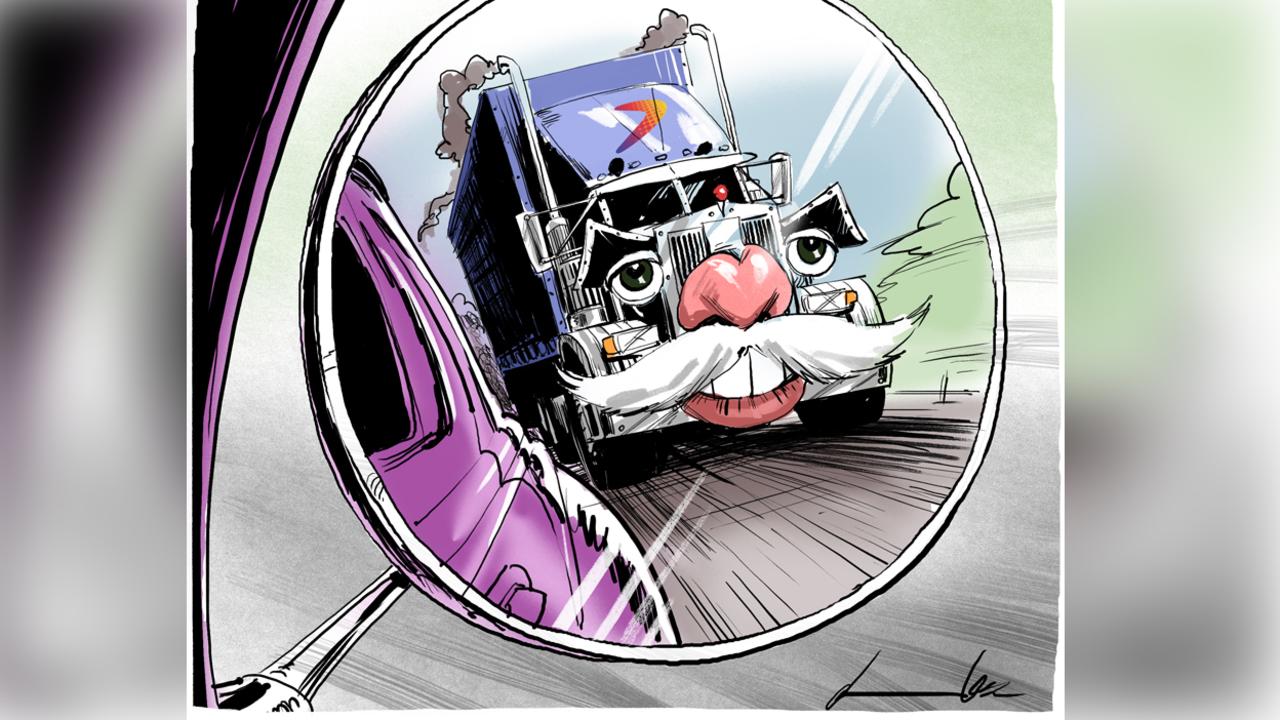

A short-sighted gas intervention from Malcolm Turnbull

It’s one thing to ensure local gas producers play by the rules, but another thing to interfere in the market.

The short-term problem with gas on the east coast is not so much supply as the price and Malcolm Turnbull’s extraordinarily heavy-handed market intervention should at least ensure the local producers are playing by the rules.

As long as the government doesn’t interfere in the pricing process and gas is available to local users at export parity prices, there is an arguable case for the Prime Minister’s dramatic policy, even if others may have urged more caution to let the threats do the job rather than taking out the sledge hammer. To interfere on domestic pricing and exports would be plain dumb.

Even the so-called short-term measures being imposed run real risks, especially if the government was to, say, stop Santos from exporting gas because it is short on local supplies. Santos is the most obvious target because it is short of gas, but Origin and Shell are also on notice not to impose premium prices on the local market just because they can.

Short-term government controls, as those promised, have a habit of lasting longer. More than two decades ago, state and federal governments worked overtime to cut export controls, which underlines the risks involved. Still, spot domestic gas prices are now roughly equivalent to those in Japan and while oil prices are subdued, the danger of higher prices is minimised unless there is blatant profiteering by local suppliers.

If price is the real concern then that should be readily apparent.

The Prime Minister last week ordered the ACCC to monitor the east coast gas market, to ensure prices were not being distorted. But Turnbull clearly wanted to be seen to be doing more and didn’t have the patience to let the ACCC work run its course.

Price is basically a function of supply and demand and longer term the real problem is, of course, supply, with exploration and production bans in place in Victoria and NSW that no one thought probable 10 years ago.

There are, of course, sovereign risk issues in blocking exports after they are granted, but in the scheme of things this is more a danger than a reality.

Last month Turnbull threatened to impose export controls. Today he is following through on those threats with almost unseemly haste, which leaves the local producers nowhere left to hide.

Bonus for turning up

The big executive salary push is to cut long-term bonuses in favour of bigger short-term bonuses paid in stock and it is a total nonsense.

Look no further than fallen mining services star Boart Longyear, which last year paid its new chief Jeffrey Olsen $US554,400 in short-term bonuses. That came on top of a base pay of $US536,154 and in total pay reached $US1.9 million.

So uncertain were the company’s finances that auditors at Deloitte declined to given an opinion on whether the company would last 12 months.

Yet the board, under former BHP executive Marcus Randolph, was happy enough to pay Olsen the bonus even before unveiling plans to talk with debt holders about recapitalising the company — let alone knowing the outcome of those reports.

The bottom line is these bonuses should be paid for extraordinary work, not simply turning up and hitting the pay clock.

Companies treat executive bonuses as essentially fixed pay but it looks better to split the fixed component.

CEOs don’t like long-term bonuses much because they are risky, and who wants to take risks when you can avoid them?

The auditor’s report released in the company’s annual report yesterday was dated February 27, ahead of an announced recapitalisation plan unveiled on April 3 in which debt holders including private equity firms Ares Management, Centrebridge and Ascribe would reduce debt and interest costs. When a company’s auditor declines to give an opinion on the accounts, few would say the company’s performance is good.

In its report Deloitte noted that “we have not been able to obtain sufficient appropriate audit evidence to provide a basis for an audit opinion on this financial report”.

It noted last year the company incurred a net loss of $156.8m and as of December 31 its liabilities exceeded assets by $337.5m.

Deloitte noted the private equity talks, but said “we have been unable to obtain sufficient evidence as to the likelihood that a successful conclusion to the restructuring discussions will be achieved”.

Management, however, still received its bonus.

Dairy mulls cost cuts

If the talk in the dairy industry is right, then next week Murray Goulburn will come up with a new plan to help cut costs and boost farmgate milk prices in order to shore up its farmer base.

The company declined comment other than to say its review of operations is well advanced.

One year ago, MG created havoc in the industry when, after predicting an increase in farmgate prices to over $6 per kilo of milk solids, it slashed them below $5 a kilo.

The action helped cut its milk intake by at least 20 per cent, though this was also due in part to last year’s wretched season, in which heavy rain decimated supplies.

New boss Ari Mervis is expected to unveil his new plan next Monday, and it will include details on which of his 10 plants will be shut in order to accommodate the fact that supplies have fallen.

The industry is speculating the Maffra and Rochester plants in Victoria will go, with a question mark also hovering over the milk plant at Kiewa.

Mervis is new to the game, having started at the company in early February, and an industry outsider who has shifted over from the beer sector.

He has a new chairman in former Ferrier Hodgson corporate undertaker John Spark, who replaced dairy farmer Phil Tracy.

Much of the restructuring work was completed under the reign of former boss David Mallinson who cut head office staff by 10 per cent, or about 200 people.

More cuts are likely.

MG’s share of the local milk production peaked at 37 per cent in the 2015 financial year but has fallen below 30 per cent since, with all processors boosting their share and arch rival Fonterra increasing to over 19 per cent from 17 per cent.

Fonterra’s farmgate price is $5.20 a kilogram, well above MG’s $4.95, which underlines the competitive disadvantage MG faces.

Next week’s statement is also due to underline working capital and other changes to restore the company’s balance sheet and put its finances back into a competitive position.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout