Why Australia is a world champion for home prices

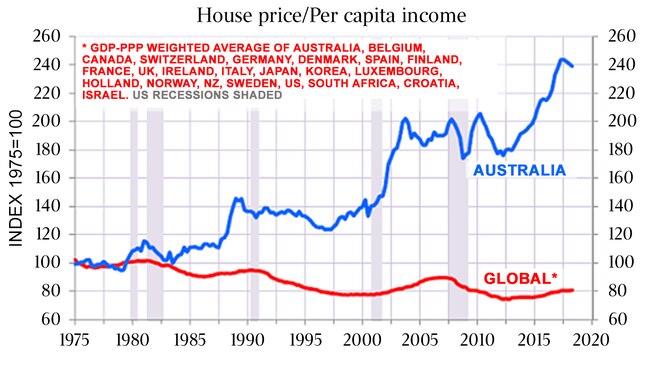

We need to talk about this chart.

It is a truly astonishing thing, this chart – it’s one of those graphics that you look at and think: “Wow. Surely there’s some mistake.”

To put into words what you can see: Australian house prices, relative to income, have increased almost two and a half times over the past four decades while in the rest of the world, on average, houses have become cheaper.

Houses getting more and more expensive all the time — the stone that Australians have dragged behind them these past 40 years — is not what usually happens.

Independent analyst Gerard Minack produced the chart last week from, as he makes clear, data from the Dallas Fed, the US National Bureau of Economic Research and his own analysis.

It’s an index rather than actuals, rebased to 100 in 1975, so it could just be that Australia began from a much lower point in that year than everybody else and we’ve just spent 43 years catching up. But we don’t really believe that, do we?

Many people, perhaps most, will look at the chart and declare: “Aha! See – Australia does have a housing bubble, and it’s all going to come to grief right now, you just watch!”

And yes, maybe it is evidence of a bubble that is about to burst spectacularly, but you would have thought that in 1988, and in 2003. After those two previous peaks that followed steep rises, house prices did fall – 12 per cent in 1989-90, 4 per cent in 2004 and then 10 per cent in 2008-09 - but they recovered fairly quickly.

It’s clear looking at the chart that, relative to incomes they were merely flat for a decade or so after those two huge bubble-like rises in the late 80s and early 2000s that you might have thought would herald something far worse.

The other thing to note about the chart is that there are a lot of very different experiences inside the global average. Japan, for example, has had a horrible time since 1990 and dragged down the average. Spain, Ireland and Italy have had huge busts as well.

The other English-speaking countries – UK, Canada, New Zealand and the United States – have seen large house price increases relative to incomes, and the difference between Australia and those “Anglo” countries is much smaller. But we are the world champions.

So two questions present: why did that happen, and what happens next?

The first is easier to answer than the second (mainly because it concerns the past rather than the future) but the reasons are complicated, and mostly have to do with government policy failure and negligence rather than a national desire to pay more for a house than anyone else.

It seems counter intuitive, to say the least, that one of the planet’s largest and most sparsely populated land masses should have a shortage of land and houses, but that’s what has happened.

First, governments used to build or finance tens of thousands of houses each year from the 1950s to 1980s, but then they stopped. It was partly due to other demands on the budgets, but also due to economic rationalism in the 80s that decreed “private sector good, public sector bad” and led to wholesale privatisations, including of public housing.

Also local councils changed the way infrastructure for new estates was financed. Instead of debt repaid with rates, they moved to upfront charges on developers, which made house and land packages much more difficult to finance.

And finally, inner suburban councils tightened planning laws to prevent higher density, as existing homeowners sought to keep their neighbourhoods the way they were.

And as we know, there have been many attempts since Whitlam in the 70s to encourage decentralisation – that is to get industries and people to relocate to regional areas – but all of them have failed; Australia remains one of the world’s most urbanised nations. Everyone, including migrants, wants to live in the east coast cities.

Other government policy mistakes include negative gearing and first home buyer schemes, both of which encourage demand and subsidise price.

The fact that Australia also has the highest household debt to income ratio in the world is an effect of high house prices, not a cause; Australians don’t have some kind of extreme propensity to borrow, they simply have had to, and in the process, have had to devote a larger proportion of income to servicing mortgages than anyone else.

One side-effect of that has been the most profitable, and lazy, banks in the world, for the simple reason that they corner the largest slice of household incomes. In the US, the most profitable companies used to be carmakers; Australia’s all went broke. Now the most profitable US company is a telephone maker; none of them got off the ground here.

So what happens now?

The short answer is: I have no idea, although I think we can rule out further increases in prices for a while.

In fact, if history repeats, house prices will be flat for a decade, at least relative to incomes, and probably in real terms as well. After the 1989 bust, it took nine years for real house prices to return to the previous peak, after falling 12 per cent in year one.

Will this time be worse than that? So far, after one year, the national decline is 6 per cent. In Sydney it’s 8 per cent; in Melbourne 5 per cent.

However, returning to the chart at the start of today’s column, that 1989 peak had prices relative to income at just 40 per cent above 1975 levels, and still only 40 per cent above the rest of the world.

Now it’s 140 per cent above 1975 and 160 per cent above the global average.

Then again, in 1989 mortgage interest rates reached 17 per cent; now they’re 3.5 per cent. Big difference. Against that, credit is very tight, even though it’s relatively cheap.

Meanwhile, population growth remains strong so demand for housing will be underpinned. Against that state governments are finally throwing some money at infrastructure, including regional fast rail at last, and local councils are allowing higher density suburbs, so supply could exceed demand for a while.

Like I said, I don’t know.

Maybe Australian houses will become much more affordable (hooray!). Then again, the RBA could cut rates next year and prices could starting rising again (hooray!).

Alan Kohler is the publisher of The Constant Investor