Huawei arrest shows a new Cold War is unfolding

Australia’s economic ties with China could suffer if it was forced to choose sides in the confrontation on the tech front.

The arrest of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou confirms that a new Cold War is being played out in the technology sector.

Business executives in Western countries such as Australia will now have to think twice about using Chinese technology — being forced to make a Cold War-driven choice regardless of the fact that the Chinese technology maybe cutting edge and better value. While Meng still faces extradition to the US on unknown charges, the move by the US Justice Department is believed to have been part of its investigation into whether she was involved in breaching sanctions against Iran.

The move — which comes after governments in Australia and New Zealand have banned Huawei and fellow Chinese tech giant ZTE from supplying equipment for the next generation 5G network, on the grounds that their technology could be open to interference from the Chinese government — raises concerns that the Justice Department has new unspecified information against Huawei, or at least Meng as the company’s chief financial officer, deputy chair and daughter of the company’s founder.

While the issues and allegations have yet to be aired in a court and Huawei insists that it has complied with the law in all the countries it operates in, Australia is inevitably being drawn into a US-led Cold War on the tech front with China.

As the China Daily spelled out in its editorial yesterday, US allies including Australia are being drawn into a Cold War by Washington, pressing its allies to cut ties with Huawei “claiming its equipment poses strong cyber security risks”.

Regardless of whether the concerns about Huawei are justified or not — and Meng has not had a chance to defend herself — the fact that Australia is part of the Five Eyes intelligence sharing pact between the US, Britain, New Zealand and Canada is drawing it into a technology future where the US view of security issues will increasingly influence business decisions.

The red lines are being drawn by the security sector between Chinese and Western technology suppliers.

US-based China watcher Bill Bishop spelled this out in the latest edition of his newsletter Sinocism.

“Any foreign and especially US technology firm that has supply chain reliance on China needs to be deep into planning for reducing that reliance, no matter how hard, painful and expensive such a shift would be,” he wrote.

“Boards of directors of those companies are negligent at this point if they are not pushing the company to do this planning.”

Concerns about Chinese anger at Meng’s arrest have already raised fears that US technology executives could be vulnerable to arrest if they visited China.

While Bishop rejected the idea, he warned that executives should hold off planned visits to China.

“If I were a US tech executive I would delay travel to China or go on a vacation if I was based there,” he said.

Meng’s arrest has capped off a horror week for Huawei, the world’s largest supplier of telecoms equipment which has a long history of operating in Australia, including supplying Optus and Vodafone with their 3G and 4G technology, and supplying services to state governments including NSW and Western Australia.

In August this year the Trump administration passed legislation banning Huawei and ZTE from supplying equipment for government operations.

While Huawei has operated in Britain for years, network giant BT — which has used Huawei equipment for almost 15 years — announced this week that it will not consider bids from Huawei for its 5G network.

This follows pressure by UK intelligence and security officials.

BT also confirmed it would be removing Huawei components from its core 4G technology network although it will continue to use its equipment for other parts of the network.

The decision followed comments by Alex Younger, the head of the UK secret intelligence service MI6, that the government should question Huawei’s involvement in Britain’s 5G roll out.

“We need to decide the extent to which we are going to be comfortable with Chinese ownership of these technologies and these platforms in an environment where some of our allies have taken quite a definite position,” he said.

Yesterday also saw reports from Japan that the government was also set to effectively ban government purchases from Huawei and ZTE over fears of intelligence leaks and cyber attacks.

Japan’s Yomiuri newspaper said the government was expected to revise its procurement policies.

In an interview with The Australian at a conference hosted by ANZ in Singapore in October, New York political scientist Ian Bremmer warned that Australia’s economic ties with China could suffer if it was forced to choose sides in a global “technology Cold War”.

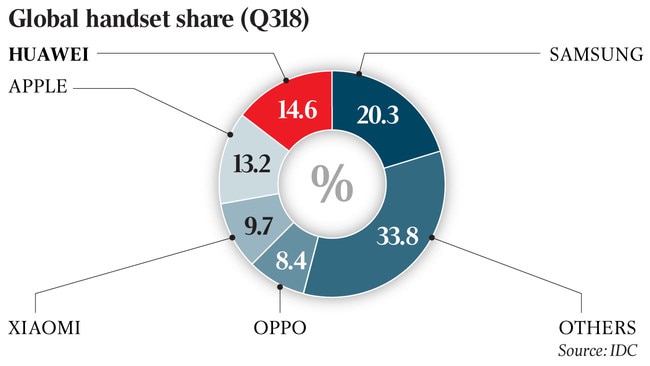

Mr Bremmer, who is president of political risk firm Eurasia Group, said it was increasingly likely that the world would see two different tech systems in future — one dominated by the US and another by China — citing Australia’s decision to ban Huawei from supplying the 5G network as a prime example of the trend.

“Over the next 10 years, it is plausible that we will end up with a fragmented technology system — with two internets, one American and one Chinese, two systems of big data,” he said.

“Countries will have to choose which system they want to be on.” Mr Bremmer said if Australia were forced to choose it would most likely opt for a US-led technology system.

“If Australia has to choose, it would most likely choose the American system because of its American national security orientation, which will probably have negative implications for a lot of your other industries doing business with China,” he said.

“Right now, Australia has a great security relationship with the US and a great economic relationship with China.

“It is not clear, in 10 years’ time, if the US versus China is going to be a big technology play, that Australia is going to be able to do the same.

“If there is a technology war between the Americans and the Chinese, countries like Australia have to choose. And that is really dangerous,” Mr Bremmer said.

“It means they don’t have the ability to be as flexible in hedging between the great powers as they do now,” he said.

“If you have to make a technological choice, it will have economic implications.

“It will obviously have knock on effects.

“If your countries are fundamentally fighting in technology, then probably the Chinese are going to be more interested in sending their tourists to other places.”