‘Our greatest clown’: Bert Newton knew how to make Australians laugh

Bert Newton was an icon of radio, TV and theatre – the last survivor of the medium’s beginnings in this country when it was joyfully makeshift, impromptu and live.

OBITUARY

Bert Newton TV presenter and personality

Born: July 23, 1938, Melbourne; died aged 83, October 30, Melbourne

For more than five and a half decades Bert Newton made Australia laugh — our greatest clown, an icon of radio, TV and, towards the end of his career, theatre. He was our consummate TV host, presenter, compere, and personality, the last survivor of the medium’s beginnings in this country when it was joyfully makeshift, impromptu and live.

In so many ways his career was a celebration of the traditional and increasingly obsolescent notion of TV as a virtual community, an extended family brought together by the same shows, when we argued with the screen, shouted and barracked together, and cackled with ridicule at times so violently we practically tumbled off our sofas.

Newton really was a kind of social presence almost from the time TV began in this country, one of TV’s best known and revered chatting conduits, those cheerful presenters who by talking to the camera negotiate a peaceful compromise between those of us watching and those who are interviewed, or who perform or compete on the screen. Targets of great affection and an equal amount of derision, they are largely taken for granted, even though the subject of extravagant radio, internet, magazine and newspaper coverage. But few had careers like Bert Newton’s, that lasted almost as long as post-war TV itself.

Nevertheless, as a profession, TV presenting, routinely ignored, has received little serious attention, not that it ever seemed to really disturb Newton, unlike Graham Kennedy who often referred to his career in TV as “going second class”, especially when compared to acting, spending his life desperate to be categorised as anything other than a talk-show host. “The best things about television are the free clothes, free haircuts and free wine,’’ was all he had to say about the medium. Kennedy said he couldn’t dance, wasn’t really a singer, and found jokes hard to tell — but he did it better than anyone else. The same, to some extent, was true of Newton.

But it’s easy to ignore the fact that so much of the TV we watch involves presenters like Newton, exemplars of what some might call “consolatory viewing”: the kind that we do when there is nothing else happening, not particularly important but regular. And for that we should be grateful. Talking heads are the mainstay of TV; speaking to us directly from their own well-established personas, they really are the key to the sociability of TV.

And Newton was brilliant at it. For a very long time.

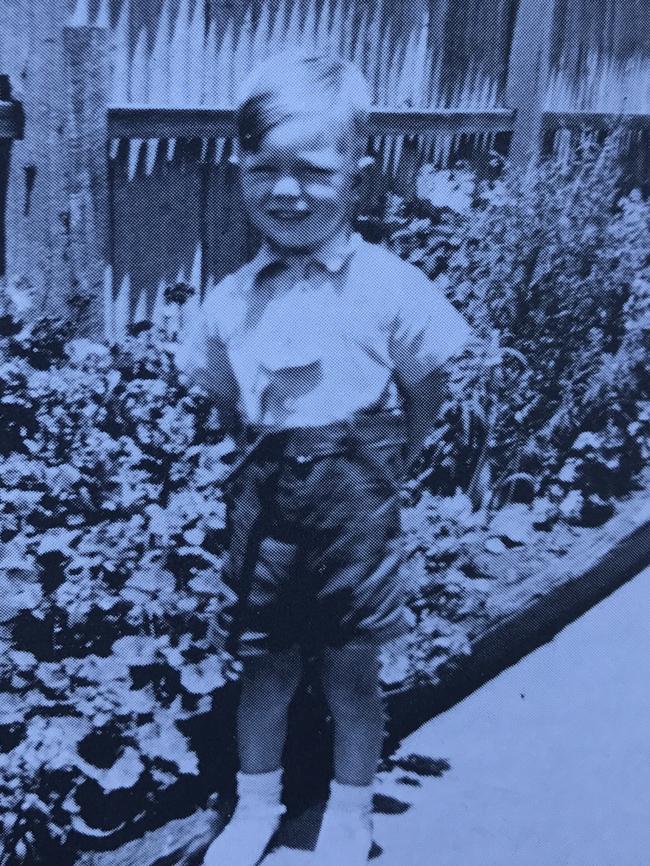

He was born on July 23, 1938 in a private hospital in North Fitzroy, Melbourne, the suburb in which he lived during his early radio and TV career. Newton was the youngest announcer in Melbourne’s radio history when he joined station 3XY after finishing school in 1954, aged 15. He handled every shift on the station at some stage during the 1950s, including the evening programs, considered in the time before TV to be the most prestigious. He became known as Melbourne’s self-labelled “Number One Bachelor Boy” when he conducted 3XY’s Bachelor Club on Tuesday nights, “dedicated to all freedom-loving men”.

He began his TV career at Melbourne’s HSV7, hosting The Late Show but the 19-year-old, unhappy at Seven, went to GTV9 and soon joined Graham Kennedy on the hugely successful In Melbourne Tonight as an announcer and Kennedy’s offsider. Their double act took Melbourne by storm, Newton bringing unparalleled experience in ad libbing with him from his radio days and they performed cross-talk comedy with the immediacy of reminiscing brothers.

In 1974 he married his sweetheart, the singer Patti McGrath, after proposing on the QE2 in a rainstorm at Martinique, in the Caribbean, on Australia Day. Newton, now hugely successful, published an autobiography Bert!: Bert Newton’s Own Story, in 1979.

From 1975 until 1983, Newton worked with Don Lane on his long-running, highly successful program, The Don Lane Show, an inspired mix of celebrity interviews, stunts and buffoonery. In 1976 he also replaced long-running compere Frank Wilson on the popular talent show New Faces and in 1981, with wife Patti, hosted Ford Superquiz.

In 1992 Newton moved to Channel 10 and daytime TV where for the next 14 years he compered Good Morning Australia, an inventive largely ad libbed mix of interviews, music and cooking segments. There, he reinvented morning TV.

There was a hiccup in his career (the survivor journalists loved to say it had endured more resurrections than Lazarus), when, in 1993, it was revealed that Newton owed nearly a million dollars. And that he blamed his financial problems on gambling credit and, as it turned out, those limited employment opportunities though the bad years.

According to press reports his assets at the time included $20 in a Bank of Melbourne account, $1000 in cash, $20,000 worth of household furniture and fittings at a Canterbury address and a $25,000 share in an Alphington property.

It was reported that to avoid bankruptcy he had worked out a deal to pay 40 cents in the dollar on more than half a million dollars debt. He never spoke publicly about the affair at the time and wasn’t even tempted by the attractive money offered by three women’s magazines to tell his story.

“I felt that would have been copping out,” he later told Age journalist Muriel Reddy in 1995, as he prepared to appear in another musical, Beauty and the Beast, which was opening at Melbourne’s Princess Theatre. He played Cogsworth, the snotty butler who is turned into a clock by an enchantress. “It just felt wrong. Any successes I’ve had in life invariably have resulted in gut feeling and any failures I’ve had have really been the times when I’ve gone against my gut feeling.”

He called the public airing of his embarrassment his purgatory but refused to see it as having changed his heart and being. He simply met his commitments and moved on with his show and his life. The story quickly died, but Newton continued to revive his career in unexpected ways.

The breadth of his performing talents, and our appreciation of them, were witnessed by the string of Logie awards – 18 in total, five Gold Logies between 1979 and 1984 – and the reviews of his prominent roles in legendary stage show including The Producers, The Sound of Music, Annie and Wicked (stepping in as the Wizard of Oz at short notice following the sudden death of its star Rob Guest in October 2008).

The community’s regard for Newton is reflected in Victorian Premier Daniel Andrew’s immediate offer on Saturday night to the family of a State funeral in a call to Patti.

Newton was made an MBE by the Queen in 1979 and a Member of the Order of Australia in 2006.

That is the year he returned to the Nine Network to host Bert’s Family Feud and 20 to 1, a show composed of video clips and brief interviews with celebrities held together by Newton’s voice, resonant and full of actorly energy.

In an interview with The Australian’s Trent Dalton to celebrate turning 75, he recalled visiting the grave of an old friend, accompanied by two ageing entertainer colleagues, one a comedian and the other a singer. After paying their respects, the comedian turned to the singer and sighed resolutely: “Hardly worthwhile going home.”

And he remembered an old Melbourne journalist friend who once offered to read him his pre-written obituary, saying it was a good read with plenty of high points … “would be a shame if he missed it.” Newton said his only true regret was that he started in entertainment so young that his closest friends were often 20 years older than him. “Of course, what you soon realise is that you start losing them all.”

He was asked, “How does you do it?” And “Why do you still do it?” Having been on the airwaves and TV screens since he was 11, it was pretty much all he knew, he answered.

It’s easy to understand why for so many years, on so many different but sometimes eerily similar sets, Newton’s guests relaxed on that couch in the studios of Channel 9 or Ten, sometimes arriving straight from premieres, obviously simply delighted to be cajoled, mocked, mimicked, lauded, flattered and charmed by this very funny man.

Few were as adept as Newton at turning conversation into humour, one of the great tricks of the TV host, along with making us believe we are on an intimate footing with everything and everybody in show business. It was the key to his success in radio, too.

He once described himself as “second-stringer, second-banana, feedman and stooge” – and he was all those things – often of course he stole the laughs in those celebrated TV relationships with Kennedy and Lane – but he was also an eloquent and witty speaker and consummate interviewer. He was recognised as TV’s greatest talker, able to conversationally seize any moment of spontaneity like no other local compere; but gravely, impeccably diplomatic, with a veteran’s sense of appropriateness.

Of course, there was the famous exception when he inadvertently insulted boxing champion Muhammad Ali at the 1979 Logies, which Newton was once again compering. He came up with the catchphrase “I like the boy”, not realising, he said, the connotation of “boy” for a black person and the controversy made its way around the world. As usual Newton survived the moment with a few jokes, Ali appreciating his host’s seeming naivety.

From the beginning of his career, Newton possessed a warm stage presence, one that enveloped and disarmed. It was there when he started, a sangfroid and a fearlessness which, considering his youth and clean-cut appearance, amazed his older colleagues, some of whom had battled for recognition for years on the comedy circuit in draughty halls and smoky clubs, learning their trade in what they called “the long grass”.

He brazenly mingled with them, absorbed their lessons unflinchingly and for years would recall their words of advice. Jack Little, the American-born announcer and one of Nine’s great voices, bold and stentorian, taught him about the grace of a friendly gesture to somebody who was new to the station.

And Australians across the decades were delighted to accept a long-term relationship with him and his wife Patti, his children Matthew and Lauren and eventually their grandchildren too, and loved the idea of Newton always being around.

But for some years now, his on-screen appearances infrequent, he had become more like the unconventional uncle, still quick with a joke or a bit of slapstick or a pratfall at family gatherings.

The public too remained fascinated by his family and the way their lives and careers developed and how they reacted to the bombshell that hit them when in 2006 Matthew faced charges of having assaulted his former girlfriend, actress Brooke Satchwell, (he was convicted of common assault, but it was subsequently overturned) in a bitter break-up row. It was something Newton said that “really hits you very deeply in your heart and soul”, but he said he was grateful for the support of so many people. But even though he was still admired and idolised, work was hard to come by.

TV’s new digital landscape, its obsession with the voyeurism and schadenfreude of so-called reality seemed to have no place for a portly chap in his 70s, that familiar idiosyncratic language, his voice mellifluous, purring and honking, and that deep resonant laugh. When Newton began his long career, we believed that TV shows came beaming into our living rooms, like visions from some powerful force, but this decades-old technical miracle has altered its shape in recent years, the one-time devout community of watchers splintering in every direction. During the period of television’s greatest expansion, we are starting to turn our backs on the slick, faceless veneer of free-to-air TV, the practised fingers of the individual taking control.

And there was no place in this new storytelling universe for one of TV’s great pioneers.

When he did pop up, occasionally on an interview program promoting one of his beloved musicals, or commenting at moments celebrating a TV or radio milestone, he still laughed at himself, the way he always had, in recent times at his elderliness and his ability to somehow survive. His agent constantly rang Foxtel boss Brian Walsh to see if it was possible Newton might replace Bill Collins in presenting old Hollywood movies – he simply never wanted to simply disappear.

Much of Newton’s comedy had always arisen from that well-developed mordant sense of self-recognition, as though he could not really believe he was still there, still working. He was never a satirist, certainly never a bitter comedian for whom humour was “a socially acceptable form of hostility and aggression” as pugnacious comic George Carlin once said. “That’s what comics do, stand the world upside down.”

Not our Bert. He lacked the rage that sometimes animated his old friend Kennedy. Newton was too tolerant of the world around him, casting only a teasing eye on things in those thousands of appearances and laughing, and causing us to smile with him, as he determined to make the most of the gifts he had, even if he was never quite sure what they were.

Paradoxically, the secret to Newton’s perennial popularity was in part his unknowability, exemplified by his sense of irony, the quality that continued to draw viewers to him over the decades, trying to catch what it was he really wanted to say. One thing is certain though: no one else worked so hard to convey authenticity and sincerity and he always did it with absolute professionalism and integrity.

“He is the ultimate realist with cunning and tenacity and a superb ability to understand the nature of the medium,” Phillip Adams once said. “He knows the effervescence of success because he’s seen it and lives with those constraints without letting it touch him. Above all Bert is the Electric Friend – he is there when you want or need him. Bert is company.”