Marxism and central banking

That led directly to the October Revolution of 1917. On October 23 the Bolshevik majority in the soviet voted for armed uprising and two days later Trotsky and Lenin led the final assault on the Winter Palace and the capital fell to the Bolsheviks.

It’s easy to forget now, with the benefit of hindsight that includes the ignominious collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, what an optimistic moment that was.

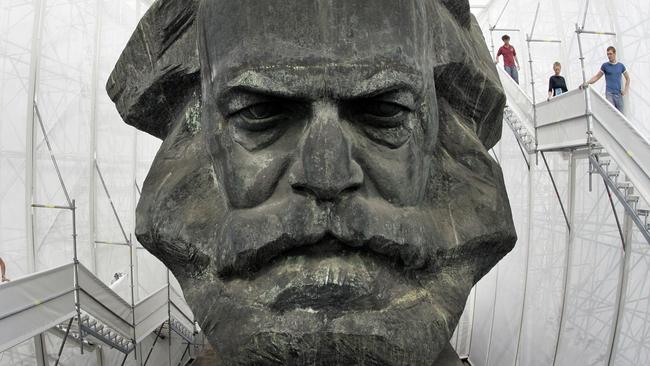

The Russian Revolution had arisen from the Utopianism of Karl Marx, which in turn came out of the French Enlightenment and the inequality of the industrial revolution. In the early 20th century communism seemed the best hope for the world, and for decades after that western intellectuals were still on board.

Marx had proposed that economic perfection was possible — no scarcity, no inequality, plenty for all in equal measure — and his work showed it, in theory. The men who led the Bolshevik uprising 100 years ago this month were idealists; they only became monsters later.

One of Marx’s central ideas, apart from common ownership of the means of production, was the “labour theory of value”, which holds that the economic value of a good or service is determined by the amount required to produce it, rather than the use that the owner gets from it.

We know now that as actual economic policies they didn’t work, and the efforts to force them to work helped kick off the most vicious 50 years in human history, with a succession of tyrants attempted their own versions of perfection, often corrupting Marx.

Mao Tse Tung’s version of Marxism focused on cultural and political perfection, likewise Pol Pot. The Kim dynasty in North Korea are still at it, although they’ve settled into old-fashioned despotism. Hitler was focused on racial perfection.

And in Russia Stalin became the inevitable, brutal outcome of Lenin’s and Trotsky’s dictatorship of the proletariat.

All of the 20th century’s attempts at perfection — economic, racial, political, cultural — ended in failure and misery. Hitler overreached, Mao was incompetent and the Soviet Union simply ran out of puff.

The reason for raising all this today, apart from this month’s centenary, is to suggest that humanity has not yet recovered from the destructive pursuit of perfection.

I’m talking mainly about economics. We moved on long ago from the idea of racial purity, (although it lives to an extent in identity politics), and in the midst of a debate about same sex marriage in Australia it’s clear that the old rules of society have become beautifully untidy.

But the ghost of Karl Marx still haunts economics — not Marxism, but the idea that there is such a thing as the perfect economy, if only the right levers would be pulled by benevolent rulers (central banks).

Marx believed that capitalism’s imperfections would lead to its collapse, but it has turned out that the opposite is true: it’s the imperfections and mistakes that make the market economy strong.

But here we are, nine years after a big mistake, and capitalism’s rulers are still pursuing Perfection Through Policy.

Specifically the stubborn adherence to the Phillips Curve is reminiscent of the Soviets’ adherence to central planning and Marxists to the labour theory of value.

Central banking is another form of central planning, and the Phillips Curve is another form of LVT.

The Phillip’s Curve, invented by the Kiwi economist Bill Phillips in 1958, describes the supposed inverse relationship of unemployment and inflation — that is, that the volume of labour, expressed as percentage of the workforce without a job, determines the prices of goods and services.

It still underpins central banking, and like LVT it doesn’t work.

Faced with the inconvenience of full employment combined with low inflation, central banks press on, trying to get inflation up by getting unemployment down even further, and in the process only succeed in inflating asset bubbles.

Does any of this matter? After all, a kind of perfection has been achieved: strong employment and great wealth. So what if inflation is less than 2 per cent?

The problem is that wages growth is even less than inflation in most developed countries and the level of debt, especially in Australia, is at a dangerous and unsustainable extreme.

Like Marxism the Phillips Curve offers a false neatness where neatness isn’t possible. Central banks are now stuck between waiting and hoping for it to work and searching for a new theory that explains prices. They should try capitalism.

* Alan Kohler is the Publisher of The Constant Investor

Yesterday was the 100th anniversary of Leon Trotsky’s election as president of the Bolshevik-dominated Petrograd Soviet and the formation of the third coalition government of Russia following the abdication of Nicholas II in March.