The year capitalism started losing people: why profit is not enough

Capitalism started losing people in 2018, especially women and millennials. Profit is no longer enough.

This time last year I wrote a column headed “The four great bubbles of 2017”, to end the year.

It told the stories of four booms/bubbles: the Chinese consumer boom, cryptocurrencies, artificial intelligence and lithium through the three top-performing stocks on the ASX that year (Bubs Australia, My Fiziq and AVZ Minerals) plus ethereum, at that time the second-biggest cryptocurrency after bitcoin.

Their gains in 2017 were all in the thousands of per cent — 10-baggers one and all — and they truly embodied the spirit of the year. The MSCI global index returned an exceptional 20 per cent, led by the US techs and, while the ASX 200 managed just 7 per cent capital growth, held back by the banks, the Small Ordinaries returned 16 per cent and the mid-caps even more, 18 per cent.

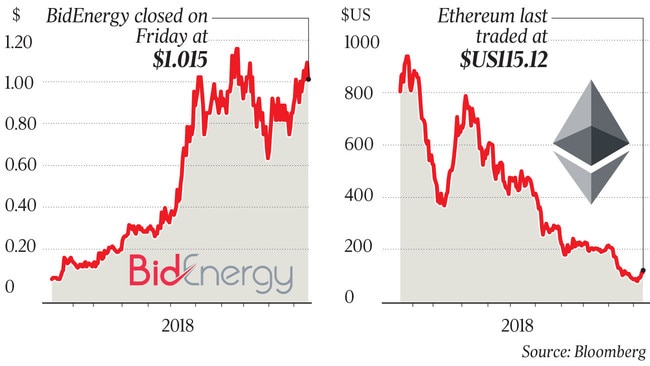

But 2018 has not been so kind to the 1000+ percenters of 2017, or anything else for that matter: the greatest proportion of global assets in history posted negative returns, the ASX has fallen 8 per cent and produced only one 10-bagger: BidEnergy, up from 5c on January 1 to a bit more than a dollar today, a 20-bagger.

And as it happens, this company embodies part of the new zeitgeist: BidEnergy has a cloud-based platform that checks electricity bills and sets up auctions between suppliers to get prices down. It’s still burning cash, but with a $100 million market cap, CEO Guy Maine and his chairman James Baillieu (61 million shares) are looking, and no doubt feeling, great as they enter 2019.

Last year’s 10-baggers were all dogs in 2018. One of them, ethereum, was a 10-bagger the other way: from a peak of $US1346 in early January it is now $US93, less than a 10th of what it was. Bitcoin, the one everyone knows, peaked on December 17 last year and has fallen 83 per cent.

Meanwhile, AI avatar app company My Fiziq’s share price has fallen 75 per cent. Lithium hopeful AVZ Minerals is down 70 per cent and baby-food exporter to China, Bubs Australia, is down 30 per cent.

None of this means the four themes embodied in these things — cryptocurrencies, food exports to China, artificial intelligence and lithium — are finished or that those companies and ethereum won’t stay on the journey. Who knows?

But what their fates this year show is that the future now has a different discount rate.

That is, the main thing that happened in 2018 was the de-rating of investment assets: the multiple applied to future cash flows was reduced. The less likely that future cash flow, the greater the reduction (see ethereum, My Fiziq and AVZ Minerals).

Even reliable cash flows are going for knockdown prices: rent on a nice place in Strathfield, for example, along with all Sydney and Melbourne real estate, dividends from Commonwealth Bank, and all the banks for that matter, or interest payments from the US government.

In simpler terms, we are in a bear market — in property and equities, in fact in everything: 2018 had the greatest proportion of assets decline in history, more even than in 1931.

To guess how long this might go, we have to examine the causes, which are varied and unusual.

Australia’s property bear market is relatively simple to explain: real estate is an investment asset that is always at least 80 per cent geared, which means the availability and price of credit determines the market. In 2017-18, the price of credit didn’t change, but the availability did, drastically and deliberately (APRA did it). Or rather, cheap availability dried up; credit is always available at a price.

There are two reasons for the bear market in equities: first, the tape they are measured with — the global risk-free interest rate, aka the US Fed funds rate — went up so they went down, and second, and less tangible, the engines of capitalism, corporations and right-wing political parties started blowing smoke.

Having kept the funds rate at zero for seven years after the GFC, the Fed has raised it nine times since December 2015, including four hikes this year.

Fed tightening almost always leads to equity market de-rating because the discount rate for working out the present value of future cash flows goes up accordingly.

The “almost” applies only to 2017: despite three Fed funds rate hikes in that year, the US S&P 500 rerated powerfully, rising 19.5 per cent, and the Nasdaq rose by even more, 28 per cent, and within that the FAANGs (Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Google) lifted even more still, about 50 per cent.

It was a concentrated version of the 1990s dotcom optimism, and it ended this year. The Nasdaq finished 2018 roughly where it started thanks to a 1987-esq October dump of 15 per cent.

Which brings us to my second reason for the bear market: the facade of corporate capitalism has cracked, and Facebook has been at the forefront of that for most of the year.

The Financial Times’ legendary economics columnist, Martin Wolf, recently wrote that the conventional view of the role of companies dating back to Milton Friedman — that their sole purpose is to make a profit and to maximise shareholder value — is no longer enough. This idea has been embedded in the remuneration systems of most companies, encouraging executives to focus purely on increasing profits and share prices.

In Australia this year, we have seen that system come crashing down in the royal commission on misconduct in financial services, and then huge first strikes against Westpac, NAB and ANZ, but Wolf’s column tells us it isn’t happening just here.

Profit is not in itself a business purpose: it’s a result of achieving the purpose, whatever it might be, such as making cars, disseminating information or transporting things.

The focus on profit and shareholder value means companies are serving only those who are least committed to them: shareholders. Unlike employees, suppliers and the communities in which the companies operate, shareholders, says Wolf, “can divest themselves of their engagement in the company in an instant”. That is, sell.

At the same time, the political wing of the corporate classes, conservative political parties, have also substantially lost their way in my view. The reasons for this are beyond me, and beyond the scope of this column, but it is patently true, here and everywhere else.

For whatever reason, it seems to me that capitalism started losing people in 2018, especially women and millennials.

To get them back, and eventually have future profits valued as they once were (that is, to reduce the discount rate for their net present value), companies will have to redefine their purpose, and profit alone will no longer cut it.

Alan Kohler is editor-in-chief of InvestSMART.