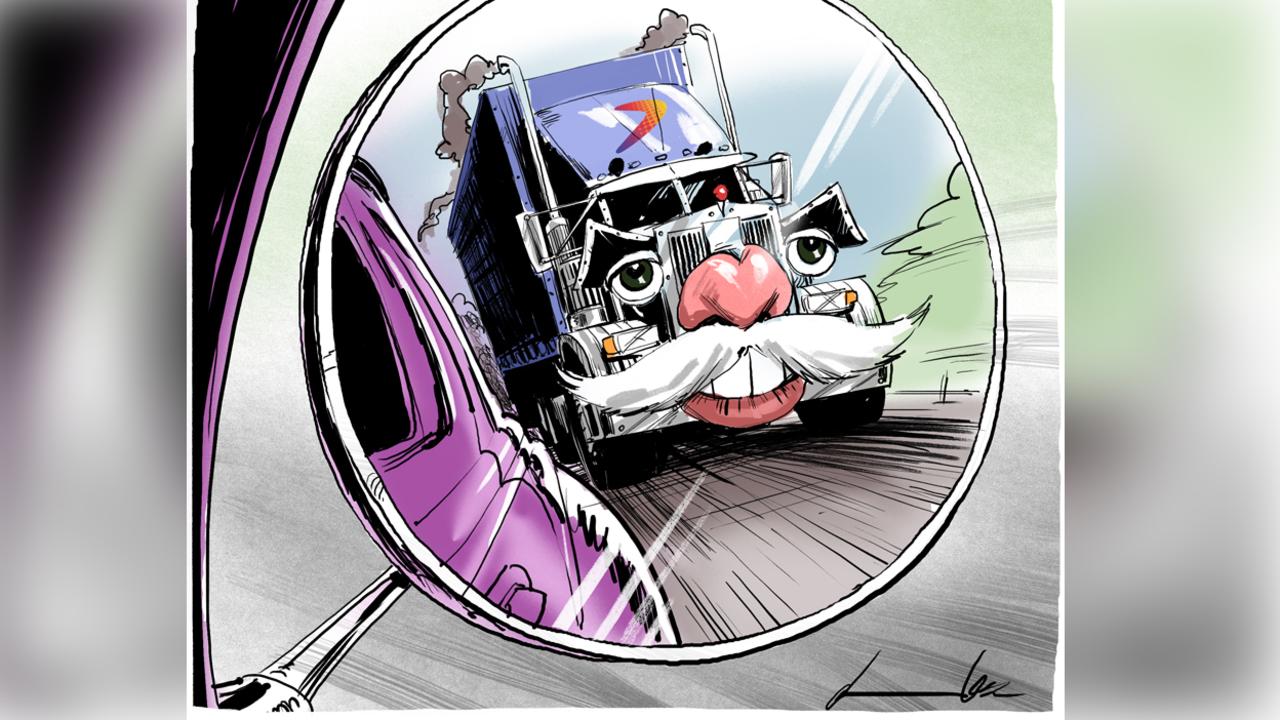

Directors get a wake-up call after Centro case

THE Federal Court has served a timely warning to directors that they are ultimately responsible for the company's financial accounts.

THE Federal Court has served a timely warning to public company directors that they are ultimately responsible for the company's financial accounts and cannot hide behind the advice given by management or the auditors.

Justice John Middleton's decision in the Centro case yesterday was a significant victory for ASIC and indeed for company auditors PricewaterhouseCoopers, given all the non-executive directors made much of the fact they relied on the auditors and management.

PwC's day may still come, with Justice Middleton also presiding over a class action against it, and the company and ASIC are still considering their next moves.

The important point here is the principle that directors are ultimately responsible, and it would not be surprising if all the NEDs escaped bans when penalties are considered in hearings in August.

The court made it clear that the directors acted honestly but negligently, which means the more likely penalty will be a fine, with just an outside change of a lengthy disqualification.

This being the case, an appeal may not be as certain as many considered yesterday.

ASIC wisely limited its target to avoid extraneous attacks.

The decision is one of the most important judgments on directors' duties and, of the three recent ASIC cases, the most relevant to the wider community.

The other two are both before the High Court.

The Fortescue case about misleading the market, and James Hardie can also be distinguished on the facts of the case.

The directors' lobby will justifiably object to some of the judge's prescriptive comments on where directors stand, but it cannot object to the fundamental obligation to understand the company's accounts, how they relate to their understanding of a company's position and a requirement to meet a certain standard of financial literacy.

If this decision raises the bar for public directors, in the scheme of things it is not overly burdensome. Instead, it is more an affirmation of what most people would have read into the law.

This, then, will not bother some comrades within the Australian Institute of Company Directors who prefer to see their role as an advisory function paying $190,000 a year plus expenses with no responsibility.

If this judgment triggers another debate on the role of company directors, that too would be welcome.

ASIC and its former boss, Tony D'Aloisio, have been vindicated in pursuing the high-profile case against the likes of former Centro chairman Brian Healey because the law should be tested and, where necessary, extended.

So far in high-profile board cases, the corporate plod has put in a great performance.

There are two schools of judicial thought on corporate governance: the-buck-stops-here model advocated by Justice Neville Owen in the Bell Group cases, and the liable-only-when-at-fault school.

Justice Middleton has rightly gone for the Owen school.

The law is explicit, but big company directors rightly argue that there is an expectation gap in the community about exactly what they do.

The trouble is they are the perpetrators of the myth of their importance in the day-to-day running of the company, which is odd, given many are washed-up former chief executives who are past their prime on everyday stuff. They have opted for part-time roles and, as such, argue they cannot be expected to know everything going on in the company.

This school argues the role is more about coming to the fore at times of big corporate activity and appointing a new chief executive.

Justice Middleton doesn't necessarily disagree, but he does see signing financial accounts as a pivotal moment in the calender.

Indeed, the way it works is the auditor only signs after the directors do, for the very reason that it is the board -- not the advisers -- who have ultimate responsibility.

The new ASIC boss has signalled he would like to get advisers more involved and in the responsibility tent, because too often snafus happen with no fault being attributable.

Eminent company lawyer Minter Ellison's Bob Austin is proposing a change in the law to remove clauses from company constitutions which specify directors' duties as including management of the company.

This would be aimed at clarifying the position, but even if this amendment was in place at the time of the Centro collapses it would not have excused Brian Healey and his comrades.

Justice Middleton's 186-page judgment was written to focus attention on what he saw as the key principles being outlined in the first few pages.

No doubt the judge is aware that only those intimately involved get much past the first couple of pages.

He went too far in suggesting a director is placed "at the apex of the structure of direction and management of a company", when plainly most NEDs are not even close.

But his rules of engagement should now be distributed to every listed company director.

These rules are: directors should have a rudimentary understanding of the business, become familiar with the fundamentals, should keep informed about its activities, should maintain familiarity with the financial status of the company and its financial statements, and should have a questioning mind.

"A director is not relieved of the duty to pay attention to the company's affairs, which might reasonably be expected to attract inquiry even if outside the areas of the director's expertise."

These are not revolutionary concepts, and few of the more extreme all-care-but-no-responsibility wing of the AICD could find fault with that.

To the extent Justice Middleton has extended the law, it is for entirely rational reasons.

As noted before, while laying down the principles, he has gone a long way short of setting up the NEDs involved for a lengthy session on the disqualified list.

The reverse is probably closer to the mark.

This will disappoint those looking for blood, but in the scheme of things reputations involved must have already taken a tumble, and the key here is to establish principles to set the record straight.

Big Centro trade

JUST while some were reviewing the Centro judgment, UBS took the market by surprise, swapping some 114 million, or 5 per cent, of Centro Retail.

It seems the chance of corporate action is minimal and instead some positions were being swapped among hedge funds, which dominate the share register.

Wagering delay

HOPES of a pre-June 30 decision from the Victorian government on the wagering licence have been dashed, with one unlikely this week.

One of the ministers involved, Warrnambool-based Dennis Napthine, confided yesterday that the decision would come soon.

This had everyone thinking that the Victorian government would stick to its pledge to have an answer by June 30.

The decision is indeed days away. However, it seems more likely it will come early next week.

Tabcorp is the hot favourite to win the wagering licence, while Tattersals is favoured to pick up the gaming machine monitoring role.

The decision would absolve the government from paying a big compensation claim to Tabcorp, which has always maintained it was its licence to lose.