Super funds seek energy policy action

Australia’s powerful industry super funds have savaged the nation’s dysfunctional electricity market.

Australia’s powerful industry super funds have savaged the nation’s dysfunctional electricity market, calling for governments to intervene and create special investment vehicles along with multi-decade supply contracts to entice long-term funding from investors.

The group — representing the nation’s biggest industry players with $678 billion in funds under management — said the lack of a settled energy policy and continued absence of a carbon price risks leaving Australia with the wrong generation mix, inadequate infrastructure and the wrong investment signals for its members.

“The lack of a genuine long-term technology-neutral energy policy is a major factor undermining fund investment,” Industry Super Australia says in a discussion paper.

Australia’s industry super funds hold $40bn in energy sector commitments globally, but the scale of electricity investment required by 2050 is measured at an $888bn split between generation, transmission and distribution, according to modelling included in the Finkel Review.

“In the normal course, portfolio investors would be lining up to fund long-term solutions in this changing industry for Australia,” the report says.

“But so far, the silence from investors is deafening. This is no surprise given the uncertainties around climate policy and related environmental, social and governance risks. Without consistent policy settings, this situation is unlikely to change.”

The group — whose members including AustralianSuper and Cbus — warns that a radical rethink of the sector is needed to spur portfolio investors to fund long-term solutions for the industry.

“Clearly, we need a complete overhaul of policy before large swathes of heavy industry goes offshore,” it says. “If that happens, governments will then face huge economic and social adjustment burdens as whole industries need to transition to new workplaces in new regions.”

The Coalition is largely focused on solving immediate issues in the grid such as cutting household power bills and boosting security of supply, partly by re-regulating the sector and applying pressure on the big power players to comply with its interventionist demands.

However, the nation’s industry super giants argue that the investment focus needs to switch from short-term speculation to working with governments to determine the long-term spending needed to modernise the grid.

Governments may have to wade into the market and work with big investors on nation-building projects to ensure the right generation mix is in place with special investment vehicles an option.

“The government may find it advantageous to construct investment vehicles that minimise downside risks and encourage long-term equity partners. In this regard, some changes may need to be made to the financial and taxation structure,” the paper says.

“Other forms of involvement may also be required depending on the objective. Government may also consider direct involvement and co-investment options with superannuation funds for special projects.”

Scott Morrison has already shown a willingness to use taxpayer funds to invest in the power market, chiefly through Snowy 2.0 but also via the government’s plan to underwrite generation.

Industry Super also calls for creating competition for the long-term supply of capacity and electricity at set emissions targets via contracts of 20 years or longer, in a bid to move away from the volatile spot market for power pricing. Super funds would be given incentives to fund the necessary investment.

“Rather than fixating on the spot market for energy pricing, the national electricity market should be focused on creating a competition for the long-term supply of capacity and energy at given emissions targets. This can be achieved by ‘auctions’ of longer-term contracts of 20 years duration or longer,” the report says.

“On the demand side, contracts would be purchased by state governments, but also private sector agents, motivated at securing reliability of supply and price. On the supply side, long-term asset equity owners in infrastructures appreciate the certainty of guaranteed rates of return on their investments.”

A public energy planning body could also be created to make decisions in the national interest and invest in network maintenance and expansion as the grid transitioned to cleaner forms of energy.

“To do its important job well, the energy planning agency would need to have deep professional capacities, and insulation from the day-to-day vicissitudes of partisan politics. The Australian Energy Market Operator could be strengthened to perform this planning role.”

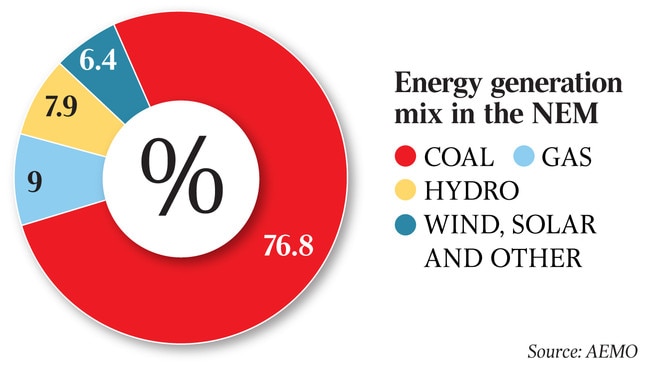

The industry body also calls for nuclear to be part of Australia’s power mix given uncertainties about the switch from a coal-dominated grid to renewables.

“Investors looking for longer-term solutions such as possible clean-coal technologies or gas-fired baseload and especially small or large-scale nuclear would be placed in an extremely risky position,” it says.

“Right now, it seems the only politically acceptable investments appear to be relatively small-scale, quickly deployed renewable wind or solar projects. It is far from certain that is a complete solution or puts us on the optimal trajectory.”