How Thai-owned Centennial Coal burnt Origin and fuelled Australia’s energy crisis

In 2022, Centennial Coal sold shipments of coal to international buyers rather than meeting supply agreements for the Eraring power station, triggering upheaval in Australia’s energy market.

The decision by a major NSW miner to redirect coal to lucrative overseas markets rather than supply Australia’s largest power station in part triggered the winter energy crisis that paralysed the nation’s electricity grid in 2022, sources have revealed. Centennial Coal, owned by listed Thai company Banpu, in 2022 quietly sold shipments of coal to international buyers rather than meeting agreements to supply the Eraring facility.

It was a decision that caused significant losses for Origin Energy, fuelling the country’s energy market crisis.

The move was not illegal, and it is believed Centennial paid compensation in line with its contract. However, it became a major driver of Origin’s earnings slump, exacerbating upheaval in Australia’s energy market that eventually saw households stung with price increases of up to 25 per cent.

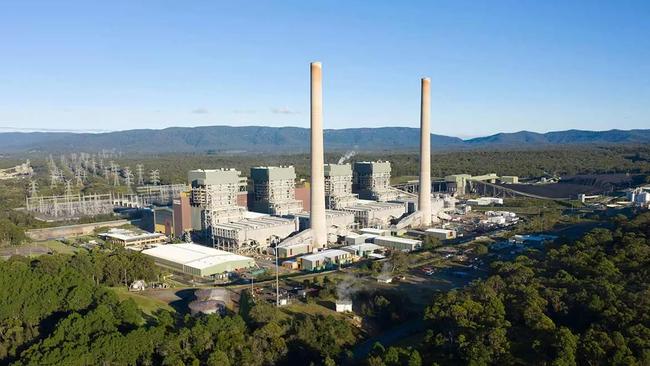

Origin’s Eraring coal power station supplies a quarter of NSW’s electricity, a critical source in 2022 when Australia was trying to avoid the energy chaos that was gripping Europe following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Russia was then the dominant supplier of gas to Europe. Because of sanctions, Europe was scrambling to source alternative fuel supplies. The global energy crunch sent household bills soaring, with a spate of retailers collapsing.

Australia, a major exporter of gas and coal, was largely sheltered from the chaos.

However, this quickly changed by mid-2022 when a spate of unplanned coal outages coincided with the onset of a La Nina weather event that brought heavy rain, disrupting coal mining operations along the east coast.

In June 2022 Origin announced its Eraring coal power station was running low on coal. Australia’s energy market quickly unravelled.

Origin did not publicly disclose why it was running low on coal, alluding instead to heavy rain. But sources briefed on the situation told The Australian that Origin’s supply issues were caused by Centennial opting to sell shipments via the export market.

“Coal loaded on the conveyor that would have normally gone to Eraring was instead exported out of Newcastle,” one government official briefed on the situation told The Australian.

A spokeswoman for Origin declined to comment. Centennial said the allegations were incorrect but declined to specify which elements the company denied.

“The contractual arrangements between Centennial and Origin are subject to confidentiality provisions and accordingly we are not permitted to provide you with any information regarding those arrangements,” Centennial’s executive general counsel and company secretary Melinda Loh said.

With electricity supplies from Eraring desperately needed, the facility quickly ran through its normally ample reserves. Eraring had capacity for more than 1.5 million tonnes, which were then supplied from Centennial Coal.

The Australian understands that Origin struggled to buy alternative supplies as wet weather disrupted train services and coal operations, particularly in Queensland and NSW.

To remove the logjam, the NSW government prioritised freight trains to Eraring at the urging of Origin, sources told The Australian.

In the months since, Origin steadily lowered the amount of coal it purchased from Centennial. Under the terms of the supply agreement struck between the pair, Centennial would have been liable to pay compensation, sources familiar with other contracts of the company said.

But in 2022, as the world scrambled for new energy sources, coal exported from Australia was trading in excess of $400 a tonne – far beyond what Origin would have received.

To compound the woes, the loss of Eraring’s capacity meant Origin was also forced to buy electricity from Australia’s wholesale market to meet demand from its four million customers. But the wholesale electricity price at that time surged after the loss of Eraring and a spate of other unplanned outages, meaning Origin was forced to buy replacement capacity at elevated levels.

With some of Australia’s largest coal power stations out of action, Australia’s national electricity market was suddenly short of capacity, and generators turned to gas to ensure price stability.

Gas is typically used as a peaker – with power stations turned on only during times when demand is high or supplies of electricity from coal or renewables are running low. This typically meant gas power stations might run for a few days before being idled when traditional baseload generators are restored.

But with coal capacity significantly reduced, gas was running round the clock – which saw a rapid depletion of stockpiles from Victoria, the state most reliant on the fuel source during winter.

The rapid depletion of stockpiles saw the Australian Energy Market Operator plead with companies to avoid buying gas from Victoria for electricity generation outside of the state. One former industry executive said this meant numerous gas power plants were forced to run on diesel. “There were diesel trucks lined up and down the road and the plant ran on oil, which was the only way we kept the lights on, but did very little for emissions,” said one industry source familiar with the workings of Snowy Hydro.

Stockpiles of gas were running so low that prices surged – triggering a rarely used price cap for both gas and electricity.

However, these caps, which had been set under market rules developed earlier, were too low, as the generators would have made heavy losses if they dispatched at those levels.

As a result, there were widespread warnings of blackouts along Australia’s east coast, which forced the Australian Energy Market Operator to suspend the wholesale market.

For a week AEMO was forced to manually order specific generators to go online as the functioning of the market collapsed.

The chaos saw Australian wholesale electricity and gas prices surge, with little respite until later in the year, which caused significant increases to annual bill tariffs, known as the default market offer.

The default market offer is calculated annually as the Australian Energy Regulator considers the wholesale cost of electricity, and the costs of transmitting electricity and complying with government rules and regulations. Wholesale energy costs incurred by retailers are the largest component of the calculations.

“This chaos was what sowed the seeds for the price shocks that people felt in 2023,” said one industry executive.

In the midst of the chaos, as Origin announced a series of profit downgrades, the share price of Australia’s largest electricity generator was languishing at around $5.50 share – about 45 per cent below what it had been trading at 2020.

For Brookfield – the Canadian private equity giant – it was an opportunity.

Still smarting from its failed bid for AGL Energy alongside billionaire Mike Cannon-Brookes, Brookfield was still keen on Australia as the destination for billions of dollars in investment to accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels.

In August, Brookfield and its partner EIG Partners lobbed their first bid of $7.95 a share, though it quickly rose to $8.81 – a handsome rise from where shares had recently been trading.

The deal appeared certain to progress if the pair could allay competition concerns. Brookfield’s offer to invest $20bn to accelerate the energy transition appealed to the federal government, which was keen to have renewables provide 82 per cent of the country’s power by 2030.

Governments were desperately trying to avert a cost of living crisis. Annual electricity tariffs were being recalculated, and industry figures were insisting bill increases of more than 35 per cent were on the cards – whereas the government had pledged to cut electricity bills by $275 a year.

As the federal Labor government mulled intervention, the NSW Coalition government mulled increasing coal royalties that it could then redistribute to households, a source said. A rebate on household bills was the favoured intervention in Europe, but eventually a cap on the price of coal and gas was introduced.

The intervention caused a firestorm of criticism from coal and gas producers, but for Origin it was a boon.

Coal, which had recently traded above $400 a tonne, was suddenly capped at $120 a tonne. This was lower than Origin was paying for its coal at Eraring before 2022, and it was quickly able to replenish supplies at discounted rates in exchange for guarantees to increase electricity generation that in turn helped lower wholesale electricity prices.

Eraring, which had been losing money, was suddenly profitable.

International gas prices remained high, so Origin’s LNG business in Queensland boomed.

Shares in Origin rose as a result, pilling pressure on Brookfield and EIG to lift its offer. A revised offer did eventually come in at $9.43 a share.

Brookfield and EIG failed to sway enough shareholders.

“We knew Origin would recover its earnings but the intervention meant that recovery came a year before Brookfield had anticipated, there isn’t much else the consortium could have done,” said one banking executive.

“The irony is that the government wanted this deal.”

In September this year, Centennial said it would cut 200 jobs after failing to win a new supply contract with Origin. It blamed the state coal caps and high costs. Origin decided not to renew a deal beyond the end of 2024.

Centennial will instead pivot to shipping its thermal coal for the export market, potentially a profit driver should international prices remain high.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout