Technological revolution to power miners in shift from fossil fuels

Some of the nation’s biggest miners are banding together to rapidly accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels in the resources industry.

Giant batteries made of bricks, electric jumbos and underground mines that don’t need ventilation are just some of the technological revolutions on offer as a group of major Australian mining companies put their heads together to plot a major revolution in the way mining is done and help wean Australian mines off diesel and other fossil fuels forever.

In an unusual step, mining majors South32, OZ Minerals, IGO and a suite of contractors and equipment manufacturers have formed a consortium to share information in the hope it will help them match the big technology budgets of mining giants such as BHP and Rio, working together to plot the full electrification of major Australian mines.

The Electric Mine Consortium, to be formally launched today, brings together miners and equipment manufacturers including Sandvik and Epiroc, as well as major mining contractor Barminco, software giant Dassault, utility Horizon Energy, engineers Hahn Electrical, renewable energy company Energy Vault and new economy start-ups Safescape and 3ME Technologies.

By working closely together and sharing information as they work to electrify their own operations, the group hopes to rapidly accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels in the mining industry, it says.

According to a recent survey of global mining executives undertaken by research group State of Play, 87 per cent believe that all existing mine sites will become fully electric within 20 years and 60 per cent believe the next generation of greenfield mines will be fully electric.

OZ Minerals boss Andrew Cole said this month the company was already trialling fully electric drilling rigs and other equipment on its South Australian copper mines, and South32 chief technical officer Vanessa Torres told The Australian the electric revolution was coming quickly.

South32 is currently planning the design of a major new mining project in Arizona, and Ms Torres said the company was already looking to keep the mine as free of diesel and fossil fuel as possible.

“Our aspirational goal is not to have diesel out there and largely use an electrical fleet underground, as well as at the surface for concentrate transport and things like that,” she said.

For new mines, the potential savings are enormous. Particles emitted by diesel engine exhausts are one of the biggest safety concerns in underground mines, and the ventilation required to keep workers safe is one of an underground mine’s major costs.

Hermosa might be built too soon to take full advantage of the technology’s full potential, Ms Torres said, but South32’s involvement in the consortium would allow the company to plan for the future.

“What we are doing is that we engage directly with suppliers, and we are using in our mine design not only the current equipment but the equipment they are developing,” she said.

“So working with them closely, we can have some insights. I think the other thing is how you design for optionality. So for instance, if you think about ventilation on demand, you want to be able to have ventilation systems where you can reduce it if you’re able to.”

State of Play co-founder Graeme Stanway said industry estimates suggested that the full electrification of mines could save 30 to 50 of current energy costs, cut maintenance bills by as much as 25 per cent, and slash the cost of ventilating underground mines by 40 per cent — as well as almost completely eliminating their direct carbon emissions.

Mr Stanhope said end users of minerals were also becoming increasingly concerned about the carbon footprint of their suppliers, particularly in Europe, potentially giving electrified miners a marketing advantage over their diesel-powered peers.

“I’ve been surprised this year about just how aggressive the market competition is between battery mineral suppliers. You may find a lot of the battery mineral suppliers will have to really move very fast, if others have, because it will be like the juxtaposition with coal and other energy sources — it could get quite aggressive on the marketing front.”

But savings for miners may translate into a seismic shift in the business model of the equipment manufacturers that supply them. While mining trucks and drilling rigs can come with an up-front cost in the millions, the initial price-tag is dwarfed by the value of contracts for spare parts and maintenance.

But electric engines come with far fewer moving parts and, aside from the cost of replacement batteries, far lower maintenance bills, and manufacturers such as Sandvik are using their role in the consortium to ponder their future business model, according to Sandvik Australia executive Andrew Dawson.

“In an electric vehicle, particularly a heavy battery electric vehicle like a large truck or a large loader, there’s less moving parts. So there’s no engine, no transmission, no PTO or torque converter. So there’s less things moving, less things breaking,” he said.

Mr Dawson said mine electrification threw up new business opportunities for equipment makers, such as the supply of vehicle batteries as a service — including not just replacement batteries, but charging points and associated infrastructure, as well as use of the same batteries at other parts of the mine, not just in vehicles.

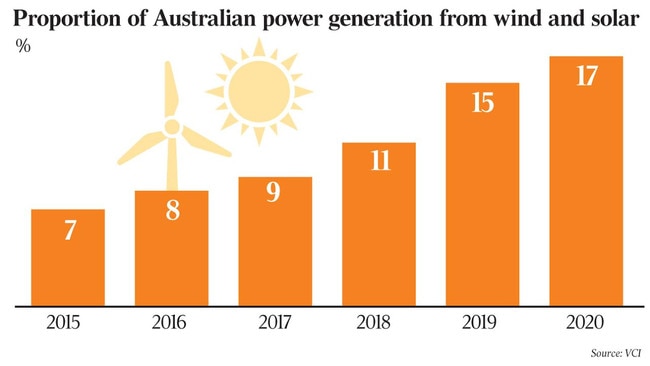

The full electrification of the industry ultimately depends on battery technology. Wind and solar are cheap and plentiful in Australia, but modern mines run 24 hours a day, irrespective of whether the sun shines or the wind blows.

Storing that abundant renewable energy for future use will be the key for any company considering the switch, and perhaps the most striking technology on offer within the consortium is Energy Vault’s giant brick-based battery.

At heart it is a 30 storey tower that stores energy by using renewable power to lift 35 tonne bricks to the top of the stack when wind and solar are plentiful, and releases it by using the weight of the bricks to spin generators when it needs to be released.

Energy Vault has already used a $US110m ($142m) cash injection from Softbank Vision Fund to build a full scale operating plant in Switzerland, connected to the Swiss grid in July 2020, and have identified Australia’s remote mining sites as a key potential market for the technology.

Chief executive Robert Piconi told the Australian the technology was simple in concept but run by sophisticated software, and had the potential to store energy for long periods of time — a 35 tonne brick, once lifted into place, simply sits as a reserve of stored energy until it is needed.

A modular system, capable of delivering 20 megawatts of power over an eight hour period, would take up about three acres of land, he said, and the giant bricks would be built on site, using whatever materials were to hand — including, potentially, tailings wastes that would otherwise sit in an on-site dam.

“With mining, what’s very interesting for us is we can utilise the waste of materials, the tailings, so we can actually save the mining companies the cost,” he said. “Part of the reason that renewables haven’t been deployed is that storage is so expensive. And now solar and wind, you can deploy for less than two cents a kilowatt hour. So it’s super cheap. But there haven’t been storage solutions that have been economical, and ones that are safe and environmentally friendly.”

By working together the consortium says it hopes to accelerate the electrification of their own mine sites and supply chains — proving up the technology and commercial case for electrified mines in the expectation that where they lead, smaller miners will rapidly follow.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout