$250bn to replace power plants

Australia faces a $250 billion bill to replace its ageing power generation fleet.

Australia faces a $250 billion bill to replace its ageing power generation fleet amid a long-running political battle over the nation’s energy and environment policy, according to estimates by AGL Energy.

Amid mounting pressure to extend the life of its coal-fired power fleet, one of Australia’s biggest energy retailers said advances in the cost and capacity of producing wind and solar power were rapidly beating new coal generation — even without a price on carbon — and were driving the preference for renewable energy investment.

AGL chief financial officer Brett Redman estimated that replacing the generation fleet with largely renewable capacity would cost $150bn, with another $100bn for storage and firming capacity — which includes batteries and gas-fired power plants.

The figure has come to light amid a continuing clamour from energy companies and customers for certainty about policy so that they can take the long-term investment decisions to replace retiring capacity and meet new demand.

The estimate was made in an AGL presentation to investors that suggested the market could move from being one dominated by coal-fired base load power to one dominated by “storable renewables”.

Improvements in the cost and capacity of batteries would be the leading indicator for the speed and cost of that change, Mr Redman said.

“We think it’s pretty unambiguous — even if you don’t accept the scientific orthodoxy on climate change, it increasingly appears that technological developments in renewables will outpace the efficiency of thermal energy in coming years,” he said in a previously unreported presentation to the Macquarie investor conference this year.

The investment estimate suggests nearly $8bn a year will have to be spent on upgrading or replacing Australia’s generating capacity for the next 32 years, compared with around $8.7bn in spending on new projects committed this year, as the industry races to catch up from a two-year investment strike when the Renewable Energy Target was under review.

AGL’s investment plans are under pressure from the federal government, which is attempting to rein in spiralling energy prices while still meeting its international obligations to cut carbon pollution. AGL chief executive Andy Vesey this week agreed to a request from Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull to consider extending the life of its 1900MW Liddell coal-fired power station beyond its 2022 closure date.

Mr Vesey said he would take the proposal to the AGL board within 90 days but reiterated the company’s plan to develop 1000MW of new renewable generation capacity — including wind, solar and hydro — remained its preference.

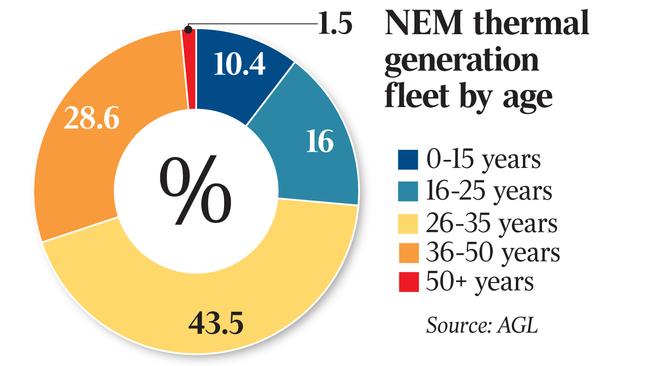

AGL said previously that 75 per cent of Australia’s existing generation capacity was already past its intended use-by date and the company planned to close the last of its coal-fired plants — Loy Yang A in Victoria — by 2050.

AGL has set up a $2bn-$3bn Powering Australian Renewables Fund, with $200m of its own equity and $800m from the Queensland Investment Corporation and the federal government’s Future Fund to invest in new capacity.

Its investments include the planned Cooper’s Gap wind farm in Queensland — set to be Australia’s biggest at 453MW — and the 200MW Silverton wind farm in outback NSW.

The Australian can reveal that AGL will contract to pay the PARF investors $60/MWh for the power from those projects for periods of up to 20 years, taking the risk that it can sell the power at higher prices to its retail and commercial customer base.

Company estimates are that it costs $55/MWh to install commercial wind farms, with another $25/MWh to add “firming” capacity as required under recommendations from the Finkel Review.

But new coal capacity is estimated to cost $100-$130MWh — excluding any future cost of carbon — while large-scale solar farms carry a comparable cost after including more expensive firming capacity.

But because of the high costs and long lead time to develop new base load coal capacity, such as high efficiency, low emissions (HELE) coal plants, those plants were likely to be even less competitive with renewables once they came on line after a projected seven or eight-year development period.

Australian Energy Council chief executive Matthew Warren said the rapid advances in cost and capacity of renewables had ensured they would be the preferred form of new generation.

“They (wind and solar farms) are away,” Mr Warren said. “They are just going to keep getting built.”

Energy companies had been urging the government to adopt the clean energy target recommended by Chief Scientist Alan Finkel. But they are facing continuing uncertainty amid signs from Canberra that the CET will be remodelled to focus on reliability and base load generation — rather than on carbon reduction — in a change potentially allowing new HELE plants.

But Mr Warren said the CET should be seen as a scheme to direct investment in new firming capacity, rather than in renewables.

“Renewable energy is now the cheapest part of the system, and the bit that needs subsidising will be the firming bits, such as coal and the like,’’ he said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout