China’s iron ore play could cut prices

The decision to strip the Australian companies, as well as a nearby deposit belonging to Socrates Vasiliades’ Avima, in favour of unknown Congolese-registered company Sangha Mining Development Sasu, still can’t be directly attributed to Chinese interests.

There are enough in-country rumours to suggest that’s the case, however, according to both companies — and last week Jeune Afrique Business reported Sangha Mining was 80 per cent controlled by Chinese businessman Huo Yan, quoting a Congolese ministry official as saying it was owned by a “consortium of Chinese companies”.

Taken together with the China-backed group pushing ahead with the development of the giant Simandou deposit in Guinea, it’s clear there’s a renewed push growing in Africa to win some of the riches that have flowed to Brazil and Australia from China’s economic growth.

There is, to be fair, some justification in Congo’s argument that Sundance has failed to develop the mine in a timely fashion (it’s an argument you’ll hear from long-suffering Sundance shareholders as well).

The project has effectively been moribund for some time. Its development was first interrupted by the tragic death of Sundance’s board in a plane crash in 2010, then by a two-year takeover saga from 2011 involving privately owned Chinese company Hanlong Mining — which eventually culminated the arrest and execution of Hanlong boss Liu Han in 2015 by Chinese authorities.

And most recently it has been stalled by Sundance’s flirtation with another source of private Chinese capital, this time through former ASX-listed AustSino Resources, which kicked off in late 2018 and dragged on for another two years before ending in failure.

And overriding all of them is the iron ore price fall that stalled pretty much all new iron ore developments from 2013.

While the reasons for the delays are legitimate, it is easy to understand the frustration of the government of Congo as iron ore prices rose, particularly if the new proponents are waving around the promise of easy and cheap money from Chinese banks and infrastructure developers.

Even if Chinese interests are behind the push to strip Sundance, Equatorial and Avima of their deposits, it need not be an anti-Australian conspiracy fronted by Chinese authorities and state-owned companies.

Over the past decade Sundance has taken enough Chinese counterparties through due diligence that any one of a number of them could have decided to seize the opportunity and grab it for themselves, before passing the construction contracts out to Chinese SOEs in exchange for debt funding.

Taken alone, Sundance’s 40 million tonne a year Mbalam-Nabeba project wouldn’t shift the dial on global iron ore supply. But adding Avima and Bandondo, through a spur line from the 570km rail line through Cameroon already needed to ship Mbalam-Nabeba iron ore to the market, turns the region into a 100 million tonne a year iron ore province.

And sitting within easy reach of that same spur line is the giant Belinga deposit in Gabon, once controlled by China Machinery Engineering Corp, then briefly by BHP until it pulled out of African iron ore in 2013, and now back in the hands of the Gabonese government.

There has never been a resource or reserve put on Belinga, but it is reputedly one of the biggest untapped deposits around, potentially with more than a billion tonnes of high grade iron ore.

Even at 100 million tonnes a year, the region would still not threaten the Pilbara’s dominance as the biggest supplier of iron ore to China. And at a total development cost of $7bn to 9bn, it would still be a risky proposition outside of boom time iron ore prices.

But when you add the renewed push for the development of the Simandou deposit in Guinea — half-controlled by a consortium led by Singaporean shipping and mining conglomerate Winning International Group that includes China’s Yantai Port Group, with the other half controlled by a joint venture between Rio Tinto and China’s Chinalco — a shape begins to appear in China’s African iron ore ambitions.

The Winning consortium is said to be closing on a debt deal to fund the $US14bn cost of building its mines and the 700km rail and port infrastructure needed to bring Simandou into production, planning to have first ore on ship by 2025.

That will force Rio and Chinalco to get their half of the deposit into production, or sell out to someone who will.

Combined, the two halves of Simandou could easily support an operation shipping between 150 and 200 million tonnes of high grade iron ore a year — again, not enough to push the Pilbara from the market, but certainly enough to add competitive tension to the iron ore market.

Another source of supply

If that was joined by another 100 million tonnes from Congo and Cameroon, you would effectively introduce another source of supply — equivalent in tonnage to Vale and BHP, at up to 300 million tonnes a year — into the market.

There remains substantial doubt whether any of those African mines will hit the market. While some gold, copper and base metals mines have been able to prosper in west Africa, establishing the massive infrastructure and skilled workforces needed for bulk commodity mining has proven far more difficult, and is likely to do so again.

But the beauty of the situation for China is that it doesn’t necessarily even have to ensure those projects are built. Even the threat could be enough to force more tonnes into the market from the iron ore majors, bringing down the price.

Remember that China buys more than a billion tonnes of iron ore a year. A $US1 a tonne price drop over the year saves its steel mills $US1bn. Bring the price back down to $US70/tonne and another $US80bn flows to the bottom line of its steel industry.

Part of the reason for the price spike in late 2020 was Vale’s announcement it would miss production targets for the year, and only slowly ramp up production in 2021 to between 315 million and 335 million tonnes.

At these prices Vale needs to be in no hurry to reach its peak production target of 400 to 450 million tonnes a year — it is making more money now than it would have been if it was still producing at its 2018 rate of 380 million tonnes.

But faced with the threat of new competitors from Africa, Vale may well accelerate those plans, accepting lower prices as the price for making new entries to the market more difficult.

BHP, Fortescue and Gina Rinehart’s Roy Hill have a combined 90 million tonne a year capacity expansions through Port Hedland in the pipeline, and Rio has the ability to export 360 million tonnes from the Pilbara through its port and rail network, well above the 330 million tonnes likely to be shipped in 2020.

Combined, the majors could flood the market with additional tonnes, making the entry of African iron ore a very dicey prospect from a strictly commercial point of view. Which is largely why new African mines have struggled to win financial backing so far.

What is not clear, however, is whether China’s current anger with Australia will play into the equation.

China Inc would be taking a risk that the infrastructure bills worth $US25bn or more needed to open up new provinces in Africa would pay off in the long term. Whether it could successfully operate those massive port, rail and mine networks in Africa’s uncertain political and social environment is a bigger risk.

But China is prepared to let its industry wear the financial cost of its anger with Canberra. The shadow ban on Australian metallurgical coal is costing its steel mills dearly. And the spiralling domestic cost of thermal coal, again partly the result of Beijing’s war trade on Australia, has reportedly led to shortages and blackouts.

Iron ore has so far remained immune from the trade war, as Australia supplies more than 60 per cent of China’s imports.

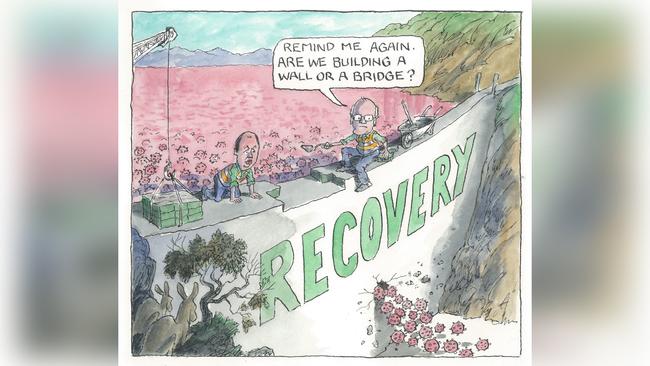

But China’s leaders might decide $US25bn is an easy price to pay to ensure it has more leverage. Or the threat might be enough to encourage further expansion in Australia and Brazil. Either way the iron ore price comes down.

The confiscation of iron ore projects belonging to ASX-listed Sundance Resources and Equatorial Resource by the Republic of Congo should sound fresh warning bells that China is getting serious about opening up new iron ore provinces that would reduce its reliance on Australia’s Pilbara region.