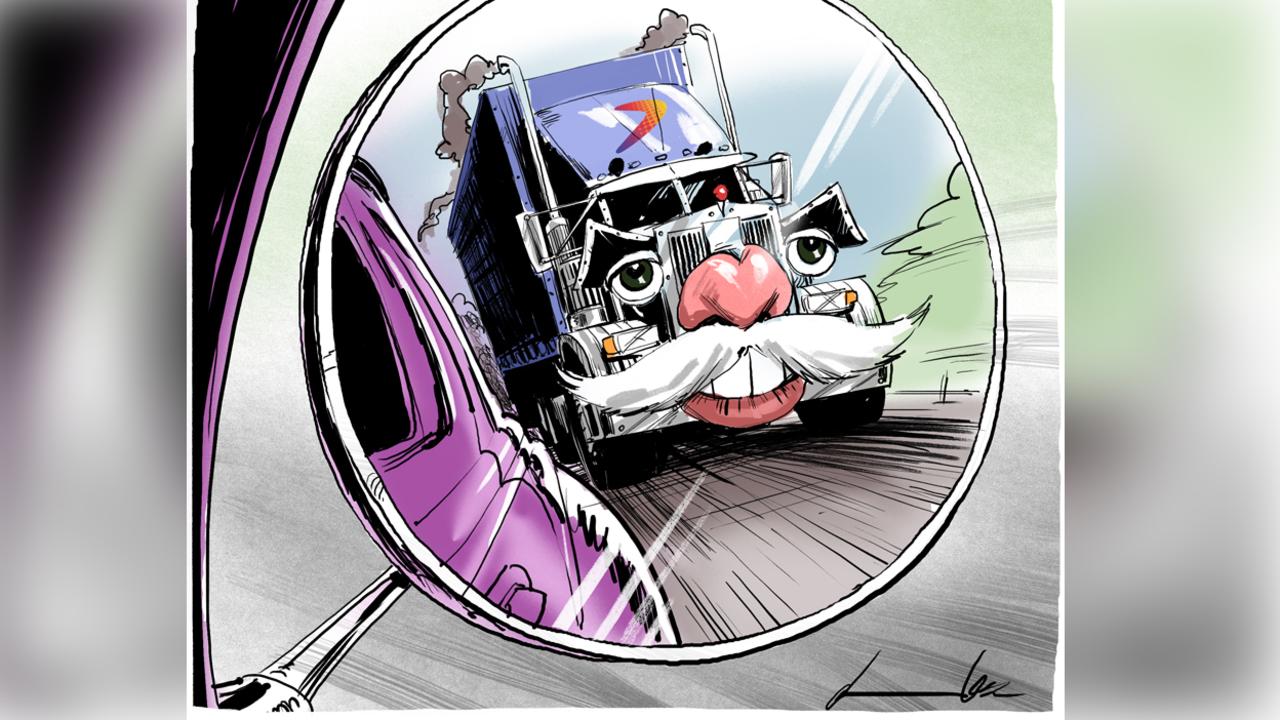

Arrium collapse: errors were heaped on error

The almost operatic collapse of Arrium provides a textbook example of what can go wrong at a company.

The almost operatic collapse of Arrium provides a textbook example of what can go wrong at a company, and one where most of the blame would fall within the ballpark of former chairman Peter Smedley’s team.

Smedley was chairman for 14 years from the day BHP spun out its unwanted steel division in 2000 with a huge $1 billion debt load.

It is easy to pick out mistakes in a failed company after the event but not so simple in the middle of trying to run the company amid volatile exchange rates and, in more recent times, a 60 per cent fall in steel prices and a collapse in iron ore prices from $US190 a tonne in 2011 to $US55 now.

There are, however, decisions that in retrospect could have averted this mess.

At the outset, it should be said the doom pervading Whyalla may yet be diverted — it all depends on what decisions are now made by Paul Billingham and his team at Grant Thornton.

Voluntary administration is designed as a more efficient way of dealing with a failed company.

In part this is because decisions are ultimately taken by the administrator, who must be sure he or she gets the best price for the asset.

The administrator has a few options: to return the company’s top directors (rare); liquidation; and deed of company arrangement, which is a deal with creditors. The administrator effectively replaces the board but importantly acts on behalf of all creditors, not shareholders.

The reason why the company tried to avoid voluntary administration is the contagion effect it will have in South Australia where all the small companies who deal with Arrium now effectively have to write off their asset pending any better conclusion.

The banks, which were so keen on the appointment of a voluntary administrator, knew it was an unacceptable conflict to have their adviser, McGrathNicol, in the role.

But by rejecting this option, the company denied itself the chance of getting $400 million in cash in a bank-friendly deal.

This money will now have to be found elsewhere, which is not impossible, but whether the banks emerge better than losing 45c in the dollar is still uncertain.

The company’s Blackstone deal, which angered them so much, would have reduced the value of their loans by 45c in the dollar.

The government is working to revamp the voluntary administration process by giving boards more safe harbour protection for directors against insolvent trading bans and to ensure voluntary administration doesn’t automatically trigger the collapse of all contracts with the failed company.

The idea is to provide more flexibility to give companies a greater chance of survival.

BHP Billiton erred on day one by loading Arrium with too much debt when it floated, and Smedley’s crew compounded the error by expanding in cyclical industries funded by debt.

That is error one.

Then when things started to get tough the company forgot the first rule of business — to keep its bankers informed about what it was planning to do.

The banks may have been tough by taking out $800m in facilities last year, but this was no excuse for the company talking out $300m days before doing the Blackstone deal, which the banks read about on the ASX screens.

In 2012, the company received a 75c-a-share takeover bid from Korean steel giant Posco, which was subsequently raised to 88c a share but rejected. This now looks like a dream deal.

Then, two years ago, it raised $754m at 48c a share, which merely underlined the mess the company was in.

This was Smedley’s final act before handing over the reins to Jerry Maycock in late 2014.

In all, it was a sorry saga, which Grant Thornton will have to sort through amid some extraordinary political nonsense.

To suggest the company’s failure is anything more than failed business strategy compounded by cyclical markets is a nonsense and that is where the argument starts and finishes.

Sutton charges ahead

Two profit downgrades later and Bank of Queensland’s Jon Sutton on Thursday did what many company bosses dream of doing and raised his prices to offset falling margins.

The increase in home loan rates could set a precedent in Australia, with a regional bank leading the charge to hit customers.

Normally it’s the big guys who lead the charge, as Commonwealth Bank et al did early last year by not passing on the full 25-basis-point April interest rate cut to 2 per cent.

BoQ lifted its standard variable rate by 12 basis points to 5.86 per cent.

Politically only a small bank could have got away with such a move the day after the Prime Minister gave the industry a serve about looking after customers.

Just what caused BoQ margins to fall depends on who you talk to.

Some analysts suggest Sutton was caught with an overloaded mortgage book, in which sales increased 1.6 times system due to rapid increases in broker-led loans.

The bank says that’s not the case at all — rather its costs rose about 30 basis points due to the turmoil on global financial markets earlier this year.

As an aside, Sutton is in 150 per cent agreement with Malcolm Turnbull on the issue of ethics.

His chief risk officer, Peter Deans, heads a special ethics committee at the bank and over the past six months has worked with the St James Ethics Centre in running ethics lessons for staff.

“Perception is everything,” Sutton confided in a chat with this column.

“Banking comes with a social licence,” he added.

Having an ethical culture doesn’t mean snafus won’t happen or rules won’t be broken.

But it’s how you deal with the them that is the mark of an ethical organisation.

Sutton has run BoQ since leaving Bankwest four years ago, and he is working overtime with some success to diversify its base away from Queensland. About 62 per cent of all new loans now come from outside the state.

When the Virgin Money transfer takes place next month, it will only increase the bank’s national reach.

Sutton is generally satisfied with the state of the national economy, saying it is making a “good” transition from mining dominance. Queensland remains patchy but NSW is strong.

Having taken the decision to tap customers with higher rates, the market will be hoping the steady stream of profit downgrades now stops.

The bank’s share price fell 1.2 per cent to $11.45 on what most analysts say was a weaker than expected half-year profit of $186m.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout