Nickel Mines: How Norm Seckold used a ban to turn fortunes around

Norm Seckold’s Nickel Mines got nearly burnt by an Indonesian ban. Now the miner is looking at a potential IPO.

When Indonesia slapped a ban on the export of unprocessed nickel ores at the start of 2014, it should have been a disaster for mining veteran Norm Seckold and his new Nickel Mines venture. Instead, it triggered a series of events that Seckold believes has put Nickel Mines on a path to potentially become the biggest pure-play nickel producer in the world.

Seckold, best known to Australian investors for building Bolnisi Gold into a company that was eventually taken over for just under $1 billion, is now leading Nickel Mines towards a potential IPO that would be among the biggest new mining listings in Australia for several years.

While a formal decision has not yet been made, any IPO would raise around $125 million and would value Nickel Mines at around $400m.

A successful IPO would represent a big turnaround from 2014, when the Indonesian ban forced Nickel Mines to immediately halt the export of nickel laterite ore from its big Hengjaya mine on the island of Sulawesi. The mine had only been in operation for a few months at that stage, and the ban meant it looked like Seckold and Nickel Mines had all but torched the $15m or so they’d spent brining Hengjaya on line.

“It was an unpleasant experience because we had committed this capital to get this thing going and then the revenue was cut off,” Seckold says.

But the ban had the desired effect of inspiring a massive investment in downstream nickel processing. Tsingshan Holdings — a large private Chinese company with a long history of buying unprocessed nickel ore from Indonesia — reacted by pumping billions into building a big new Morowali nickel and stainless steel processing park from scratch in Sulawesi, just down the road from Hengjaya.

The industrial park is staggering in its scale: it has its own 1.26GW coal-fired power station that is big enough to supply all of Brisbane, a full-size port, a dedicated hotel resort and employs 18,000 workers.

“While we weren’t super happy about the ban, it was absolutely the right thing for the country to do because the Tsingshan group turned around and invested $US5bn in this industrial park that is now producing 150,000 tonnes of nickel a year and which is still growing,” Seckold says.

Now Nickel Mines has a massive industrial facility right on its doorstep, and has struck a deal with Tsingshan which will see Nickel Mines enter the far more lucrative world of nickel processing.

While the world of nickel laterites and nickel pig iron in which Seckold is now playing has long been considered as the ugly sister of the nickel industry, Seckold believes his company has got the right orebody and — more importantly — the right partner to start changing that perception.

Tsingshan is considered one of the global leaders in so-called Rotary Kiln Electric Furnace processing, a comparatively low-capex method of processing nickel laterites, and has so far built 20 RKEF lines at its Morowali industrial park to date that process laterite ores brought to it from across the archipelago.

Tsingshan — which owns a 20 per cent stake in Nickel Mines — is now building another two RKEF lines at Morwali for Nickel Mines, which has an agreement to buy a 70 per cent interest in the lines for $US70m. Nickel Mines also has an option to go to 100 per cent ownership of the lines — which will together produce around 16,500 tonnes a year of nickel — by paying $US120m within 12 months of first production from the lines.

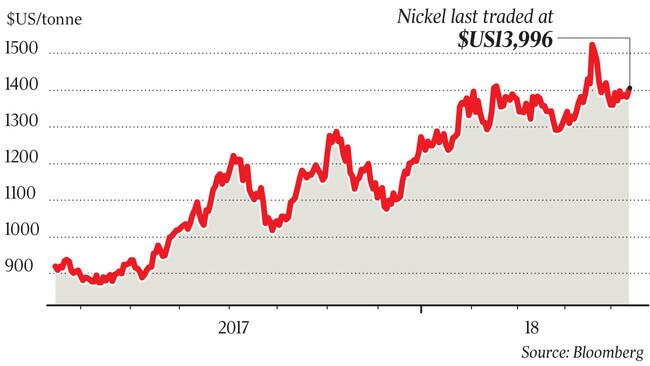

That translates into a cost of around $US14,500 a tonne of annual production capacity, which is just a fraction of the cost of other big nickel laterite plants built around the world. It is shaping as a potentially lucrative venture.

An analysis by consultancy Wood Mackenzie found Nickel Mines had lowest incentive price of 41 undeveloped and unfunded nickel projects around the world. At a nickel price of $US16,000 a tonne the project has an internal rate of return of 36 per cent, while at $US22,000/t the post-tax IRR jumps to around 59 per cent.

Seckold believes Nickel Mines could potentially double its output again, given the prospect of adding another two RKEF lines.

The current resource at Hengjaya of 57.7 million tonnes at 1.81 per cent nickel can support a 30-plus mine life, but Seckold notes only around half of the outcrop at the project has been drilled to date. “We will be a member of a very small group of listed companies that are pure nickel plays,” Seckold said.

“There’s nothing inked, but I would like to think that we could participate in the further expansion of the industrial park and get ourselves to the point where we are the largest pure nickel play in the world.”

Bell Potter is acting as lead arranger on the potential IPO, while Nickel Mines has signed up Blackpeak Capital as its adviser.