Dead sheep, locked gates, police complaints in high-voltage battle over transmission towers

Farmers along a new ‘energy superhighway’ say they have been thrust into a world of pain as Victorian landholders vow to lock their gates.

NSW farmer James Petersen has had many low points in his dealings with the transmission giant pushing high-voltage powerlines through his property.

The shonky fencing bisecting his sheep paddocks, the dead ewes, the disruption to his work, the hours lost to endless phone calls sorting out misunderstandings between contractors, subcontractors and sub-subcontractors … he didn’t think things could get much worse. Then one day Petersen, 34, arrived home to find police at his door. This was a new low.

“It’s definitely worrying having police at your house,” he says. “I asked them what they were investigating and the police officer said criminal trespass, against me! I’m not sure how that works when we own the property.”

This complaint relating to the transmission easement on his property came to nothing but, like the security guards who turned up another day, it felt heavy-handed and, yes, intimidating for a young farmer with crops to harvest and livestock to grow.

“I think the intent of that call to police was to try to scare James,’’ his lawyer Lochie Gittoes says. “Everyone’s aware that he owns the land and can’t trespass on it.’’

It’s a bright summer’s day at Petersen’s property outside Uranquinty, officially known as “the friendly village”, southwest of Wagga Wagga.

On the approach, the silvery glint of Transgrid’s half-built transmission towers catch the eye. Soon about 12 of these 65-metre tall structures will march across Petersen’s paddocks and he can’t stop them.

Further west, farmers Richard and Sally Carn look up at the line of newly completed towers – the closest about 400 metres from their home – that stretch to the horizon like an advancing army of steel giants. Like Petersen, they pour their lives into their farm and they’re still scarred by this unwelcome intrusion.

“We’ve been through drought and that’s hard but it’s not like the mental stress of dealing with this,” Richard says. “We understand it needs to be built but the way we have been disregarded and treated has made it worse. We didn’t ask for any of this.’’

Locals tell of a teenage son of a farmer being threatened by a contractor trying to get on to the property, of biosecurity plans being ignored and agreements flouted.

Anthony Cummins has four half-constructed towers on his property and describes it as a “cowboy show where nobody is answerable”. He’s had hundreds of sheep escape onto the road, cows and calves accidentally separated in a revolving circus of open gates and has caught contractors driving around his property, well off the easement. He’s sick of picking up plastic bags that pose a hazard to his cattle and wonders where those damned new weeds came from.

“They locked me off my own property another time, locked my gate with a different lock,’’ he says in disbelief. “It’s the most unprofessional building schedule I have ever seen.”

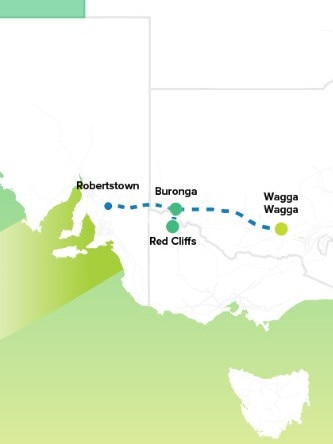

This is one small part of the $2.3bn Project EnergyConnect, Australia’s largest transmission project involving a new 900km high-voltage line running from Robertstown in South Australia’s mid north to Wagga Wagga in the NSW Riverina, with a connection to Red Cliffs in Victoria.

It is the most advanced project in the mammoth endeavour to build 10,000km of new poles and wires to connect the flood of solar and wind generation to the grid.

Petersen, the Carns and their neighbours are the guinea pigs in testing how this transmission construction will play out as anxious landholders along other routes managed by different companies watch on.

Will it be a respectful partnership with fairly compensated landholders who accept the imposition of giant towers and high voltage lines on their farms for the good of a country racing to replace fossil fuels with green energy? Or will it be forced upon them with threats, trickery, security guards and a tangle of lawyers?

Tensions high

Some farmers and community leaders in Victoria can see how it will go because security officers and police already appear at community engagement meetings and transmission companies have called off public information events due to security concerns.

A convoy of farmers blocking transmission workers’ access to a farm north of Ballarat in 2022 signalled the depth of feeling – and views have only hardened since then with placard-waving farmers arriving at public meetings on tractors and fire trucks. It has become so heated that Chris Sounness, the chief executive of the Wimmera Southern Mallee Development organisation in western Victoria made a plea for calm in his end-of-year letter.

“Threats of violence, guns, and intimidation are unacceptable,” Sounness wrote. “These actions divide us further and make it harder to work towards solutions.

“This anger is real, and it’s fair enough … Yet even in frustration we must respect each other.’’

A tidal wave of change is mooted for this area – wind farms, mineral sand mines and the hotly contested Victoria New South Wales Interconnector West (VNI West), a 240km transmission line from Bulgana, north of Ararat, to Kerang in the state’s north.

Sounness pleads with the community to stay open-minded; change is coming and the region should capture the benefits and minimise the negatives.

“Building trust won’t be easy but it starts with transparent, meaningful engagement,’’ he says.

After four years of struggle, some farmers along the proposed transmission routes have moved beyond notions of engagement and trust. They’ve tried legal challenges. They’ve appealed to politicians. They’ve been shut-out of the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal after the state government closed third-party appeals against renewables projects.

So now some have vowed to take the battle to their locked farm gates if necessary.

A map of the proposed VNI West route has been updated by the community to denote the landholders opposing it – the document now features an angry red scar of resistance. Farmer and VNI opponent Glenden Watts explains: “These are the landholders who have signed a declaration to not host or be involved in any renewable generation.”

The Victorian government’s attempt to placate landholders by upping compensation to $200,000 per kilometre of transmission lines to be paid in instalments over 25 years, on top of easement payments, hasn’t shifted the mood.

Transmission Company Victoria says it has secured land-access agreements for more than 130 of the approximately 250 properties along the preferred easement. “We’re actively incorporating farmers’ feedback into the design process, including on the best location for transmission towers,’’ a spokesperson says.

Opponents dismiss consultation as a box-ticking exercise. “They say they want to hear your concerns, want to discuss it and make it work for you,” Watts says. “So you have a meeting to discuss it and nothing changes. They just do what they’re going to do anyway. People have tried to do the right thing and realised that it makes absolutely no difference and they’ve had a gutful.’’

Further south in Myrniong, farmer Nathan Lidgett says landholders are also refusing access to AusNet contractors scoping out the Western Renewables Link, the proposed 190km line from Sydenham in Melbourne’s northwest that connects with VNI west at Bulgana.

In response to questions, AusNet does not reveal how many of approximately 200 landholders have signed access agreements but says it is working closely with the “majority” and has secured voluntary access agreements with “many” properties for planning purposes. As a result of feedback, 95 changes have been made to the route and many towers moved.

Access battles

Lidgett released a video in August of AusNet workers wearing body cameras cutting the padlock on a neighbour’s property to gain access without permission.

When challenged, workers cited legislation that empowered transmission companies to access private land. AusNet says every attempt was made to negotiate access before it exercised powers to enter a property.

Lidgett also posted photographs of security guards stationed on his nature strip as contractors undertook survey work about 400m up the road. “Is this what the transition to renewable energy means to regional Australia?” he wrote. “Corporate responsibility and social licence disappear, replaced by standover tactics and intimidation.”

Why would they bring security guards? “We’ve been vocally against the project for four years and they’ve been denied access to our properties,’’ Lidgett says. “But in that instance, I would say it’s more intimidation than anything else. It’s been overkill from the start. Look, if it was the only route to move this energy, we’d be more compliant. But this isn’t the right route or the right process.”

Opponents say the lines on towers up to 80 metres tall will traverse high-risk bushfire areas, have an impact on prime agricultural land and cut through native vegetation.

Similar concerns have been raised about the recently approved HumeLink route through southern NSW where landholders have unsuccessfully pushed Transgrid to build the 365km line underground.

Transgrid says it has now secured land access agreements with 90 per cent of private landholders. The rest are deep in the weeds of the compulsory-acquisition process. Fourth-generation Snowy Valleys landholder Dave Purcell says he doesn’t know what his farm will look like once Transgrid has finished with it. His property at Wondalga in the foothills of Batlow already has 11 330kV lines on smaller towers built in the 1970s.

Along the route connecting Wagga Wagga, Maragle and Bannaby, most of the new 500kV Humelink lines will be constructed parallel to the existing easement - but not in Purcell’s case. “We’re told that 11 new towers will not go parallel but are on a different trajectory,’’ he says, trying to picture the easements and access roads, the creeping footprint of towers and cobwebbing of wires.

“It will ruin the property. We’ll have 10 towers (up to 76m high) on 500 acres (202ha). Even they said they’ve never seen a property as affected as ours but the compensation we’ve been offered doesn’t reflect that. For us it’s quite emotional because it’s a property that’s been so tightly held in the family.’’

Transgrid says a change to the route avoided 10 other properties but meant it now did not run parallel to the existing easement around the Purcells’ property.

Transgrid chief executive Brett Redman has previously acknowledged the significant impact on landowners who have lived and worked on their properties for many generations: “I can’t shy away from that,” he says. “Money alone will not compensate for it.’’

Priorities collide

There are two conflicting issues at the heart of the transmission rollout: companies on tight deadlines to construct critical energy infrastructure at the lowest cost require land that quite often runs through agricultural areas, native habitat or near family homes.

For some landholders it’s no big deal: access payments and compensation help droughtproof their properties and the impacts of a few towers built out of sight on back paddocks are negligible. Others planning their own wind or solar farms need the transmission infrastructure.

Farmers with livestock, difficult terrain and more complex practices face greater impacts on their businesses. Petersen says he accepted that the new EnergyConnect line would go through his property because he already had a smaller 330kV line.

“It makes sense to go alongside the existing line, I get that,’’ he says as we drive along the new easement to a hilltop with broad views over wheat and canola country.

Compensation negotiations for the 70m-wide easements are confidential but people talk and Petersen soon discovered that other landholders were being offered more than he was. He still hasn’t come to an agreement with Transgrid and has taken the compensation fight to the Land and Environment Court.

Gittoes says the initial offer was “very low” and did not reflect what other less impacted properties were receiving. “The Petersen property is probably the most affected that I came across on the project,’’ Petersen’s lawyer says.

In the meantime, as his case works through the court, Petersen’s experience will only add to the fears of other landholders on different routes. This is not just a case of farm gates being left open.

He looks at the fence the contractors built along the easement in the middle of a paddock and tells how lambs kept getting through the fence and becoming separated from their mothers during a time of high milk production. Some ewes developed mastitis, an udder infection, and by July he’d lost 23 ewes from that paddock.

“I didn’t want the fence and as far as I know I am the only landholder they have done that to,’’ he says. “They thought they knew more than I did about my property and look what happened. At the very least I’d like an apology.’’

In response to questions Transgrid says any loss of livestock is unacceptable and it “acknowledges the significant stress this caused Mr Petersen”.

The spokesperson says the fence was constructed to protect livestock near the construction area and that the project team was “working closely” with Petersen. He lists the other issues he’s had: lambs getting stuck in piles of timber left in the paddock; contractors ignoring his biosecurity plan and trying to enter with dirty vehicles containing weed seeds; the endless “miscommunication” – he tells of notifying his liaison contact when he intended to spray near the easement only to have workers turn up anyway. It was one such incident that led to the police complaint.

Other landholders complain of similar communication problems. Cummins says he asked for 24 hours’ notice when contractors would be on his property but was told that wouldn’t happen.

Another property owner, who did not wish to be named, says lack of transparency during the negotiating process was a big issue, along with contractors regularly trying to bully their way on to the property. “If you give them an inch they will walk over you,” the property owner says. “It takes you to the point of breaking quite often.’’

Farmer Charles Kingston, who has about seven half-constructed towers across his land, the closest 300 metres from the family home, says workers seemed to do what they want and then blame it on miscommunication. “We have a property management plan but they haven’t stuck to it,’’ he says.

Gittoes says Transgrid’s priority is to get the project done. “It’s not to work with landholders, it’s not to try to reduce any impact on their property,” he says. “They’ve got a budget to meet and a timeline that supersedes any agreement.”

Transgrid said it takes seriously its responsibility to minimise impacts to landholders and is committed to working with them to achieve reasonable outcomes and address individual circumstances. On-site workers are required to comply with property management and biosecurity plans.

“Any complaints are fully investigated and corrective action taken where required,’’ the spokesperson says.

Petersen can barely raise an ironic smile when he hears Transgrid’s response.

This project was never bogged down in the sort of controversy that has delayed HumeLink and the two Victorian transmission routes. Farmers from the Wagga Wagga end who speak to The Weekend Australian say they went into the process in good faith but came out feeling burnt.

‘We never tried to stop it,’’ Richard Carn says. “We just wanted to be treated fairly.’’

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout