Economic growth slows as housing, spending decline

Weak consumer spending and a downturn in housing construction are the main culprits as the economy slows sharply.

This week’s national accounts are expected to show the economy has slowed sharply, with some estimates suggesting the annualised growth rate of almost 4 per cent achieved in the first half of last year slid to just 1 per cent in the second.

Weak consumer spending and a downturn in housing construction are the main culprits, while the export sector is also expected to subtract from growth.

The consensus forecast of market economists is for 0.5 per cent growth in the quarter, which would generate 2.7 per cent growth for the year.

The Reserve Bank’s latest forecast is a touch higher at 2.8 per cent, but a number of economists expect a much softer result.

The ANZ’s head of Australian economics David Plank predicts growth of just 0.2 per cent in the December quarter, while Commonwealth Bank’s chief economist Michael Blythe expects a quarterly rise of between 0.25 and 0.5 per cent.

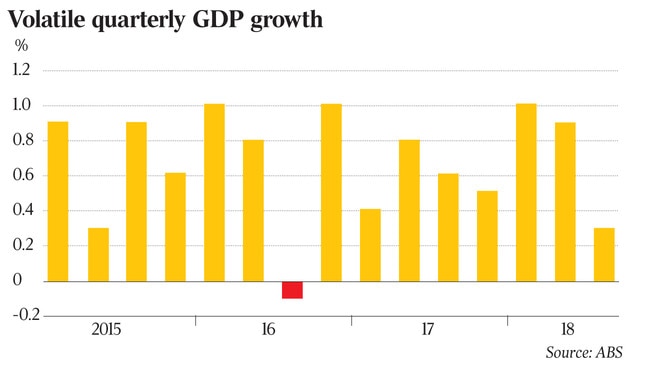

All estimates imply a significant loss of momentum from the first half of 2018, when GDP bolted ahead by 1 per cent in the March quarter, followed by a 0.9 per cent increase in the June quarter. The slowdown began in the September quarter, when the growth rate dropped to 0.3 per cent.

There are still some key inputs to the December quarter’s GDP to be unveiled. Unpredictable swings in inventories can have a big impact on the final figure, as can volatile public sector spending.

The quarterly GDP figures themselves have a history of volatility. In 2016, for example, growth of 0.8 per cent in the June quarter was followed by a 0.1 per cent contraction in the three months to September and then by a surge of 1 per cent in the final three months of the year. The quarterly swings in 2015 and 2017 were only slightly less extreme.

Behind that volatility, the economy has been averaging 2.6 per cent annual growth since the global financial crisis struck a decade ago.

The slowdown over the past six months punctures the dreams of a lift in the growth rate above 3 per cent, which was entertained by the Reserve Bank among others until six months ago.

It is likely to leave the economy growing at a similar rate to the post-crisis average.

That would still be respectable among advanced nations, which the IMF expects will only average growth of 2 per cent this year and 1.7 per cent next. But it is less than Australia has been used to. If the more pessimistic assessments prove correct, growth would drop to the low twos.

The slowing in the latter half of 2018 reflects some important change. Both the housing construction boom and the preparedness of consumers to lift spending faster than the rise in their incomes helped the economy to adjust to the end of the resources boom.

The housing boom was stoked by the RBA’s run of rate cuts from November 2011 to August 2016, which brought the benchmark cash rate down from 4.5 per cent to 1.5 per cent. Standard variable mortgage rates came down from almost 8 per cent to just above 5 per cent.

Although housing construction is a relatively small component of the economy (about 6 per cent), it has a larger spillover to both retail spending and building materials manufacturing.

The boom was also propelled by strong population growth in Melbourne and Sydney. The services industries of those cities have enjoyed rapid growth, particularly tourism and education.

State governments have responded with a big lift in infrastructure investment that has also supported employment.

Both Melbourne and Sydney have absorbed that population growth, with unemployment rates dropping to historic lows of around 4.5 per cent.

The downturn in housing markets in these two cities, which gathered pace over 2018, has not stopped the music, but it has slowed the tempo, particularly in Sydney.

Economists expect the national accounts to show household spending was soft in the December quarter. Retail sales were weak, including a rare fall in Christmas sales, and car sales have also been falling. Consumer borrowing fell in the quarter.

Household incomes have been crimped by unusually low wage growth since 2016, but consumers have until now been prepared to reduce their savings in order to maintain spending.

There is debate among economists about whether that reflected a “wealth effect”. Were households confident to lift spending because their houses were rising in value? In which case, are they now likely to cut back because house prices are falling? The RBA is sceptical about this. Governor Philip Lowe will set out his views in a speech tomorrow, but is likely to emphasise the more direct link between housing turnover and consumer spending on furnishings and household goods.

The RBA does believe the depletion in household savings has almost run its course, and expects consumer spending will rise by no more than incomes in future. With softer consumer spending and a downturn in housing construction, the economy loses two of the key supports that have sustained growth for the last five years. This is being offset to some extent by rising investment by non-mining companies and by state government spending on infrastructure.

The resources sector is also expected to start lifting its investment over the next year, which would be the first time since 2012.

Last week’s official business investment survey was positive about the outlook, although estimates made in February about plans for the next financial year are unreliable.

There is still a considerable amount of work being done on state government infrastructure, and this will continue to support employment in the construction industry, although a number of the biggest projects will approach completion over the next two years.

The key issue for both the RBA and the economy at large is the extent to which the slowdown over the last half of 2018 reduces employment growth. Thus far, economic growth of around 2.6 per cent has proven consistent with strong employment growth.

Employment remained firm over the last half of last year and through to the latest January report. Job vacancies are at a record high and although job advertising has tapered off in recent months, it remains elevated.

The dynamic impulse of strong flows of migration, tourists and students remains in the major cities. Employment traditionally lags trends in output — it takes time before employers act to adjust the size of their workforce.

If the more pessimistic assessments of growth are correct, unemployment would be likely to start creeping higher over coming months. However, there is no hint of that yet.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout