Monkeypox sparks Covid-19 ‘deja vu’ as CSL, Doherty Institute reveal pandemic lessons

An outbreak of monkeypox has created a barometer on how much the world has learned from Covid-19 and how to better fund biotech companies.

As Covid-19 infections soar, sparking the retreat of thousands of Australians from the office to working from home again, the World Health Organisation late on Thursday convened a special meeting to discuss a subject which global leaders thought they wouldn’t face for years.

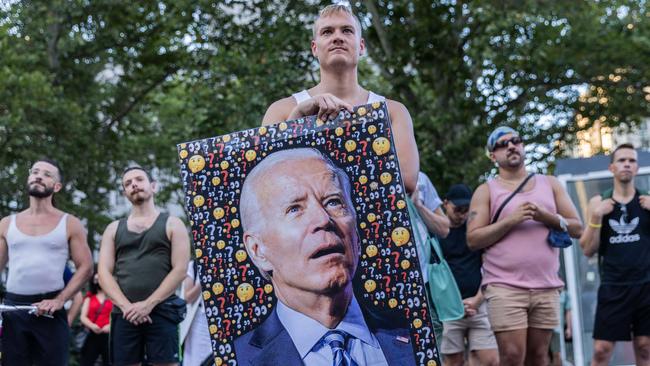

WHO met for the second time within weeks to consider whether to declare monkeypox a global crisis, sounding its highest-level alarm after global infections of the disfiguring virus, which is similar to smallpox, jumped from less than a handful in late May to more than 14,000 and climbing.

Countries are divided on the severity of the outbreak. But the response to the spread of the disease has created a barometer on how much the world has learnt in the past two-and-a-half years during the Covid-19 pandemic and whether it is better prepared to combat another health crisis.

One of Australia’s top Covid-19 and infectious disease researchers, Doherty Institute director Sharon Lewin, says while Australia has “responded well” to the monkeypox outbreak, the world’s biggest economy had experienced a sense of “deja vu”.

“The US has almost had a repeat of Covid. Testing wasn’t around, the CDC (Centre for Disease Control) were doing all the testing, people couldn’t get tests quick enough,” Professor Lewin said.

“There’s now about 3500 cases in the US and there’s not enough vaccines. It looks like a bit of deja vu unfortunately. It’s just that the whole world isn’t looking at monkeypox. So we’ve got to get better.”

The ability to respond to health threats quickly is vital to the global economy. Central banks across the world have been increasing interest rates to rein in the rapid return of inflation caused in part from the chaos the pandemic has sparked across supply chains, leading to soaring grocery prices and other essential goods.

Now — with the pandemic in its third year — cafes, retailers and other small businesses in Australian capital cities’ CBDs are under threat yet again, after the nation’s biggest companies urged their workers to work from home until the winter spike in Covid-19 infections subsides.

But predicting the pathogen behind the next health crisis is difficult. Before Covid-19, scientists were expecting the next pandemic to be a strain of influenza, following the swine flu outbreak in 2009.

And Australia’s biggest health company, CSL, is building a new cell-based influenza factory in Melbourne, replicating its research facility at Holly Springs in North Carolina that has been preparing for a future avian flu-driven pandemic.

The next health threat might be a completely different virus — such as monkeypox and even the outbreak of livestock foot and mouth disease in Indonesia — but the development of such facilities is not wasted as long as funding in the biotech sector is based on what Professor Lewin calls platform-based research, rather than specific projects.

Such platforms include mRNA vaccines — the technology behind Pfizer and Moderna’s Covid-19 jabs — that instruct the body’s cells to make a protein which can be modified to trigger an immune response for a range of viruses.

“Our funding system, at least in Australia, tends to put small groups in competition with each other. But if you had incentives to get large groups to collaborate, I think you can achieve a lot more,” Professor Lewin said.

“That’s what I’ve personally experienced in my career in science and it was really visible in the Covid-era, and those sort of behaviours scientists had can be changed by our funders; so I’m hoping that is one thing that will persist post Covid.”

While Covid-19 research has attracted billions of dollars from governments, investors and corporate philanthropy, there is still a reticence towards funding other biotech research.

Investing in biotechs is notoriously challenging, with even some of the biggest companies experiencing how success can quickly turn to failure; just look at CSL backing University of Queensland’s Covid-19 vaccine candidate, the trials of which were halted after its sparked false HIV positive results.

Amanda Gillon, senior partner at $200m fund BioScience, who has a PhD in molecular biology and biochemistry, said superannuation funds could play a greater role in biotech funding, given their long-term investment strategies.

Dr Gillon said the problem was many investors did not understand the value inflection points associated with biotech companies, which could lead them to feeling “burnt”.

“We do need that platform technology and you need a lot of money for that translation of research and development into commercial products. This requires long-term patient capital,” she said.

“The key point that is often missed — I mean everyone became an mRNA vaccine expert during Covid — is actually understanding where the value inflection points are and understanding that there is a risk attached to this, and it’s a risk that does diminish as you get further along that translation.”

Andrew Nash, chief scientific officer at CSL — which invests about $1bn in research and development each year — agrees, saying there “needs to be a really high-quality understanding of the risk and the science, and where the value lies”.

“There were small companies founded not that long ago that are now leading the global challenge with Covid, so there’s a real opportunity there,” Dr Nash said.

To this end, CSL has created Australia’s first “incubator” for biotech start-ups that will be housed in its new global headquarters being built in Elizabeth St, Melbourne as part of the city’s new biomedical precinct.

CSL will run the incubator in partnership with the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, and the University of Melbourne, after it secured funding from the Victorian government’s $2bn Breakthrough Victoria Fund.

“Formalising a place to nurture promising start-ups is a natural extension of our long-term support of and collaboration with many like-minded partners,” Dr Nash said.

“We hope to see significant long-term health, social and R&D benefits from this initiative, including greater retention and upskilling of domestic research and development capabilities and an increase in commercial acumen of precinct researchers.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout