Banks start fighting back

CBA boss Ian Narev was praised this week for his feisty defence of his company amid a backlash against big business.

He would be the first to acknowledge that some business leaders are good at dealing with stakeholders, including staff, but few can connect with those leading the anti-business campaign.

The same applies to BCA boss Jennifer Westacott. She is a policy master, which goes well with senior bureaucrats but not so well at the local pub.

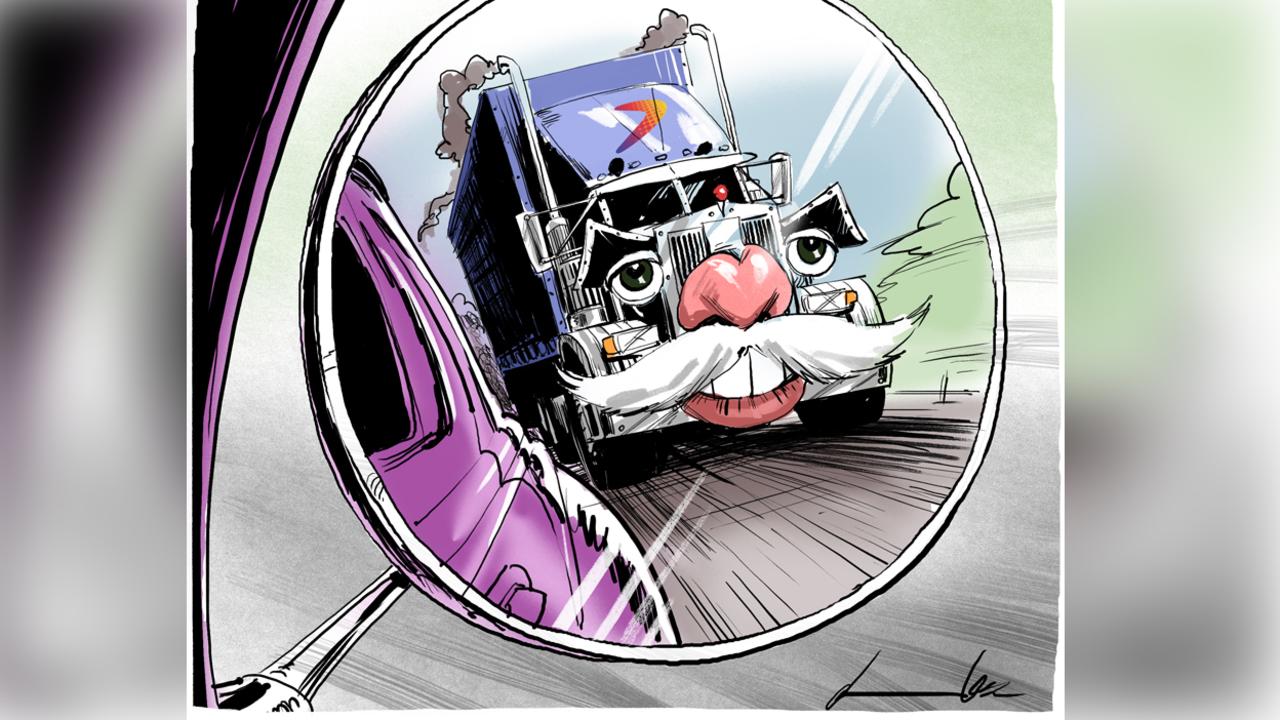

The dilemma for business is how to get its message through to the punters when the dangers of losing its social licence are being rammed home by politicians.

The reality is, whether they like or not, business leaders need to change tack and start selling a message few of them are comfortable selling. Many are unimpressed at this intrusion into their normal duties and, behind closed doors, some are getting more than a little testy about it.

Failure will lead to inevitable reactions such as heightened parliamentary scrutiny. For example, British Prime Minister Therese May is flagging myriad reforms, including worker representation on company boards.

The average pay of the top 11 bosses in Australia is $5.5 million, which works out at around 68 times the average pay of $80,000. This is considerably better than the 140 times average pay that British bosses earn and the 204 times that US bosses earn.

May wants British companies to publish the multiple in their annual reports as part of a campaign to close the gap, including going a step further than in Australia with binding remuneration votes.

Pay is an obvious point of contention but wider issues are increasingly becoming a focus of attention for big business.

AGL’s Andy Vesey says business should not be diverted but notes “the way we manage the business is by doing good things”. His idea is business should simply show it is doing the right thing.

Increasingly, companies are including key statistics in their results package, showing how they affect society. CBA, which employs 41,400 people, pays $3.6 billion in tax — enough to fund 240 schools and six hospitals and nearly double the annual budget of the Australian Federal Police and Department of Environment. Wesfarmers employs 220,000 people, pays $8bn in salaries, $40bn a year to suppliers and $1.3bn in tax.

ANZ boss Shayne Elliott admits: “We need to do more to explain how the bank works and the reasons for the decisions we make. That is going to require being more transparent with factual information like funding costs.

“We need to build a better understanding of the role of banks in creating a balanced, sustainable economy in which everyone can take part and build a better life. Strong banks also protect people’s savings. They support people’s retirement through returns on their superannuation. And strong banks mean no call on the government and the taxpayer for support when things are tough.”

Banks are caught in the headlights partly because they handle our money; they are some of the biggest companies in Australia and the big four oligopoly can be extraordinarily arrogant.

Why did none of the big four figure it might necessary to explain their miserly rate cut moves to the public, particularly at a time when their British comrades were passing on rate cuts and after going through an election where bank royal commissions were the flavour of the month.

As the accompanying item shows, the banks may be balancing different stakeholder needs when their primary goal is to boost profit margins in a tough business climate. That’s fine so long as it comes with some explanation.

Floating feeling

The first half was relatively active for new floats, with ASX figures showing 47 new listings raising $24bn. Investment banks are gearing up for the traditional third-quarter rush with eight to 12 new floats raising about $5bn.

The names already mentioned include Kiwi fisheries group King Salmon, the $1.5bn sale by TPG of Inghams chicken, Good Guys, Moly Cop, Charter Hall’s WALE (weighted average lease expiry) sale and the mooted sale of Alinta by TPG. The selling point will be growth, with these privately owned companies raising money to fund expansions, in contrast to last year’s balance sheet repairs.

Capital capers

Commonwealth Bank has increased its capital levels 4.7 times from $9bn in 2007 to $42bn, underlining how regulatory demands have increased costs. But the increase is not as big as it looks. At the same time its assets increased from $370bn to $950bn, or 2.6 times, so the bank was going to need more capital anyway.

Regulators have changed the rules, including requiring advanced accreditation banks to have a 25 per cent risk weighting. This still gives the big four banks an edge over the so-called standard accreditation banks such as Bendigo, which have a 40 per cent weighting.

This means Bendigo has to keep $36,000 in capital for every $1 million in home loans, whereas ANZ Bank, for example, has to keep just $22,000, highlighting the difference between an advanced accreditation bank and a standard bank such as Bendigo. The difference was larger before.

Bendigo and Suncorp, among others, are closer to getting advanced accreditation, which will help increase competition.

In a recent report, UBS’s John Mott highlights just why CBA only passed on some of the 25 basis point cut in mortgage rates.

In the latest half, mortgage brokers accounted for 49 per cent of all new mortgages at CBA, which has not seen any increase in house sales for the past three-and-a-half years. The total market share of so-called proprietary mortgage sales has fallen from 33 per cent to 26 per cent over this period, with sales around the $23.7bn mark.

Broker sales often mean discounts have to be offered, which means lower profits, and in the last year CBA’s retail mortgage margin has fallen by seven basis points to 126 basis points.

The margin for a residual of loans in the back book is higher at 136 basis points because discounts are not given or claimed.

If CBA has to keep discounting at the front end of its book then it needs to make up some ground at the back end.

And that is precisely what happened last week when it didn’t pass on the full impact of the Reserve Bank rate cut. It’s getting tougher to make money in banking as interest rates fall.

Yearning for earnings

The market was disappointed in the numbers from CBA and Telstra at the big end of the market, with both losing value as a result.

But today’s table reveals little in the way of changes to earnings forecasts for the present financial year with slight upgrades coming ahead of next week’s results deluge. Last financial year’s earnings per share were said to be down 7.7 per cent and this year this is expected to bounce to a 9.7 per cent gain. Fourth-quarter weakness was noticeable in this week’s releases.

Commonwealth Bank boss Ian Narev was praised this week for his feisty defence of his company amid a global backlash against big business and elites of all shapes and sizes.