Shipping industry fuel reforms to hit local miners

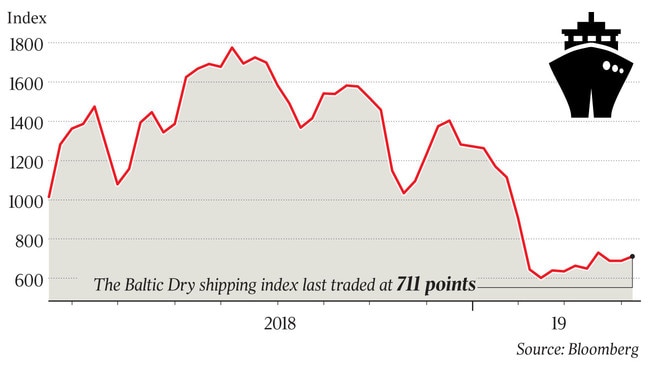

Miners are bracing for higher costs thanks to tough new environmental measures in the global maritime industry.

Australia’s mining heavyweights are bracing for higher shipping and fuel costs ahead of the looming introduction of tough new environmental measures in the global maritime industry.

The world is now just 38 weeks away from the formal start of the International Maritime Organisation’s new requirement of a 0.5 per cent cap on the sulphur content of all marine fuels, down from 3.5 per cent today.

The policy effectively ends the burning of the high-sulphur fuel in its current form, forcing shipping companies to source more expensive, cleaner fuels or fit scrubbers that can capture the sulphur emissions from their vessels.

Analysis from Macquarie Wealth Management earlier this year estimated that the changes will add about 30 per cent to shipping costs, which will have knock-on effects for commodity markets and consumers.

And Wood Mackenzie analyst Rudi Vann warned that the changes are also likely to increase the cost of diesel fuel — one of the mining industry’s single biggest costs — by 6-7 per cent.

Australian iron ore miners BHP, Rio Tinto and Fortescue Metals, which between them ship almost 800 million tonnes of iron ore from Australia to Asia, are set to be among the hardest hit by the new rules.

Rio Tinto chief executive JS Jacques told The Australian that the scale of the miner’s shipping needs meant it would need to explore multiple alternatives.

“We are looking at all options at this point in time,” he said.

“We are one of the largest users of ships so we will have to use all the levers to make sure we are fully compliant with those regulations.”

The installation of scrubbers shaped as one of the key means of meeting the new standards, although that has been complicated by a lack of industry capacity to install all the scrubbers required, as well as debate about the environmental merits of the process.

Singapore and China have already moved to restrict the use of some scrubbers in their ports.

Switching to very low sulphur fuels is a simpler, albeit expensive, move but there are concerns about the ability of supply to keep up with demand. Fortescue chief executive Elizabeth Gaines said the company’s shipping team was very involved in preparing for the new requirements, identifying the availability of low-sulphur fuels as a key focus.

“There’re still some grey areas around the fuel refiners and what fuel they will produce and what will be available, so it’s still a work in progress,” she told The Australian.

“I wouldn’t say that everything has been done to understand the impact it may have because I think there are still other industry responses that are required before everyone will have a firm understanding. But rest assured we are very proactive in our participation as this develops.”

According Wood Mackenzie’s Mr Vann, total demand for all types of low sulphur marine fuel in Asia Pacific is expected to reach 1.9 million barrels per day once the new rules kick in.

In contrast, the supply of very low sulphur marine fuel in the region will only reach 0.3 million barrel per day and it will take time for refining infrastructure to catch up.

“The issue particularly in Asia is the supply is far outstripped by the demand for this sort of fuel and there are very limited options to export that from other markets,” Mr Vann said. “There’s going to be a shortage there, so people are also going to have to utilise marine gas oil as well as a substitute for high sulphur fuel oil. That’s going to be more costly, and either way it’s going to increase the operating costs.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout