How BHP’s rogue ore train went off the rails

In the early hours of Monday morning, just before sunrise, BHP’s remote operations centre was in crisis.

In the early hours of Monday morning, just before sunrise, BHP’s remote operations centre in the heart of Perth’s CBD was in crisis.

A massive, fully laden iron ore train was out of control and hurtling across the Pilbara without anyone at the controls, at speeds well above anything seen in the region before.

The safety measures designed to bring the train to a safe halt in such circumstances had failed, and now the runaway train was careering towards Port Hedland.

It fell to the team in BHP’s integrated remote operations centre, or IROC, to make a decision that would create a damage bill of millions of dollars and disrupt one of the most profitable and important businesses in Australia.

IROC, which sits within the 45-storey BHP headquarters that dominates the Perth skyline, features banks of computer monitors relaying real-time data from the company’s expansive Pilbara iron ore mines, railways and port operations back to a team constantly working to improve scheduling and fleet management.

Jobs in IROC are part of the new generation of mining roles carried out in the relative comfort of a modern office in Perth — in this instance, with stunning views of the Swan River — rather than out in the heat and dust of the Pilbara.

As the city began to wake to a new week, those BHP employees at their desks in Perth were facing an unprecedented emergency. With the train continuing to build speed and closing in on another train further up the track, the workers had a narrow window of opportunity to take action.

From the Perth office, the operators used their computers to “throw the points” and switch the speeding train to a different line, triggering the derailment.

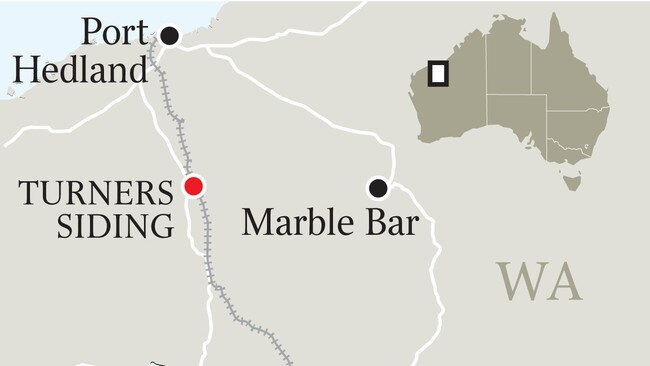

During the 50 minutes the train was on the loose, it covered 92km — giving it an average speed over that period of just over 110km/h.

But given the substantial amount of time it takes for the monster trains to build up speed, there are estimates the train would have reached speeds of as much as 160km/h — double the top operating speeds normally seen among the Pilbara trains — by the time it derailed.

The speed of the train at the time of the accident was evident in the footage of the scattered and twisted rail wagons that emerged in the following days.

Speaking at the company’s annual general meeting in Adelaide on Thursday, BHP chief executive Andrew Mackenzie praised the quick thinking of the workers who found a way to bring the train to a stop.

“[They] realised that if they didn’t force the derailment of this train, it could have caused an awful lot more damage and could have been a real safety risk,” Mr Mackenzie said. “So they threw the points at a time when they knew it was moving quickly to derail the train and stop it before it damaged anybody. They made it safe and nobody was hurt.”

The accident is an expensive one for BHP in more ways than one. On top of the damaged train and wagons, the incident has forced BHP to shut its entire Pilbara rail network, disrupting a business that generated just under $34.5 million a day in earnings for the company last year.

BHP is also facing potentially millions of dollars in fines if it is found to have breached national rail safety laws. And then there is the reputational damage to BHP, which is still working to recover from the 2015 disaster at its Samarco joint venture in Brazil. The outcome of the investigation into the causes of the accident will also go a long way to determining the pace at which automation takes hold.

If the investigators currently poring over the crash site find it was caused by human error, it will probably accelerate the efforts of BHP and other heavy haul rail operators to follow the lead of Rio Tinto and automate their entire fleets.

The CFMEU, however, has already used the accident to call for the return of a second driver in every train across the Pilbara — unwinding a cut that was made about two decades ago.

(According to sources in the Pilbara, the driver of the ill-fated train was not a member of the union. Talk in the Pilbara is that the driver is to face a BHP disciplinary hearing in coming days.)

Even before the formal causes of the accident are known, the incident has prompted rail operators across the country to pause and review their own equipment and processes.

Other miners have reacted to the news with a combination of shock that such a situation could occur, and relief that it didn’t happen to them. While the other miners are confident they have the systems and equipment to prevent a repeat of such an episode, BHP would have felt the same a week ago.

Among the key questions needing to be answered is what happened to the train’s brakes. Were they properly applied before the driver exited the cabin to inspect an issue with one of the train’s wagons? If so, how did the brakes release while he was out?

Then there is the question of the train’s “dead man’s switch” — the button inside every train cabin that emits an alarm at frequent intervals to ensure that the driver is still awake and functioning. If the switch is not pressed, the train should stop automatically.

Dead man’s switches generally deactivate when a locomotive’s handbrake is applied, which could explain why the system failed to kick in when the train started to run away. If that is the case, it points to a major failure of the train’s brakes.

Other trains in the Pilbara also have controls designed to automatically kick in and slow a train if it exceeds set speeds. Again, any such measures on the BHP train appear to have failed.

Older train systems such as that used by BHP require the handbrake to be applied to every individual locomotive and wagon — a time-consuming process given the scale of the Pilbara trains. In contrast, more modern iron ore trains are designed to have all handbrakes applied simultaneously through a single action.

BHP has so far been tight-lipped about the potential causes of the disaster.

But it was interesting, firstly, that Mr Mackenzie praised the work of those remote operators in Perth who managed to derail the train and, second, that he said the company was already looking at investments in its rail network before the series of events that played out on Monday. That suggests there is likely to be more automation and remote operation at BHP, rather than less.

The train wreckage had been cleared from the site as of yesterday, with BHP confident of resuming rail operations early next week. But until there is a clearer picture of the reasons for the disaster, questions will persist even after the trains resume their journeys.