United we stand: A golden opportunity for Leonora landholders

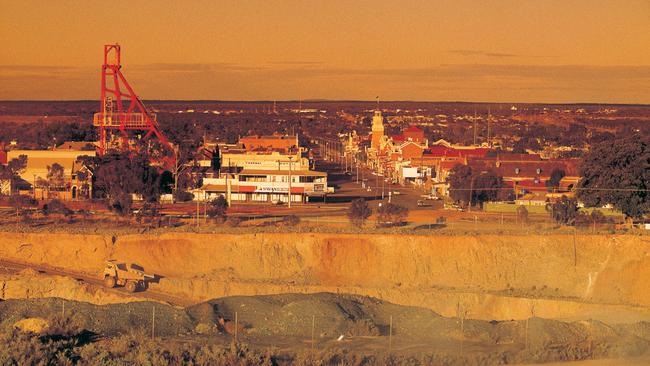

The mines and deposits that sit within 100km of Leonora could deliver a million ounces of gold or more a year if a way could be found to bring the major players together.

Behind the frenzy of speculation about who will lead the Leonora consolidation is one of Australia’s richest gold districts – and a prize that could be worth more than a million ounces of gold a year.

Kalgoorlie’s Super Pit is one of the industry’s most iconic, both for its size and its rich history. It is also a shining example of the value that can be delivered when tenements are consolidated.

Alan Bond’s decade-long quest to tie together the scattered leases that now make up the Super Pit remains arguably the most successful mining consolidation in the sector’s history. The Super Pit has now delivered more than 23 million ounces of gold, with a long life in front of it under the ownership of Northern Star Resources.

Bond’s work is 33 years gone, but a similar effort is now being attempted around Leonora, in an effort to turn the scattered mines of the district into a major gold hub under a single owner.

While Leonora won’t host a single site in the style of the Super Pit, St Barbara chief executive Craig Jetson says the mines and deposits that sit within 100km of Leonora could deliver a million ounces of gold or more a year if a way could be found to bring the major players together.

For the last six months the five major landholders in the district – St Barbara, Raleigh Finlayson’s Genesis Minerals, Red5, Kin Mining and Dacian Gold – have been engaged in a complex dance aimed at bringing together their scattered deposits – and gold processing plants.

So far only Dacian and Genesis have consummated any of those extended discussions.

While Jetson won’t be drawn on the status of any of those discussions, he tells The Australian that the extensive due diligence conducted by all of the companies had made the size of the eventual prize clear to all. “I‘ve got all the reserves and resources that I need for the next 30 to 50 years, but I can’t process it. Others have got very limited life of mine,” he says.

St Barbara’s 126-year-old Gwalia mine – once managed by Herbert Hoover before he became the US president in 1929 – is the jewel in the Leonora crown.

But, as it stands, Gwalia’s mill is capable of processing only 1.2 million tonnes of ore each year – it would take more than 85 years to process St Barbara’s current gold through the small plant.

Near neighbour Red5 has a 15-year mine life for its new 4.7 million tonne a year plant at its King of the Hills project, but that mill is also due for an expansion.

And Dacian’s problem has always been that its deposits can’t deliver enough ore to keep its three million tonne a year mill busy – a problem Genesis hopes to solve from its own deposits.

Kept fed, even in separate hands, the mills should be able to support gold production of about 600,000 ounces a year.

But Jetson says that a regional plan could see that total grow to at least 800,000 ounces a year, and a properly capitalised company would have the resources to build a plant capable of processing difficult-to-treat refractory ore, lifting the total by as much as half again.

“The missing link in all of this is the amount of refractory ore that’s in the region that is not being processed, because there’s no refractory milling capacity anywhere near the operations – and a standalone doesn’t work for most,” he says. The difficulty in processing refractory ore recently brought about the downfall of Wiluna Mining, and the only major plants with a proven track record in treating the ore in Western Australia are in Kalgoorlie.

St Barbara has refractory ore at its Aphrodite and Harbour Lights deposits, which Jetson says would deliver a business case for the company to build its own plant. But that still leaves plenty of regional refractory ore without a processing option, he says.

“If I look around me in the region, there are many deposits of refractory ore that are not standalone which would be available to grow the province even more,” he says. “There’s a lot (of refractory ore resources) not even declared because even though it’s been discovered, people know full well that they can never convert it – it’s very expensive and they don’t have the life of mine to convert mills for these satellite deposits.”

A single owner could also lead the relocation of the region’s rail line, Jetson says – a key factor that eventually forced the closure of some members of the previous generation of gold mines, including St Barbara’s Tower Hill and Harbour Lights deposits.

“Individually, the smaller stuff won’t work, but economies of scale and efficiencies with consolidation will work,” he says.

But, as the corporate dance continues, history also provides a warning note. In 1987, Bond paid Robert de Crespigny’s Poseidon $375m – $200m in cash and 214,000 ounces of future gold production and a $25m convertible note – to settle a major plank in the consolidation of the Super Pit.

While that transaction may look cheap at today’s prices, it highlights the dangers of running too hard and too fast. When the convertible note fell due, Bond couldn’t pay up and instead handed de Crespigny a controlling stake in General Mines of Kalgoorlie, effectively ensuring Bond’s exit from his own plan.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout