Turbine invasion raises anger levels in the NSW high country

Jim and Marilyn Williams have a view of the Snowy Mountains in all their glory. Soon they could also see a giant wind farm.

From their front gate, Jim and Marilyn Williams have a 360-degree view of the rolling Monaro countryside in all of its glory.

Soon they could also have a view of a proposed giant wind farm, courtesy of a proposal to clear land the size of 200 football fields to build wind turbines 1½ times the height of Sydney Harbour Bridge.

With close to $10 billion and 6500 megawatts worth of wind projects currently under construction, the dilemma being faced by the Williams family is being played out across the country.

Unlike coal, clean energy may be emissions-free but it is not without impact on the communities where the power plants are built.

Last week, a $1.5bn wind farm sprawled over 17,000ha in the Golden Plains Shire near Ballarat in Victoria was given state approval. The majority of that land is covered by farms and it is the site of the Meredith Music and Golden Plains festivals.

Likewise, the Crudine Ridge wind farm, between Mudgee and Bathurst in eastern NSW, has divided the community for years.

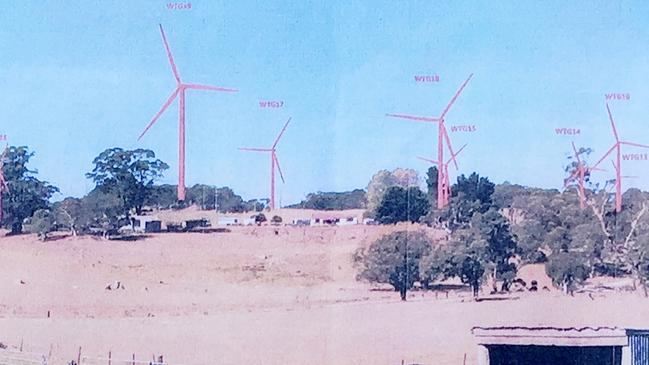

From their gate, Mr and Mrs Williams, a fifth-generation farming family that owns 1000ha in the hills, would be able to see 31 of the project’s 32 turbines.

“We don’t want those aliens coming in, putting up those monsters,” Mrs Williams said.

The turbines proposed for the Granite Hills Wind Farm near the Williamses’ property, 12km from Nimmitabel in southeast NSW, are each 200m tall. A new group of landowners — the Brown Mountain Residents Group — has been created to oppose the project, which threatens to spill into the broader Snowy Mountains region.

The project, a joint venture between Australian company Willy Willy and France’s Akuo Energy, would seek to chop down thousands of trees from Brown Mountain. “They called it Granite Hills because who’s ever heard of that?” Mrs Williams said. “If it was called Brown Mountain Wind Farm, more people would be angry. But that’s where it is.”

The $200 million project will generate 132 megawatts, enough to power an estimated 50,000 homes. Akuo Energy is currently writing a development application and environmental impact statement for the development, but has filed its Environmental Assessment Requirements.

“If approved, project construction is estimated to begin in 2020,” the project’s website says.

A spokeswoman for the project said it was a state-significant energy development — meaning it had a capital cost of more than $30m — and the companies involved would work hard to engage with the community.

David Williams, Jim Williams’s cousin, is the closest landowner to the turbines. From his property, he says, he will need to bend his neck backwards to see the top of the structure. “One is 780m away in a straight line but it’s on a hill 100m higher than the house,” he said.

One real estate agent told him the development would devalue his home by about 30 per cent.

Builder Kitt Bryce, chair of the Brown Mountain Residents Group, lives 2.3km from the closest turbine site. “I’m a firm believer there have to be better ways of getting energy,” Mr Bryce said.

“There’s been no consultation. They’ve said if there’s majority opposition to the project, they were going to go ahead anyway.”

Mr Bryce said the community was concerned about bushfires, as an enormous blaze destroyed several homes and burned through 18,000ha in nearby Bemboka in September.

Having 200m-tall wind turbines in bushland would, he said, stop waterbombing helicopters and aeroplanes from being able to get close to the fire. “There are so many environmental issues,” he said. “There so little I can do on my own block, and they can just go in and clear 500 acres.”

Libby and Jim Litchfield live near Cooma, also in the Snowy region, and own Hazeldean, one of Australia’s oldest and most prestigious merino stud farms. They said locals had been battling major renewable projects for many years, angry about the willingness of companies to compromise the land’s natural beauty.

“It’s ruining the pristine landscape,” Ms Litchfield said. Mr Litchfield added: “There are very few parts where you can go to the countryside and actually get uninterrupted views. That’s gone now.”

Will Jardine owns the Nimmitabel Bakery. He said the state government should step in and block the project, which, he said, would not deliver the jobs it has promised.

“When people move to Nimmitabel, they’re looking for a tree change; they move to the eastern side of town,” he said. “That area would be forever devalued.”

A spokeswoman for the Granite Hills Wind Farm said a large area around the site had already been cleared, and the company would keep speaking to locals. She did not say whether the project would be withdrawn if the community called for it.

“The site is mostly cleared and grazed which allows Granite Hills to minimise distribution of native vegetation and habitats,” she said.

“We have met with nearby stakeholders and are currently undertaking another substantial round of neighbour visits. Regular engagement with the community will continue in 2019.”

The NSW Department of Planning and Environment said it was reviewing the proposal and assessed all projects on merit.

A spokeswoman for the Clean Energy Regulator said power stations like Granite Hills would be able to claim Large-scale Generation Certificates under the Renewable Energy Target until 2030. Figures from the Clean Energy Council show there are projects worth $9.53bn that will generate 6561MW and create 5030 jobs under construction nationwide.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout