Pink diamond mines aren’t forever

But Rio Tinto sees a future in tourism once mining ends at the Argyle site.

The closure of Rio Tinto’s Argyle diamond mine next year will end a remarkable chapter in Australia’s mining history, but it might not be the end of the Argyle story.

Rio Tinto’s copper and diamonds chief Artaud Soirat yesterday revealed the company had been approached by a number of parties interested in converting Argyle’s mine camp into a tourist resort, a move that would ensure the Argyle name lives on well after the final gems are recovered from the mine.

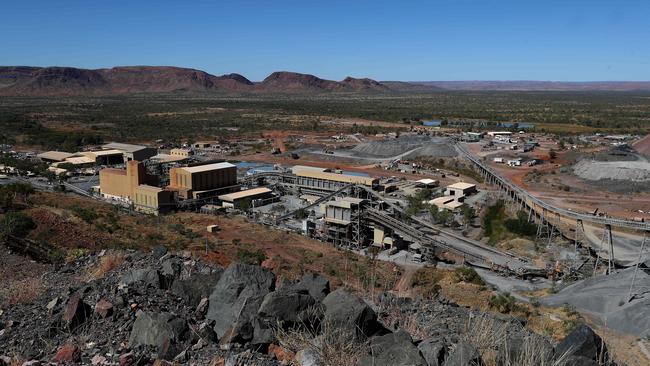

Converting the mine camp may not be as fanciful as it sounds. The accommodation is built on a hill with spectacular views across the Kimberley landscape with its baobab trees and termite mounds. While the camp’s buildings reflect Argyle’s 1980s origins, its easy to see how, with its swimming pool and water features and with kangaroos wandering around the grounds, it could be converted into a tourist destination.

Mr Soirat said the site had tourism potential.

“It is a really beautiful environment, there is an airport, and there is a good camp,” he said.

“There would be people who want to do something with this.”

The tourism option is one factor being studied by Rio Tinto as it moves towards the end of mining at Argyle.

The company is working closely with state government regulators as it weighs up just how to rehabilitate the mine’s open pit, tailings dam and processing plant while also leaving a positive legacy for the region and its people.

Argyle’s 450-strong workforce is also front of mind.

Many of the workers are being absorbed into Rio’s massive iron ore division, while the experience in block caving at Argyle — a relatively new but increasingly important mining technique — means others may find work at block cave projects overseas.

Rio has also launched a program called Life After Argyle, where it is funding courses for employees planning on making a move into other industries and careers once the mine closes.

Argyle has long been an anachronism inside Rio Tinto. The mine’s profits are minuscule compared to the money-making machine that is the company’s Pilbara iron ore operations, and its consumer-focused end market is unlike anything else inside the mining giant.

Rio has sold off billions of dollars worth of non-core assets in recent years but Argyle has remained, and chief executive JS Jacques has repeatedly — and surprisingly — expressed his desire to see diamonds remain within the Rio portfolio.

Rio also owns the Diavik mine in Canada’s far north, and the company is exploring for more diamond deposits in Canada through its joint venture with Star Diamonds. Mr Soirat said that while the diamonds business was relatively small, it was very profitable — making it emblematic of the “value over volume” mantra that has defined Mr Jacques’ time at the helm of the company.

“It’s not a big business in Rio Tinto. However, it’s a very profitable business,” Mr Soirat said.

Argyle has been a valuable testing ground for block caving, allowing Rio to hone those techniques on a smaller operation.

Block caving involves tunnelling deep beneath an orebody and establishing a series of chambers, into which the orebody gradually collapses in on itself.

In the case of Argyle, a network of 30km of tunnels were established before the underground mine could start production.

The technique involves high upfront costs but comparatively low ongoing operating costs, which makes it suitable for large-scale, long-life projects such as Rio Tinto’s massive Oyu Tolgoi copper mine in Mongolia and its proposed Resolution copper mine in Arizona.

“There are things that we are developing and experimenting on here that are being transferred to Oyu Tolgoi. In some ways it may be more suitable to test new ideas on a smaller mine than it would be to do it at Oyu Tolgoi,” Mr Soirat said.

“That’s why we want to stay in the diamond business.”

The closure of Argyle next year will be met with a mixture of sadness and nostalgia. Its discovery 40 years ago turned geological thinking about the nature of diamond deposits on its head, and it has remained the sole major diamond mine in Australia.

Rio also took a different approach to Argyle when it built the mine in the mid 1980s.

Joanne Farrell, Rio Tinto’s soon-to-retire group executive for health, safety and the environment, spent three years working at Argyle during the mine’s early days and recalled this week how the company set a target of 20 per cent female employment — a multiple of the rate elsewhere in the mining industry at that time.

The company also wanted 70 per cent of the workforce to be “cleanskins” who had never worked in the mining industry before, as it set out to establish an alternative culture to the combative and combustible workplace environments that marred the mining industry at that time.

Argyle was also the catalyst for the breakdown of De Beers’ near-monopoly over the global diamond supply when it broke away from the diamond cartel in the mid 1990s.

It was a bold move that looked to be a crazy one when De Beers retaliated by dumping more than a year’s supply of pink diamonds on to the market, but Rio weathered the storm and the Argyle brand is recognised today among diamond aficionados globally.

Those workers responsible for guiding Argyle through its final days recognise its special place in Australia’s mining history.

“In 10 or 20 years’ time, we know we will be able to look back with pride and say ‘we worked at Argyle’,” the mine’s operations manager Brendan Murphy said.

“There’s really nowhere else like it in Australia.”

The reporter travelled to Argyle as a guest of Rio Tinto

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout