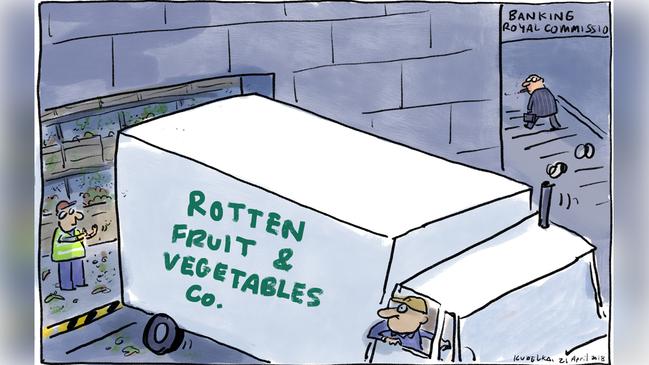

AMP chairwoman Catherine Brenner must go now

AMP chairwoman Catherine Brenner was caught red-handed in the middle of the cover-up.

Had AMP acted in May last year when it first referred its theft from clients to the Australian Securities & Investments Commission, chairwoman Catherine Brenner might have had some credibility. However, yesterday’s moves are frankly little better than a joke.

The chairwoman was caught red-handed in the middle of the cover-up. Brenner must realise cultural change starts at the top and that means she must go now.

If she doesn’t, then she needs to be told.

The financial services industry has had arguably its worst reputational week in history. The message has surely sunk in about the need for an overhaul of an arrogant corporate culture in a cosy oligopoly that has thrived rewarding executives and shareholders at the expense of customers.

It is a short-term corporate strategy doomed to failure and that is what it is facing today.

AMP is lucky to have someone of Mike Wilkins’ standing to take on the role of an executive chairman until replacements are found.

A food maker that found contaminants in its product would immediately instigate a product recall, run an advertising campaign, offer compensation and make good the mess.

When the Australian cricket team was caught cheating, the captain went that week, together with the other players involved. The coach went soon after.

In May last year, AMP told ASIC it had found it was charging some customers for work it didn’t do, theft by another name, and until this week it appears to have done nothing except use its lawyers to mitigate the damage.

It took the public spotlight of the royal commission to spark Brenner and her board into belated action. Chief executive Craig Meller was already out the door and yesterday’s move came too late to be seen as anything other than attempted self-defence by the chairwoman.

The Smith-Gander way

Diane Smith-Gander figures the key to surviving in business is to keep asking questions. “If you don’t keep asking why, you have no chance,” she says.

It’s a characteristic that fits well with another mantra, which she learned from her mother: be open and honest.

“If you lie you have to remember who you lied to and that can become difficult,” her mother told her. Her mother and father also taught her to have a strict work ethic, which she has carried throughout her career.

It’s a career in which she has also taken her life into her own hands, changing career from international public relations to Westpac to McKinsey and back as opportunities emerged.

She made the moves to take her chances.

Her times as a basketballer for Western Australia also taught her the positive power of working in a team. All of this has meant she is not shy to voice an opinion.

Transparency and a directness have been hallmarks of a career that has taken her to the top in corporate Australia.

This champion of corporate diversity proudly accepts she has got to some places through the quota system.

“When I hear someone say, ‘I really want to be appointed on merit’, well, of course you want to be appointed on merit but there is something about offering yourself to be on a board,” she says.

“You need to understand what’s going on there and whether your candidacy does have merit. So I couldn’t care less whether I get in because of a quota because I know I will not offer myself for a board for which I do not have merit.”

She firmly believes corporate Australia needs more diversity and if women can get into the room then “we keep the door open for others”.

Her first job was flipping hamburgers in a shop in Fremantle.

She grew up in Perth after a time in Kalgoorlie, where her maternal grandfather was an underground miner.

Early on she learned a Protestant work ethic and a strong sense of public duty from a mother who was in the Red Cross and a father who was an apprentice boilermaker before becoming a professional sprinter.

She completed her schooling at Melville Senior High School in Perth and in her senior years always thought she would become a lawyer, taking after her uncle, Jim Beattie.

Instead, she studied economics and her first job was at International Public Relations, which took her across the country to Sydney following the firm’s client Mars and their Uncle Ben’s dog food.

She completed masters of business administration at the University of Sydney.

Research and issues management were always more interesting than the marketing side of the job and this took her to PA Consulting, where her first job was to look at addressable markets for potential new entrants to the banking market.

This was set in train by then treasurer Paul Keating, who opened the Australian market to 16 foreign banks.

Smith-Gander worked in the financial institutions group under Vern Harvey and in this role got to meet the folk at Westpac.

Throughout her career she felt she had to be better than her male colleagues to get ahead and, while a champion of diversity, says she is grateful for the role men played in her career.

This includes Frank Conroy, then the deputy at Westpac; Bob Joss, who really opened the door to women in banking in Australia; and then chairman John Uhrig, whom she still greatly admires.

“He was calm, really firm but had no preconceived ideas on any issue and always took counsel on the options,” Smith-Gander says.

Smith-Gander worked her way up the ranks, including time as Conroy’s chief of staff.

Helen Lynch, another pioneer woman, was also a great influence then and in later years one time HR boss Anne Sherry was also.

At the time, women tended to be in support roles, “not the cash register” jobs held by men.

The then retail bank boss David Morgan told her she was not strategic enough and needed more international experience.

She rang an old Westpac colleague Matt Bekier (now boss at Star Entertainment) who was then in McKinsey’s Washington office. At the age of 42, she was one of the firm’s most senior lateral recruits and her eight years at McKinsey changed her career.

At McKinsey, she worked with talented people and learned that “to be successful you can’t leave issues unresolved”.

“You needed to understand the motivation of clients, what they wanted to do and, importantly, to take a position,” she says.

While Morgan was CEO at Westpac, he stayed in touch with Smith-Gander, looking her up on trips to the US and eventually lured her back to the bank.

When Gail Kelly took over from Morgan, Smith-Gander in her words “didn’t do well from the transition” and, in any case, she was keen to return to Perth.

Her mentor, Helen Lynch, talked to her about the advantages of so-called dual-track careers working as a non-executive director, and the rest is history.

But, once again, it was a man who saw her potential. Bob Every, then chairman at Wesfarmers, talked her into joining the board.

She has served as chairwoman of Broadspectrum, deputy chair at NBN and CBH while also sitting on the board of AGL as well as on a list of government and not-for-profit boards.

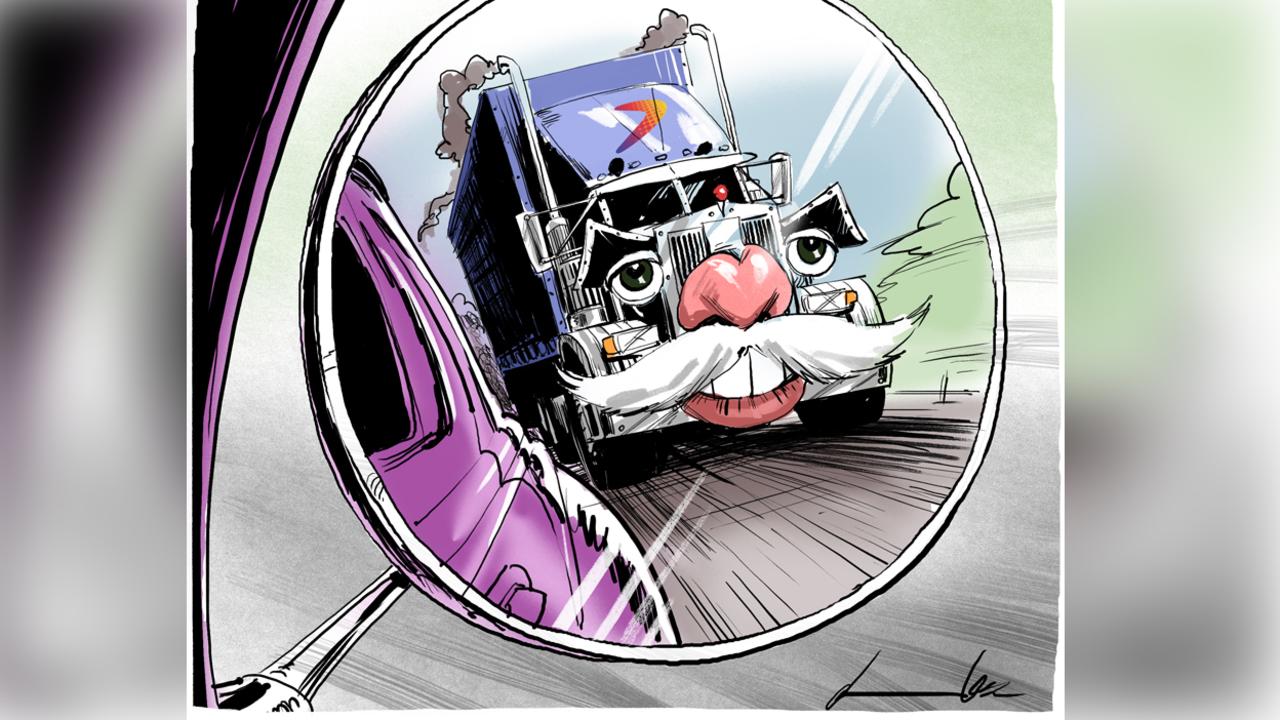

Smith-Gander learned from Every how to smell smoke coming under the door and working out where it was coming from.

This, she says, it is not easy when often “you have no experience in the issue and the challenge for the board is to recognise that there is smoke’’.

“You need an ability to take a helicopter view of the company, show great leadership in setting a risk appetite expressed in set objectives to progress the company in a sustainable way.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout