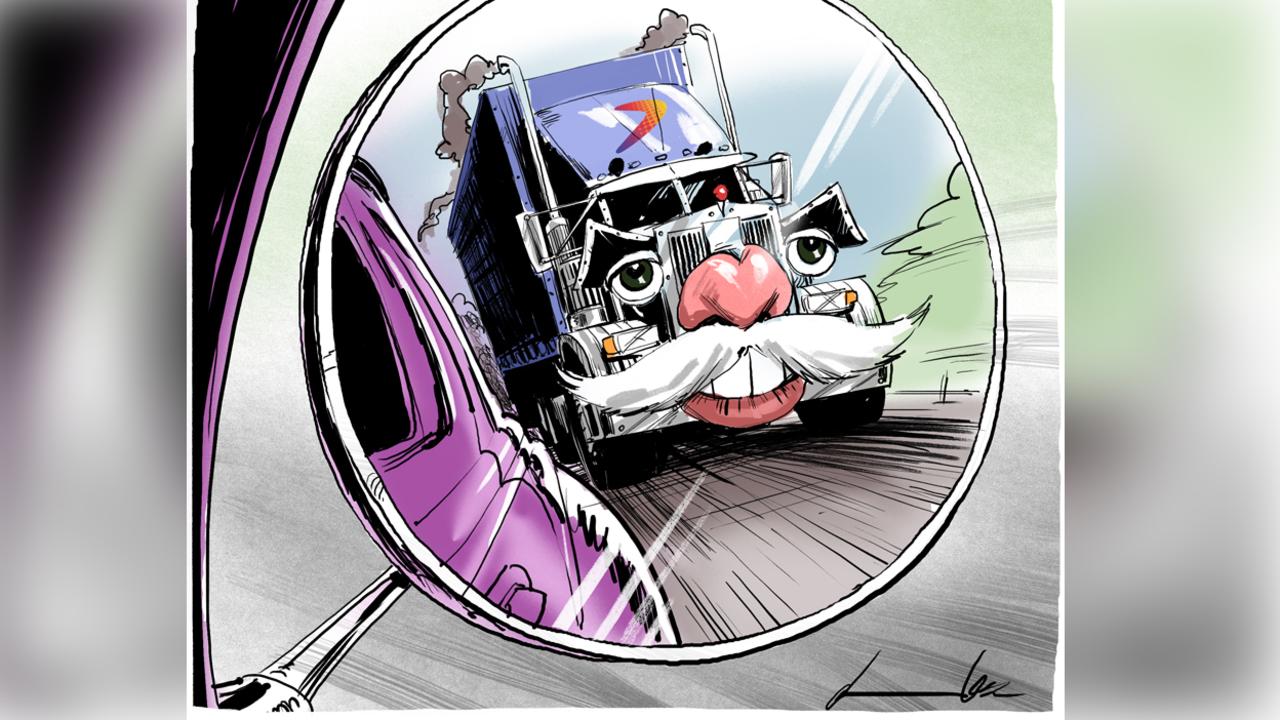

David Murray leads cavalry to AMP rescue

David Murray has taken on the biggest challenge of his career trying to save AMP.

David Murray has taken on the biggest challenge of his career trying to save the badly damaged financial services company AMP from structural changes affecting the financial advice industry and the fallout from the royal commission.

His appointment is a coup for the company and relieves the pressure on acting chief Mike Wilkins, who will now work with Murray and the board in trying to restore the company’s tattered reputation, after it admitted to stealing from clients and lying to the regulator.

Murray’s appointment comes as shareholders are expected to protest against three incumbent directors — Holly Kramer, Vanessa Wallace and Andrew Harmos — at next week’s annual meeting, but all three are likely to be returned with votes against re-election of about 35 per cent.

This will allow Murray the chance to design his own board.

The former CBA chief left the bank 13 years ago and, apart from serving as the Future Fund chairman and the Financial Services Inquiry chief, he has avoided big company boards, saying he would only join the directors’ club if a specific challenge was presented.

There is no bigger challenge in corporate Australia today than saving AMP, which is suffering from a reputational savaging and coming radical changes in the structure of the financial advice sector.

Operational issues aside, Murray’s job includes establishing a new corporate governance framework at board level to chart the company’s long-term future.

AMP now has a highly respected and knowledgeable chairman and chief executive to restore the company before Murray finally retires to his newly acquired cattle farm in the NSW Hunter Valley.

Auditor’s privilege

KPMG Australia chairwoman Alison Kitchen soon learned that if she wanted to get somewhere in competition with a male colleague she needed to be better and work harder, and as events happened she was and she did.

Kitchen said “women were just assumed to be not as good”.

After settling on a career in chartered accounting starting in Liverpool, England, she was one of five graduates to pass her professional year exams.

She had passed through interview rounds and been told she had “nice legs” and was “attractive and pleasant to talk to”.

Her parents had instilled in her a Protestant work ethic, which helped after rejecting the career as a physiotherapist, which her mother had always assumed she would follow.

There was the issue of the green crimplene trousers she would have had to wear but in truth business attracted her and by the time she landed in Perth in the late 1980s she thought she was in heaven.

She came to Australia for what she thought was a limited time following her doctor husband on a work placement.

This was a heady time in the wild west: Alan Bond and Laurie Connell were at their peak, Fremantle was the home of the America’s Cup defence and small mining companies were being created by the day.

As an auditor this was an extraordinary era, “everything was done on the smell of an oily rag and because the companies were small we were expected to do everything around the place”.

Kitchen says the work was nothing short of “exciting”.

Late in the decade, of course, the sharemarket crash changed the game and Kitchen got to know some of the firm’s stars, like then insolvency guru David Crawford.

It was also when she got a big break with a call from Doug Dukes wanting her to be a female partner at the firm. He was looking for someone with mining expertise, and who better?

Kitchen was trained as and remained an auditor, which she said “means you need an inquiring mind. You have to be curious, get on with all sorts of different people so they will talk with you and have the ability to look from a helicopter sights rights down to the detail.”

She was also not afraid to take on different jobs, starting in Britain as an auditor for the National Union of Mineworkers.

One afternoon she was left in the office alone with legendary union boss Arthur Scargill, who took her through his political philosophy. His passion was impressive, particularly as this was when Margaret Thatcher was at her peak and “the miners had absolutely no cards with which to play”.

“When you have nothing you learn the importance of fighting the good fight,” she said.

When she joined the national partnership board, Kitchen worked closely with marketing boss Helen Cook, who gave her a lesson in politics and psychology.

“She was inspirational for me and taught me the power of different thinking,” Kitchen said. “You have to step out of your comfort zone if you are going to get ahead.”

Together with Cook, she would road-test strategies and tactics.

At 41, on the national board at KPMG, the northern England born-and-bred auditor was in a different league. But the experience also taught her the benefits of diversity. “People have different ways of doing things and different ways of thinking.”

The promotion meant a move east to Melbourne and also a change in style, moving to the plum BHP audit. Along the way she learned the benefit of moving out of her comfort zone. “I listened a lot, picked my fights, don’t pick a fight you can’t win, sweated the small stuff and learned not to run into a brick wall,’’ she said.

But Kitchen confides, “it’s a privilege to be an auditor”.

Investors cheer Moore

This month marks the 32nd year Nicholas Moore has worked at Macquarie and his 10th as boss. His firm has been successful through its commitment to risk management.

Moore has taken the APRA committee report on CBA to his board and management committee with a benchmarks study looking at what it did and what Macquarie does.

It is an exercise other companies are running but the point Moore and his chairman Peter Warne want to ram home is that for a firm that spends $400 million a year on compliance this is a constant ongoing practice, from its annual human capital report down.

Macquarie has 54 per cent of its staff outside Australia and earns 67 per cent of its money offshore, even if Australia is the largest single source of money.

Moore took the reins in 2008, when some doubted whether Macquarie would survive, and since then returns on equity have increased from 9.9 per cent to 16.8 per cent, and profit has increased from $871m to $2.6 billion. Total shareholder returns have gone from negative 44 per cent to 44.6 per cent in the 2017 year to 20.1 per cent this year.

Moore owns 2.3 million Macquarie shares and earned $12m in dividends, and his heir apparent Shemara Wikramanayake earned $3.7m on her 710.003 shares.

Moore’s share of the Macquarie profit pool was $18.1m and in the middle of the bleak period for Australian banks was happy to report statutory salary of $19.7m and shareholders are cheering.

This year looks a little bleaker as far as performance fees are concerned, but the bank — which has the equivalent of some 25 per cent of Australian energy needs under management from a Philippines geothermal plant to wind power around the globe — manages to find new sources of income.

That explains why with global growth powering ahead from a subdued Australian economy, Macquarie’s stock price closed up 0.5 per cent to a near record high of $108.22.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout