Broker transparency needed to clear up loans confusion

It’s easy to criticise the finance industry: at 9 per cent of the economy, by far the biggest industry, it’s a fat target.

It’s easy to criticise the finance industry: at 9 per cent of the economy, by far the biggest industry, it’s a fat target.

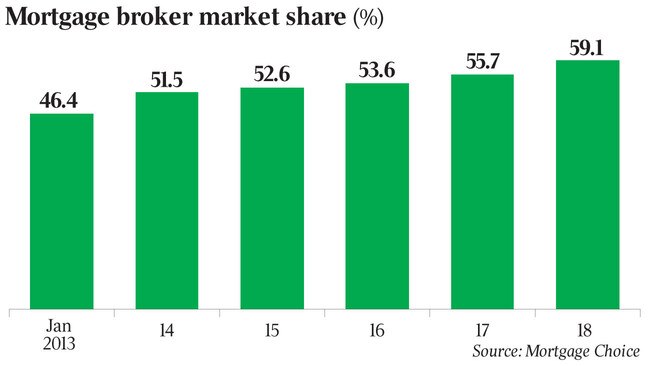

The royal commission threw fuel on the fire, but as the smoke starts to clear it’s the nation’s 20,000-odd mortgage brokers that look to have been seriously singed.

Of the 76 recommendations of the Hayne royal commission, the only one with teeth — both economic and political — was a prospective ban on both upfront and trail commissions paid by lenders to brokers.

But regulation that tries to stamp out practices that have emerged naturally will always face an uphill battle. The consequences could be worse than the problem.

Brokers perform an economic function, bridging the information gulf between lenders and borrowers, and reducing paperwork for buyers. Lenders who rely on brokers won’t necessarily discount their loans for customers who choose to borrow from them directly because brokers in turn would shun their products.

About 25,000 loans a month are written by brokers across Australia — that’s three federal electorates’ worth of interaction every year. Trying to finetune how they are paid will have costs to taxpayers of enforcing the ban.

Labor has backtracked on a promise to implement every one of the Hayne recommendations, instead suggesting capped, upfront commissions.

Senior officials have warned that consumers might end up paying twice if Kenneth Hayne has his wish, bolstering banks’ oligopoly profits even further. They’ll pay an upfront fee all right, but who knows if banks will lower their interest rates to compensate?

The appeal of Hayne’s proposed change is intuitive: upfront percentage commissions (about 0.6 per cent on average) incentivise brokers to encourage borrowers to take out bigger loans, and to use lenders who pay the most commission. The amount of labour effort required by brokers per loan surely doesn’t vary much, if at all, with the size of the loan.

Trail commissions in particular — the approximate 0.2 per cent a year paid by lenders to brokers for the life of the loan — appear to be “money for nothing”, as Hayne himself quipped.

Yet it’s not so easy. It would be difficult to prove that banks had reduced their interest rates to compensate borrowers under a new regime of upfront fees.

Borrowers pay for mortgage brokers one way or another. Making them appear less affordable could undermine competition in a way that could even lift borrowing rates.

Even the fifth biggest player in the mortgage market, ING, writes about 80 per cent of its new loans through mortgage brokers.

“By distributing loans through brokers, smaller lenders have on average increased their market shares by 1.55 percentage points,” the Productivity Commission concluded last year in a review, suggesting they would each need an extra 118 branches to maintain their share without the brokers. Paying a commission of a few thousand dollars to a broker is much cheaper than hiring full-time sales staff on $150,000 a year each — the going rate, according to the commission.

The government has also rejected the idea of scrapping commissions in their entirety. Whoever wins the election in May, it seems trail commissions will go, but some type of upfront commission will remain.

Even trail commissions aren’t necessarily the devil they might seem. They emerged in the 1990s so lenders, especially smaller ones without branch networks, could spread the cost of writing loans over a greater period of time.

They encourage brokers to ensure borrowers are in a loan they can afford: if borrowers refinance, brokers lose the forthcoming trail commission. Scrapping trailing commissions would also mean bigger upfront commissions and an even greater incentive for brokers to write new loans. Meanwhile, a flat fee would be regressive, foisting a bigger upfront cost on those who borrow smaller sums.

And what if lenders offer to pay the upfront fee on behalf of borrowers — is that illegal too?

Surely borrowers can just increase the size of the mortgage by the amount of the fee.

Around the world, commission structures tend to dominate, which lends some support to value.

In Britain, where brokers account for about 70 per cent of new loans written, upfront commissions to brokers from lenders are about 0.4 per cent — alongside a flat payment by the customer of a few hundred pounds.

In New Zealand and Canada, upfront commissions hover around 0.9 per cent and 1 per cent, respectively. The Irish central bank, with first-hand experience of a property crash, has stopped short of recommending ending commissions in a recent review of its mortgage market.

The only country that has banned them, The Netherlands, in 2013, has made upfront payments tax deductible, almost unthinkable here following the financial services royal commission. As a result of the ban, low-income earners are less likely to receive financial advice, according to a recent review by Fred de Jong. That’s no surprise when the flat fee is at least €2100 ($3300). “The main lesson to be learned from the Dutch commission ban is that it is not the answer to all problems caused by market failure, and that a ban also has downsides,” he says.

Here, Deloitte found about 60 per cent of mortgage broker users would have been willing to pay a fee upfront, and of that 22 per cent were only willing to pay up to $500.

The Dutch experiences suggests brokers are resilient. The total number of mortgage brokers in The Netherlands has fallen steadily from 9000 to 8000 between 2010 and 2015, the ban itself having little impact. And the share of broker-originated loans has only dropped a little, from 50 per cent to 45 per cent.

A better solution would be to mandate transparency. Customers should know how much the brokers are being paid by lenders, both upfront and later. That might prompt some thought about the value of the service and whether they might be able to negotiate a better rate with the bank directly.

“The standard variable rate bears little resemblance to the actual home loan interest rate offered, as the vast majority of consumers pay less than this rate,” the commission said. The confusion of borrowing, and perhaps the need for brokers, would ease considerably if lenders were compelled to reveal actual home loan rates from which an average or median could be calculated.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout