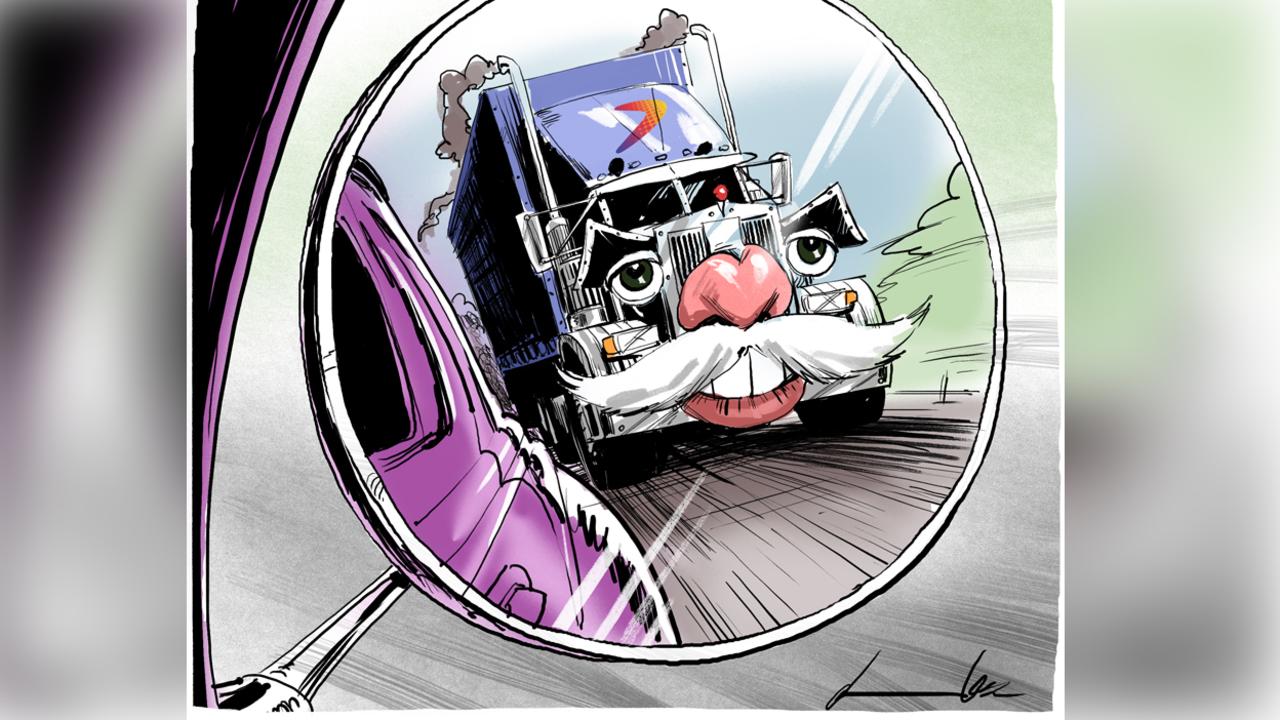

All talk, no action as CBA’s Matt Comyn ignores the problems

When faced with a potentially high-profile consumer nightmare, Australia’s biggest company descended into fiefdom defence.

When faced with a potentially high-profile consumer nightmare, Australia’s biggest company descended into fiefdom defence, petty internal politics and, ultimately, inaction from the boss: that’s how the royal commission neatly portrayed the problem with CBA.

It might be a company on the verge of reporting a $10 billion profit but, on yesterday’s evidence, new boss Matt Comyn has a massive task to reform a fundamentally flawed institution.

Comyn handled proceedings well but commission counsel Rowena Orr kept his most vulnerable side for the end in her examination of consumer credit insurance.

On one hand, Comyn shined as the promoter of customer-friendly policies like ending mortgage broker commissions and consumer credit insurance, but ultimately the consumer’s friend failed to get it past the bureaucracy.

Along the way, he didn’t quite explain just why the bank still has variable pay for sales staff, particularly since this can amount to 10 per cent of total pay and he himself had long ago recommended it be cut to a maximum of 5 per cent.

The commission doesn’t like variable pay or mortgage broker commissions and Comyn agrees 100 per cent. But when asked what he has done about it, the response looked close to a doughnut shape.

The APRA report this year on the bank’s governance failings was circulated to the top 500 managers in hard copy, with a demand for a written response after consulting their teams, with another 4000 staff letters circulating the report in soft copy.

The issue is still being rammed home, with an executive offsite in the next fortnight to further discuss the issue.

The internal audit people at the bank popped champagne corks because finally, after years of being ignored, the APRA review underlined their concerns that they were simply not being heard.

Profits came before customers at CBA. People like retail bank compliance boss Larissa Shafir said she felt validated and relieved because the voice of risk was not being heard and senior executives were not challenging what was going on.

This was in Comyn’s own division, the $10 billion retail powerhouse.

Consumer credit insurance was a product Comyn had wanted to get rid for several years but attempts to get his then boss Ian Narev to take action appeared to fall on deaf ears.

His predecessor, Ross McEwan, was telling anyone who would listen to get out of the game because the one-time heir apparent at CBA was now at RBS in London and saw the issue of miss-selling insurance products explode into a major problem for UK banks.

The problem with the insurance was it was sold to people who were unable to claim because they didn’t meet the criteria for employment and other reasons.

Yet the bank kept on selling and in 2012 then wealth boss Annabelle Spring wrote to Comyn on rumours that he was trying to axe the product and urging him to lay off.

For Comyn, the business was worth $30 million; for Spring it was worth more like $150m and she didn’t have the rivers of gold from mortgage products bringing in $5 billion in profits on $10bn in revenues in a company producing $23bn a year in revenues.

When he took control earlier this year, Comyn acted and axed the product and started a remediation program paying back $16m to 140,000 customers. The money is tiny in the scheme of things but what it tells you about how the CBA was run is huge.

Not only did Comyn run soft on an important customer-friendly issue, but in doing so he and the bank effectively ignored ASIC recommendations on how to sell such products to consumers.

In the last hour of a full day of hearings by the royal commission, the case against the banks was neatly rammed home — they were either deliberately ignorant or just plain ignored the regulator, were driven by corporate greed and pursued policies favouring shareholders over customers.

It is an ultimately unsustainable strategy as the banks have now realised and, hopefully, the competitive landscape will be altered to ensure they will be driven to accept in the years to come.

ASIC serves it up

ASIC’s director’s duty case against advertising guru Harold Mitchell and former Tennis Australia chief Steve Healy ticks all the boxes you might want in terms of public profile. High-profile heads on stakes is part of the game for corporate cops. Governance issues extend way past listed companies and you only have to look to Alex Maley and CPA and the present issues at Cricket Australia to know these organisations have some lessons to learn.

The quick response to the Tennis Australia case is “who cares” and that surely ASIC has more important issues to worry about than the fact the board of Tennis Australia didn’t know there were rival and more lucrative offers on the table than the inside one from Seven Network.

As events transpire, Nine has emerged with the tennis and Seven with the cricket in partnership with Foxtel.

But Tennis Australia had allegedly gone to the trouble in 2014 to get an outside valuation on the rights, which came out at between $148m and $212m — well north of the $100.9m offer from Seven.

That information allegedly was kept from the board and, if that is the case, it is a serious issue and one ASIC should bring to court.

The issues came to light because the board of Tennis Australia had an almighty internal row with one faction supporting Mitchell and one against.

Some high-profile reputations were at rick with the message made clear to organisations across town that they must conform to the law no matter where they sit on the corporate table.

Debt reset for Myer

Myer is finalising new debt arrangements with its bankers amid concerns over its sales performance heading into the key Christmas period.

The retailer has declined to detail existing arrangements with its bankers, who include the big four Australian banks and two Japanese banks.

But the inference is that the company is within existing debt covenants.

The new arrangements will be finalised by the end of next week.

At last count, the company had net debt of $113m but estimates put its actual debt at closer to $2bn when you include the impact of lease obligations.

New accounting rules will force the company to detail its full obligations by the end of this financial year.

The company’s stock price fell as much as 17 per cent in early trade after it revealed first-quarter sales slid 4.8 per cent.

Solomon Lew has used the sales fall to increase his pressure on the board as part of his attempt to get control of the company without actually paying for it.

The equity value of around $360m would be easily absorbed by Lew but he is keen to avoid assuming the full financial debt, including lease payments.

Lew presumably wants to win board control of Myer to monitor how his supplier arrangements with the company are managed.

Myer has come under some criticism for its lack of disclosure and certainly, once its new debt arrangements are set, it would be handy if they were disclosed to the market.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout