We can thank the GFC for forcing top lawyers to really earn those flashy vehicles

WITH the benefit of hindsight, it is starting to become clear that the global financial crisis was not all bad.

WITH the benefit of hindsight, it is starting to become clear that the global financial crisis was not all bad. Without a disruption of such scale, lawyers around the world would still be on easy street. And who would want that?

It might have taken the near-collapse of the global financial system, but the domestic and global markets for legal services are now healthier places.

Consumer sovereignty has been restored.

The distortion that once placed BMWs in the garages of too many overpaid lawyers is now a thing of the past.

There are still plenty of flashy cars in the basement carparks of the nation’s legal precincts, but the impact of the GFC means those mobile status symbols are now far more likely to be well earned.

By forcing corporate Australia to focus intensely on cost control, the GFC killed off the last vestiges of the days when general counsel were allowed to be lazy.

Instead of doling out millions of dollars in shareholders’ funds to the same old law firms, the top in-house lawyers started demanding big savings.

To achieve that, they encouraged competition from new, innovative players who were the first to see an opportunity amid the gloom.

That simple fact, repeated by countless general counsel around the world, has triggered an upheaval that is still being felt.

This disruption to the established order truncated many careers and led directly to the erosion of professional conceit. In the post-GFC world, rewards flow to those with the healthiest recognition that the client — not the law firm — is king.

Initially, the benefits of this change went to the new, nimble players with very low fixed costs and flexible business plans. Then the established mid-tier players got in on the act, stealing the lunch of those big firms that were still struggling with a cost structure that was designed for the past.

But if anyone thinks the days of the big law firms are over, they have severely underestimated the brainpower of those people who have scrambled to the top at these firms.

They have no intention of going quietly.

Their fierce determination can be seen by the severity of the job losses — and reduction in partnerships — that were identified in The Australian’s latest survey of the leading firms.

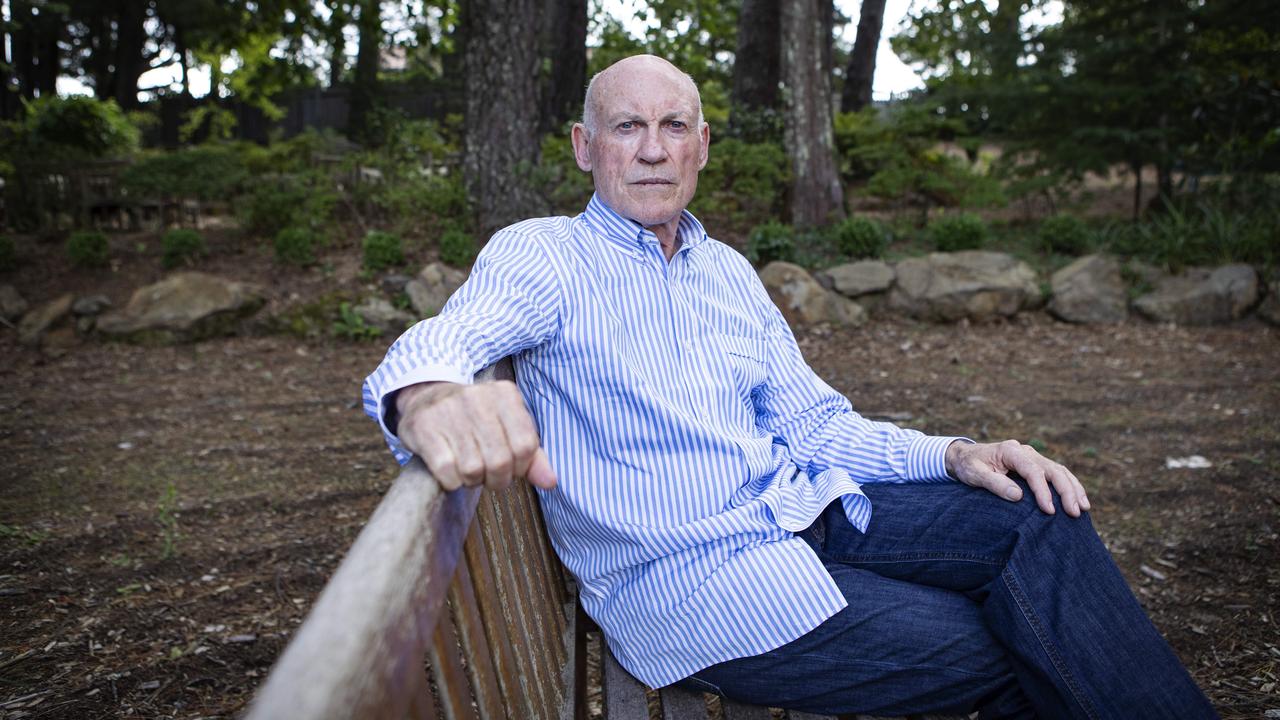

The decision of DLA Piper to recruit an insurgent such as Stephen Allen is further evidence of the changed mindset that is sweeping the profession. Allen’s ambition for DLA Piper is huge: he wants nothing less than a re-engineering of the way this global giant meets the needs of its clients.

DLA Piper is not alone. It is now almost normal for big firms to present clients with a choice of where they would like mundane legal processes to be undertaken — Bangalore, Manila or maybe somewhere in South Africa.

There is, of course, nothing to prevent corporate clients from tapping into this global outsourcing network themselves, but in Allen’s assessment, companies have other things to do and might not have the “bandwidth” to supervise and manage the coming disaggregation of many legal services.

But “bandwidth” is what big law firms have in bulk. The law firm of the future might well find itself spending a large amount of time — and making a large amount of money — acting as project manager for clients looking for the best deal.