Scott Morrison and budget tax cuts: no meat in tax sandwich

This year’s cuts will be about politics, not sound policy.

In a moment of candour in 2003 that quickly entered the political lexicon, former Howard government minister Amanda Vanstone criticised her own government’s tax cuts as worth little more than a “milkshake and sandwich”.

These days, especially in inner-Sydney and Melbourne, it’s impossible to get a milkshake and sandwich for much less than $10, which is about the maximum weekly tax cut taxpayers might expect each week from the Turnbull government’s May budget.

The government’s tax cuts will be miserly to the point of embarrassment unless it dumps the promise to return the budget to surplus in 2021.

In a country like Australia that relies excessively on income tax, cutting them becomes painfully expensive.

The modest improvement in the budget outlook unveiled by Scott Morrison last month has chins wagging about the first round of serious income tax cuts for almost a decade.

All taxpayers have had since then is a ham-fisted rejigging of the income tax scales by the Gillard government in 2011 as “compensation” for the carbon tax that no longer exists. More on that later.

Thanks to a stronger than expected global economy, the cumulative bottom line over the next four years has improved by about $6 billion. If the Turnbull government decided to spend double that amount on personal income tax cuts, what could we expect?

Expert budget forecaster Chris Richardson at Deloitte Access Economics has done the maths, estimating it would cost about $12bn over four years to lift the second-highest income tax threshold by $3000 to $90,000, and the next highest threshold of $37,000 to $40,000.

For anyone earning more than $90,000, which is well above the median income for full-time workers, they could look forward — wait for it — to an extra $540 a year, or $10.38 a week.

People earning less than $87,000 (the overwhelming bulk of taxpayers) would have an extra $7.79 a week to spend. Maybe enough for a sandwich without the milkshake.

There are countless other combinations, of course.

If the government decided to cut income tax by $20.8bn, well and truly blowing out the budget absent some freak boom, it could shave the 32.5 per cent income tax rate, which currently applies to earnings between $37,000 and $87,000, to 30 per cent.

Now we’re talking enough to buy a fancy French brie and ham baguette with a kale, beetroot and wheatgrass juice on the side. Such a move would save anyone earning more than $87,000 just over $24 a week.

The first option, though, as Richardson astutely observes, is “cheaper, yet delivers more to swinging voters”.

Moreover, the political class is loath to cut rates as opposed to lifting thresholds.

Rate cuts make tax changes permanent because rates are impervious to inflation. Threshold increases by contrast give politicians the opportunity to present the winding back of unlegislated bracket creep as a “tax cut”. Income tax thresholds are indexed in many European countries to limit this fraud and briefly were in Australia, too, in the 1970s.

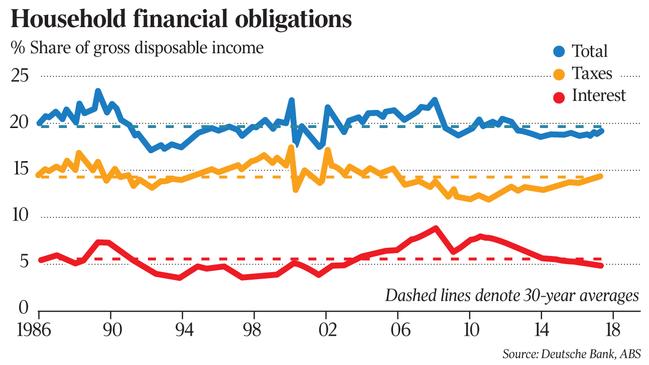

“Households have been in aggregate progressively handing back the Howard/Costello and early Rudd tax cuts in the form of bracket creep for some time now,” says Deutsche Bank’s chief economist Adam Boyton, who estimates the tax burden is in effect now back to where it was in 2006.

The sort of fiddling at the edges taxpayers are likely to see in May will do nothing to improve the economy’s prospects. It will be about politics, not sound policy-making.

In any case, the Medicare levy is due to rise by 0.5 percentage points from July next year to help pay for the National Disability Insurance Scheme. That change would increase tax by $8.36 a week for someone earning $87,000. That is enough to more than wipe out their tax cut from the more likely, threshold-tweak option outlined above.

Beneficial, simplifying tax changes could be made by a government that had guts, however. For instance, the Gillard government’s decision to triple the tax-free threshold to above $18,200 was economically stupid.

Given a certain revenue need, a high tax-free threshold forces all other marginal tax rates to be much higher, which blunts the incentive to work, boosts the incentive to avoid tax, and provides nice little $18,200 buckets into which wealthy families can pour free distributions.

It would be better to abolish the tax-free threshold entirely, and use all the extra revenue to reduce marginal tax rates.

Taxing all income at, say, a 20 per cent rate up to $90,000 would be meaningful, with the power to improve people’s lives and the economy’s growth potential to boot.

To the extent such a reform weren’t revenue neutral, a government could pare back superannuation tax concessions for the over 60s.

In 2006, the Howard government in a fit of madness exempted the earnings of superannuation funds for the over 60s from any income tax at all. Everyone under 60 pays a flat income tax on their super fund earnings of 15 per cent.

It’s a birthday present that has wreaked havoc on the complexity and equity of Australia’s tax transfer system.

Taxing everyone’s superannuation fund at the same low, concessional rate would bring in billions of extra tax revenue and allow the government to slash unusually high rates of personal income tax Australians face.

At a stroke the living standards of the bulk of people, which have been falling in recent years, could be improved without hurting the economy’s prospects.

Unless the government makes serious inroads into cutting spending, though, as advised by the 2013 National Commission of Audit, tax cuts that aren’t revenue neutral just kicks the invoice for government spending into the future.