Stubborn purchase of worthless conspiracy theories

OLD opinions can be resistant to reason.

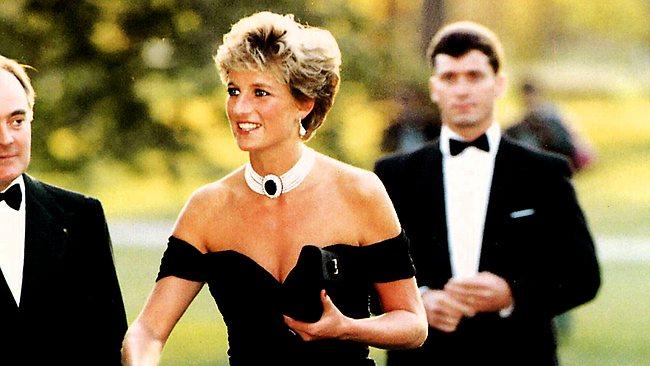

ON the balance of probability, it is safe to say that a drunken French chauffeur was responsible for Princess Diana's death, not a covert intelligence officer driving a white Fiat Uno.

Yet acres of news print, and even more words on the internet, have been devoted to prove the very opposite. The conspiracy theory, defined by British journalist David Aaronovitch as "the attribution of deliberate agency to something that is more likely to be accidental or unintended", is resistant to reason and can defy the finding of inquests and official inquiries.

Good journalism, like good science, must forever be on its guard against reporting assumptions rather than facts. Francis Bacon, the father of modern science, observed that when the intellect is left to its own devices, it falls back on what it anticipates to be true rather than the evidence and "merely glances in passing at experiments and particular events".

"Once the human intellect has adopted an opinion, it draws everything in to confirm and support it," wrote Bacon in Novum Organum in 1642. "If there are more and stronger instances against it, they are overlooked or treated as negligible, or the line is redrawn to shift them out of the way and reject them."

This reluctance to deal with brute facts as they are discovered, even if they disprove the story, is at the heart of The Australian Financial Review's confusion in its recent unproven claims that Rupert Murdoch's News Corporation's former subsidiary NDS had engaged in dirty tricks to bring down its pay-TV rivals. The AFR has suggested among other things that NDS covertly encouraged piracy against pay-TV operator Austar in order to drive down its value so that its rival, Foxtel, 25 per cent-owned by News, could pick it up for a song.

The man at the helm of Austar at the time of the alleged skullduggery, CEO John Porter, said the story was "so farcical that I really don't think it is worthy of my time". He said he had seen no evidence whatsoever that News had promoted pay-TV piracy to damage his business. "Quite to the contrary," he told ABC radio, News had been fighting piracy around the world.

News Limited chief executive Kim Williams called the AFR's claim "laughable". Michael Speck, Australia's foremost anti-piracy expert, said: "It doesn't convince at many levels. There are a number of significant flaws in the assertions and conclusions; so many, in fact, you'd have to treat the entire story with great scepticism."

In an interview with the Global Mail last week, AFR journalist Neil Chenoweth claimed the special privilege of an expert: "I'd think I would be deeply familiar with the history of the company I've been looking at for a long time."

In journalism, as in science, the appeal to expert status as a basis for knowledge is a dangerous move; it is a step back from Aristotelian reason towards the seductive logic of the grassy knoll, an error of reasoning as old as science itself. Chenoweth has indeed become something of a specialist on News Corporation, but has been outspoken in his criticism of the company. It is not inconceivable that personal prejudice, what Bacon calls "the idols of the cave", predetermined the outcome of his investigation. When challenged to furnish evidence for its claims, the AFR falls back on 14,000 leaked emails yet so far has only quoted from a handful of them, and NDS claims even those emails have been taken out of context.

Bacon tells the story of a man who is shown a picture hanging in a temple of a man who had miraculously escaped a shipwreck after making his vows.

"He was asked 'Now do you admit the power of the gods?' He answered with a question; 'Where are the pictures of those who made their vows and then drowned?' "

Nick Cater is editor of The Weekend Australian