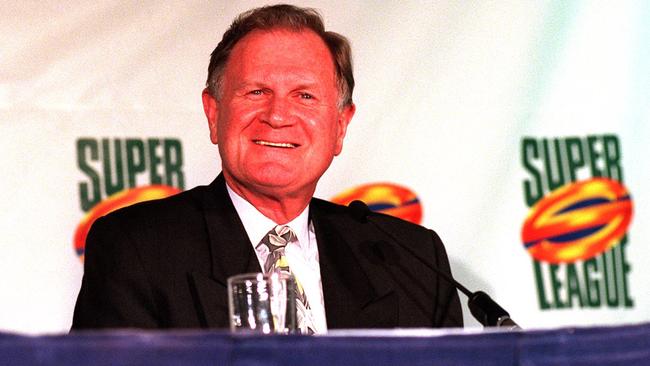

As Rupert Murdoch’s right-hand man, Ken Cowley helped launch The Australian

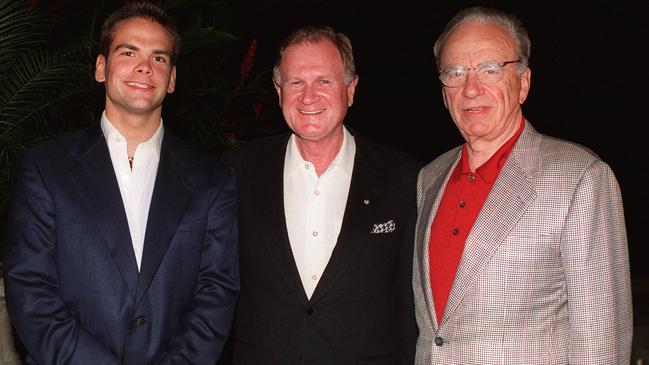

As Rupert Murdoch changed Australian publishing and launched News Corp to the world, Ken Cowley was at his side.

When Rupert Murdoch first published The Australian on July 15, 1964, helping to deliver his vision for a national daily newspaper was his right-hand man and close confidant Ken Cowley.

There were more than a dozen national papers in Britain, most delivered by trains across a nation not 1000km from tip to toe, but Murdoch wanted to give a voice to a country whose inhabitants might live more than 5000km apart.

Others had talked, mostly timidly, of a national newspaper since the mid-1950s but were daunted by the logistics. Risk averse, they could see its significant costs and the obvious financial dangers.

The original plan was for a newspaper published in Canberra, but within days the ambitious Murdoch had conceived the idea of a national newspaper published from Canberra, with copies printed in Sydney and Melbourne using plates flown to those capitals.

And that newspaper was the same as the one you hold in your hands today, or are reading on your tablet or mobile phone.

Cowley, who has died aged 87, operated as Murdoch’s loyal colleague in a series of senior roles to help build a publishing, broadcasting and transport empire across Australia and New Zealand.

Cowley would later describe his years with the business as a “magic-carpet ride”.

Cowley was born on November 17, 1934, to Edward (Ted) Cowley, an English migrant, and his wife, Phyllis. There were four sons, and as they grew up in Sydney’s Bankstown in the 1940s the family’s life could best be described as hardscrabble. Nonetheless, Cowley would describe it as “an idyllic childhood”. The boys and their parents lived for years in an old military tent as their modest house was built. Cowley described it as basic: “Two bedrooms, an outdoor dunny and external bathroom.”

Cowley’s brother John recalled those days: “When we were young blokes, if you ever got bored you didn’t rush out and get drunk or go on drugs, you’d put on a backpack and go walking through the bush with your mates and your dogs for 10 or 20 miles and swim in the creek.”

Cowley would describe his father as a bus driver and delivery driver, but he also worked at the Hawker de Havilland factory that was built at Bankstown Airport during the war.

In 1955 Ted Cowley, aged 45, was killed at the airport. He was in one of two light planes that collided as they prepared to land, crashing 100m to the ground. The only survivor was a young David Lloyd Jones, soon to be the chairman of the chain of stores bearing his family’s name.

Ted had been keen on his sons having a trade and Ken, who had gone to Bankstown High School, studied printing at Sydney Technical College.

He later worked on a free local newspaper while managing a picture theatre. He was invited to play rugby for a Canberra team and the club found him work on The Canberra Times. Cowley and his new wife Maureen liked Canberra but, despite its rapid growth and potential, he found the national capital slumbering and served by a newspaper unwilling to wake it up.

A second season saw the Cowleys move to live in Canberra permanently. Even with his limited experience on the free newspaper, Cowley understood how important to their audience and powerful newspapers could be. “So I came up with the mad idea. That’s when I started to think about doing the newspaper for ourselves … I could tell there was a big opportunity,” he recalled to former News Corp editor Mark Day in 2014.

“I thought there’s a big space out there, and there were no magazines or anything; it was just radio and The Canberra Times. No television,” Cowley said.

“And because they had a monopoly, (The Canberra Times) had become a bit slack. There was virtually no reporting of parliament in it – people relied more on The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age.”

Cowley could see a bigger picture, and that the national capital could be the place for a vibrant newspaper that reported on it and to the nation.

He was surprised by The Canberra Times’ reluctance to report on the federal parliament, which he saw as bread-and-butter journalism in a town dominated by government departments and the public servants they employed. Back then, they turned to interstate newspapers for such news.

One day, Cowley took The Canberra Times reporter Eric Walsh out for a beer to talk about a new newspaper for the town. “I remember before I hired Eric Walsh, we had a session in the pub one day, and that’s when he gave me good advice on what we could publish that wasn’t being published and what the opportunities were in sport … politics, too, but sport as well. No one was covering the public service – there were big gaps everywhere.”

Cowley soon hired Walsh, who went on to a legendary career in the parliamentary gallery and was press adviser to prime minister Gough Whitlam.

Cowley settled on his masthead. It would be The Territorial. The weekly, and later biweekly, newspaper quickly became a family affair; two of the Cowley brothers, Les and John, would work there as printers.

Being interviewed for the Old Parliament House political and parliamentary oral history project in 2010, Walsh recalled how the name came about. “The reason it was called The Territorial was that Arthur Shakespeare, who owned The Canberra Times … was terrified that one of the big (publishers) would come in and start, so he had about three pages of names of newspapers registered as him. So, if anybody wanted to start a newspaper, they couldn’t call it The Sun or The Courier-Sun or The Herald or The Herald Sun.”

He described how the newspaper rapidly grew from eight pages to 16 to 32. It was delivered free to sporting clubs and RSLs and thrown over suburban fences. Its future was limited only by its press capacity and Cowley’s lack of capital, despite the fact he paid himself just £30 a week, with the company’s profits being reinvested in the business.

John Cowley recalled: “I used to print the paper, help Ken compose it, sweep the floor, melt the metal (recycling the hot metal type), sell the ads to the second-hand and new-car dealers, and I used to deliver the papers. It was a big family affair.”

In 1962, through a contact, Cowley organised to be shown through the press hall of the Daily Mirror in Holt Street in the heart of Sydney’s Surry Hills. Murdoch had bought the newspaper from Fairfax three years earlier. In an unchanging story he repeated over the years, Cowley described what happened next: “We’d just finished the tour and they said there was a message that Mr Murdoch wanted to see me. It was the first time I’d met him and he had a copy of my newspaper on his desk. He asked: ‘Who edits it and who writes all this anti-Menzies stuff?’ ”

Cowley explained that he wrote most of the stories, particularly those critical of then prime minister Robert Menzies, and that Canberra’s public servants lapped it up.

Perhaps with a national daily in mind, even if distantly, Murdoch, then 31, asked Cowley, 28, if he could buy The Territorial. Cowley declined, but the pair stayed in touch.

Cowley always said it had not been his idea to start a national daily, but it had been on his mind. “A lot of people were talking about the role of a national newspaper then … so I talked to Rupert about it, and my having some sort of role in it,” Cowley remembers. “But of course, at the speed Rupert travels, he grabbed the idea and burned me off in about three days.”

By early 1964, Murdoch’s board had signed off on secret plans to publish a newspaper from Canberra. A property was secured in Mort Street, as was a 40-year-old printing press. By March, Murdoch had hired the noisy, mercurial, hard-drinking former Australian Financial Review editor Maxwell Newton to run his newspaper and staff it with the best journalists he could find. Like Newton himself, these could be unorthodox: he had seen Walter Kommer give a speech four years earlier. Kommer had been a Dutch soldier who fought the Japanese and had then trained as an economist. He was hired as a reporter and ultimately replaced Newton as editor.

While The Australian took shape – after Murdoch had purchased the Cowleys’ company and hired The Territorial’s owner-editor-manager-printer to oversee its production (Cowley had been offered an editorial role but stuck with what he knew best) – word of this interloper in the national capital spread and Shakespeare enacted a long-dormant plan: he would sell The Canberra Times to the intruder’s most powerful opponent. Days later his newspaper was purchased by Fairfax, which installed a new editor and management.

Murdoch, Cowley and Newton took on the challenger and, driven by Murdoch, the lead time for the launch of The Australian was slashed. Newton observed in 1989: “In those terrible hours and days, when we realised our predicament, Rupert showed some of the steel, the gambler’s recklessness and the foresight that have since grown to such maturity on the world stage.”

The original plan had been to secure a foothold for The Australian in Canberra, then expand it first to Sydney and Melbourne and then to the other states. Challenged by Fairfax, Murdoch pushed “go” on his national daily. The Mort Street building was unfinished, but the planned September launch was brought forward to July 14. Despite early dummy editions – just half the pagination of the proposed newspaper – not having been printed in time, The Australian’s launch edition carried a July 15, 1964, date and sold out.

With untested distribution networks and regular fogs grounding planes at Canberra, sales soon settled at fewer than 80,000, a level at which The Australian would be unprofitable. But no deadline was set for profitability. The newspaper was moved to Sydney in 1967 and Cowley moved up the ranks of News Limited at Holt Street while The Australian’s position also improved.

Cowley was soon elevated from production manager of The Australian to overall production boss of News Limited’s Sydney operations, which then included The Daily Telegraph, the Sunday Telegraph, the Daily Mirror and Sunday Mirror in what was then described as the most competitive newspaper market in the world.

Not long after, he was deputy general manager and by 1980 was News Limited’s chief executive.

It was in this role that his management style and skills would soon be tested. So-called new technology – the computerisation of typesetting, which had been developed not long after World War II – was slow to come to what were then highly unionised newspapers in Australia and the UK, and Cowley was to play a role in both their acceptance here and the London revolution at Wapping in 1986 that brought about the end of Fleet Street and its militant printers, who for more than a century had controlled, and restricted, publishing.

There had been unrest about the introduction of computers on the editorial floors of Australia’s newspapers and it had sparked a six-week nationwide strike by journalists in 1980. At The Australian, things never really calmed down with stop-work meetings called at crucial times in the production cycle. Sometimes the journalists would just walk out. Cowley saw computerisation as essential to the changing economics of publishing, particularly in the case of The Australian, which was still to register a profit.

On a trip to London, he discussed with Murdoch the issue he felt was strangling The Australian. On a subsequent call, the boss’s instructions to Cowley were clear: “Fix it or close it. And don’t call me back.”

Back home, Cowley brought matters to a head, sacking 42 staff. Such brinkmanship was out of character for him and he had lost sleep over it the night before. The remaining staff walked off for a stop-working meeting.

As they met in the carpark across the road, Cowley sent them a message via an editor: “If you are not back at work in five minutes The Australian will be closed.”

A few staff dribbled back after a couple of minutes. The meeting ended soon after, everyone returned to work and the edition came out that night.

“It was a huge decision and when they had all come back inside I realised what a massive risk I had taken – and I got away with it. If they had not come back I think I might have been hung. I know Rupert said it was my decision, but he might have said that so he could hang me by the bloody thumbs!”

Three years later, Cowley announced that The Australian had made its first profit.

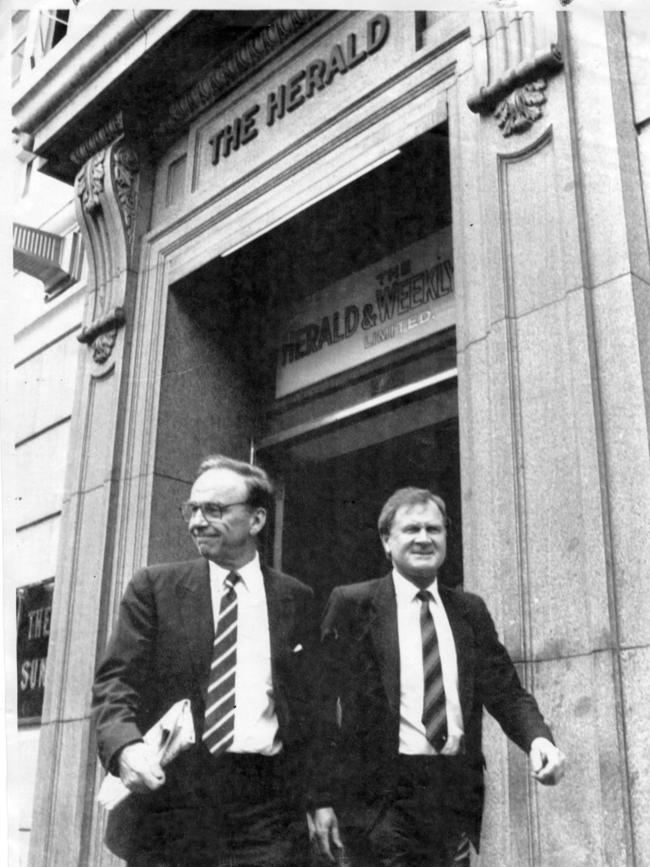

At the end of 1986, News launched a bid to take over the Herald and Weekly Times Group of newspapers – Australia’s biggest. Cowley had doubts about saving Melbourne’s loss-making afternoon newspaper The Herald, of which Murdoch’s father Sir Keith had been editor-in-chief. But he also saw the possibilities.

The following year, addressing a newspaper industry conference, he said: “In February 1987, we concluded the biggest newspaper takeover in the world by acquiring the Herald and Weekly Times Group and its associates for $2.3bn. Our success in this acquisition came because we were determined to secure and advance our position and our future in Australia. Rupert Murdoch has taken on another of the great challenges of his newspaper career with our revamped Melbourne Herald.”

Murdoch did much more than just revamp the legendary Melbourne newspaper. He had soon overhauled the industry. News gave notice that it was ending the agreement that had seen Fairfax and HWT jointly publish a thin, underfunded newspaper, The Sunday Press, to act as a spoiler to keep shut Victoria’s Sunday market. In 1989, News announced it would be launching not one but two new Sunday newspapers – the tabloid Sunday Sun and the broadsheet Sunday Herald. Fairfax responding with its broadsheet The Sunday Age. All three started life on August 20, 1989.

The following year, The Herald and The Sun in Melbourne (as The Herald-Sun) and The Daily Telegraph and The Mirror (as The Daily Telegraph-Mirror) merged to be 24-hour newspapers.

As Murdoch’s most trusted executive, Cowley gave him the freedom to expand his media empire overseas knowing the Australian business was in safe hands.

Murdoch’s stable of companies soon included London’s The Sun, The News of the World, The Times and The Sunday Times, the New York Post, New York magazine, San Antonio Express, Boston Herald, 20th Century Fox, HarperCollins, the South China Morning Post and a host of other interests.

At the same time, Cowley developed as one of the most successful and respected chief executives in Australia. His intimate knowledge of every aspect of the industry was indispensable. He knew how to run a newspaper corporation, and understood its intrinsic turbulent nature and its daily dramas. He had good financial and political judgment, and managed his newspaper editors with an astute blend of support and pressure.

He enjoyed a strong relationship with prime ministers on both sides of politics who often sought his judgment on issues that transcended the industry.

Above all, Cowley enjoyed a remarkably long and mutually trusting relationship with Murdoch. It was this relationship that meant Cowley ran the Australian operation with a large degree of autonomy while always alert to Murdoch’s overarching authority.

Cowley also had a deep personal commitment to The Australian, given its inception at the outset of his relationship with Murdoch. As chief executive, he followed the fortunes of the paper closely and was its champion when The Australian faced what he felt was unwarranted criticism from the political class. At critical times, his decisions were pivotal in ensuring the paper’s survival.

He was always anxious to turn the paper into a profit-making concern. And he believed The Australian was not just a valuable asset in the company’s stable but something more – a national instrument for debate and advocacy that would contribute greatly to Australia’s progress.

By 1979, Cowley’s portfolio of responsibilities had expanded. He was joint CEO with Peter Abeles of Ansett Airlines, which Abeles’ TNT and News Limited purchased in 1979, along with which came a share of Channel 10. The airline had been very profitable, but Cowley said he struggled to work with Abeles, whose strategies were later criticised by industry observers and later Ansett executives. Abeles would go to international air shows and return with news that he had bought another plane. Maybe two. How these would fit into Ansett’s fleet was for others to work out. Accordingly, the fleet was dubbed Noah’s Ark. After Abeles left, Cowley ran the airline and would later be closely involved in the negotiations that saw Air New Zealand take full ownership of Ansett.

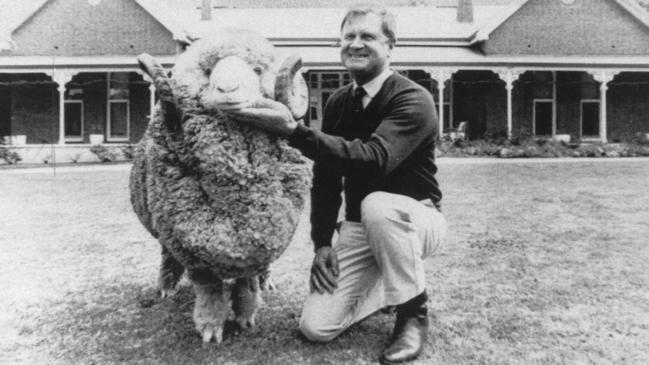

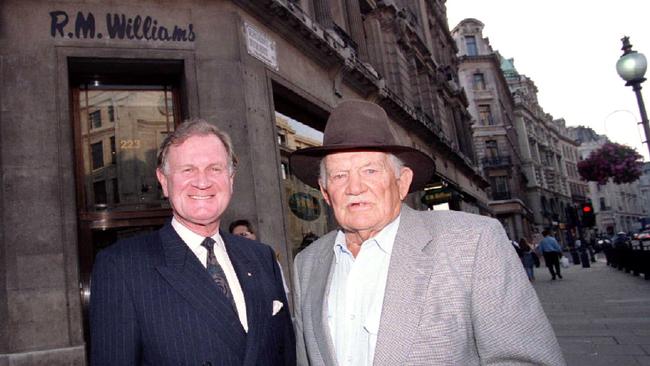

Cowley also took ownership of his friend RM Williams’ uniquely Australian bush outfitter business. His connection with the land had been reinforced when News purchased the merino breeder FS Falkiner and Sons in 1978. Cowley and Williams had helped drive the establishment of the Australian Stockman’s Hall of Fame at Longreach in central Queensland. It was opened in 1988 by the Queen, and Cowley would become its chairman.

Cowley stepped down as executive chairman of News Limited in 1997 and retired from the board in 2011. He also served as a director of the Commonwealth Bank and had been a life governor of the Art Gallery of NSW since 1986. He was awarded an Order of Australia in 1988 for service to the media and to the community.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout